Lifestyle

It’s not stress that’s killing us, it’s hate: Maybe mindfulness can help

There is no shortage of divisive social issues today, all competing in an increasingly crowded outrage marketplace for our attention.

With algorithms curating increasingly hateful content under the guise of “everyday news,” the ability to be curious and open to others’ perspectives has never been more critical.

As famed philosopher Michel Foucault once argued, only through tolerating dissent and understanding resistance can society change and evolve. But if tolerance rather than outrage is the metric, it feels like we are growing weaker.

What does mindfulness really mean?

Mindfulness has two components: Present-moment oriented awareness of what’s happening within and around us; and acceptance of what’s happening in our awareness. Experts believe that mindfulness offers a solution to intolerance because it promotes acceptance and subverts our knee-jerk reactions to defend our ingrained beliefs.

The increasing popularity of mindfulness has been driven by expectations that it will reduce stress. Yet, beyond quelling nerves, mindfulness equips us with the ability to embrace the distress and resentment required to examine ideas we have become comfortable dismissing — a process that requires engaging with discomfort.

Over the course of the pandemic, many of us have dipped a toe into mindfulness practices, perhaps guided by apps, self-help books or even brainwave-sensing vibrating pillows. But do most people understand that mindfulness is about engaging with uncomfortable experiences? Or is it seen as just another fad that once again puts the self at the centre of self-discovery and self-help, as some critics have suggested?

How do people understand and practice mindfulness?

As researchers of mindfulness and wisdom, we decided to look into this issue to examine whether the popular understanding of mindfulness may support the dismantling of intolerance.

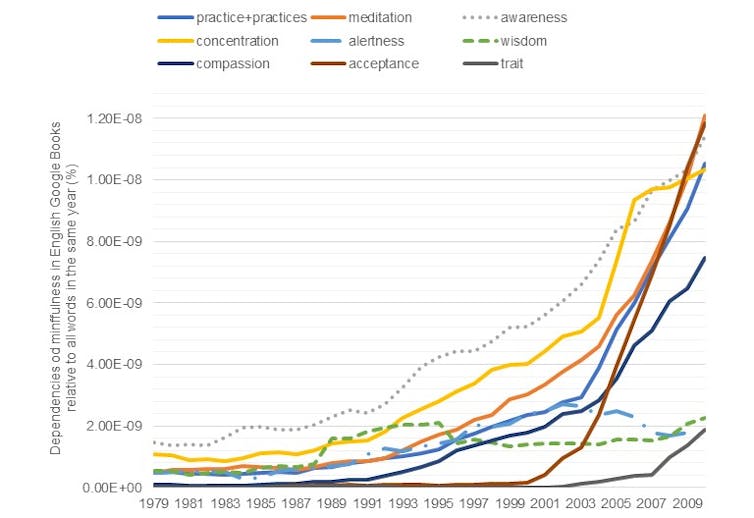

In a new report published in Clinical Psychology Review, we first determined common terms associated with mindfulness across some of the largest English language databases available today and found that public understanding of mindfulness in books, spoken and written text and websites and blogs focuses on engagement and acceptance, rather than mere stress relief. We found most people appear to understand what mindfulness means. Next, we examined whether they apply these insights in practice.

To address this question, we performed a meta-analysis, combining results from 150 studies with more than 40,000 people that investigated how people report experiencing mindfulness. Additionally, we conducted novel empirical research to test how reported mindfulness is associated with markers of engaged thought.

In theory, both the awareness and acceptance elements of mindfulness would be used together to help a person work through their challenges and daily experiences by engaging with challenging experiences in their mind. Surprisingly, that’s not what we found.

While experts claim we use both awareness and acceptance together, our meta-analysis showed that occasional mindfulness users treat awareness and acceptance as independent processes or even as opposites: people who reported greater awareness reported lower acceptance and vice versa.

And that’s not all. In a series of empirical studies we conducted, participants reporting greater acceptance were in fact reporting less engagement with their difficult issues! Instead of engaging with challenging topics by wisely reflecting on them — considering limits of their knowledge, others’ perspectives and the context of their experience — these people were either avoiding or suppressing difficult experiences.

Study after study, we saw that people scoring higher on established mindfulness measures reported lower engagement with their experiences. In practice, most people conflated acceptance with passivity or avoidance.

The unfulfilled promise of mindfulness

This is a problem. When mindfulness is understood in word but not in practice, it ceases to pave a path to wise judgment, co-operation or compassion.

Just as the ability to choose where we place our attention and how long we focus improves through awareness training, the ability to be accepting of dissenting opinions requires practice in order to create understanding instead of further marginalizing those we disagree with.

Acceptance doesn’t mean that we have to passively accept whatever cards we are dealt. It means confronting our discomfort long enough to explore what needs to be changed and being malleable enough to consider vantage points we typically ignore. Reducing stress by avoiding difficult conversations is a short-term solution that only further polarizes perspectives.

The purpose of mindfulness

Mindfulness might not provide an easy answer to the divisiveness that surrounds us, but an accurate understanding that includes the practice of acceptance may help encourage sincere discussion, generous compassion and authentic connection.

To strengthen our ability to see the present moment through multiple interpretations and from many perspectives, we may have to discover how to practice mindfulness — by applying awareness and acceptance together.

Are we willing to endure the pains of growing together or will outrage remain the more desirable status quo?

Igor Grossmann, Associate Professor of Psychology, University of Waterloo and Ellen Choi, Assistant Professor, HR Management & Organizational Behaviour, Ryerson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.