Health

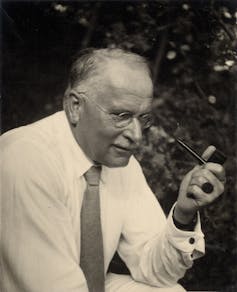

Prince Harry saga: what advice would Carl Jung give?

Prince Harry recently received attention for releasing photos of himself undergoing psychotherapy. But if Swiss psychologist Carl Jung was alive today, he’d be telling those following his story to turn the cameras on themselves.

With the Meghan and Harry saga dividing public opinion, there are plenty of lessons to learn from Jung if we are to bring some humility to this debate.

We are all children inside. You, me, Prince Harry, Prince William, Prince Charles, and the Queen. Jung once said: “The greatest burden a child must bear is the unlived life of its parents.” He proposed that our “inner child” shows how positive and negative experiences during childhood influence us later in life.

Jung argued that childhood traumas wound us and we carry those wounds into adulthood, often without any attempt to confront or overcome them. For this reason, habits and beliefs influence how we raise – or don’t raise – our own children.

In The Me You Can’t See, a documentary series about mental health, Harry recalled the trauma of losing his mother, which drove him to drink and drugs in his adult life. “I was so angry with what happened to her, and the fact that there was no justice at all,” he said. “Nothing came from that. The same people that chased her into the tunnel photographed her dying on the backseat of that car.”

Harry’s behaviour and struggles with anxiety landed him in therapy. He described how the anger he feels today takes him back to his childhood: “The clicking of cameras and the flashing of cameras makes my blood boil. It makes me angry and takes me back to what happened to my mum and my experience as a kid.”

Harry suggested that a lack of support while growing up contributed to the deterioration of his mental health as an adult, and shared his desire to break a cycle of suffering from being passed onto his children:

My father used to say to me when I was younger, he used to say to both William and I, ‘Well it was like that for me so it’s going to be like that for you.’ That doesn’t make sense. Just because you suffered doesn’t mean that your kids have to suffer. In fact, quite the opposite – if you suffered, do everything you can to make sure that whatever negative experiences you had, that you can make it right for your kids.

Jung would have some sympathy for Harry. This is not to dwell on the past for the sake of self-pity. Rather, by reflecting on our pasts we can fix ourselves and break those cycles of suffering in our families and society. We needn’t allow our suffering to bring harm to others.

Jung was not interested in blaming parents. He would not be attacking Prince Charles (and neither is Harry). Instead of solely blaming senior royals, Jung would see more wounded children.

In a previous interview with Oprah, Harry also described Charles and William as being “trapped” in an institution that they couldn’t escape if they wanted to.

No royal chooses to be born into such circumstances. Current and future generations of royalty are embroiled in a cycle that societal traditions, public demands, media rituals and cultural institutions continue to perpetuate within and beyond the monarchy.

Of course, the royals are born into immense privilege compared with most people. But no amount of privilege brings a blank slate of emotion or character to the world. We are all affected by the environment we are born into. There’s little to suggest that the realities of royal protocol are conducive to human contentment and the freedoms many of us take for granted.

Harry’s latest interview appeared a few hours after an independent inquiry concluded that journalist Martin Bashir used “deceitful behaviour” to secure his BBC Panorama interview with Princess Diana in 1995. Prince William said the BBC’s conduct “contributed significantly to her fear, paranoia and isolation”, condemning BBC bosses “who looked the other way rather than asking the tough questions”.

These findings raise moral and psychological concerns for society. As audiences, we have strong opinions about the stories, dramas, spectacles and rituals that revolve around the monarchy. These stories are told and sold to us, and our appetite does not appear to be waning.

Confronting the shadow

Jung was interested in the unconscious mind – what he called the shadow – where our least desirable traits simmer away beneath the surface, driving our personal and collective behaviours that we are least inclined to confront.

When it comes to the monarchy, Jung might suggest we take a look at ourselves, our media, our expectations, our judgments and our humility (or lack of) that is required for a more empathetic culture at every level of our society – regardless of wealth or privilege.

Jung would encourage us to challenge our tribalism and ask why we joined Team Royal or why we hate Team Harry (or vice versa). Like any family feud, there are many sides to many stories. When we ask ourselves why we feel so certain that we should take one side over the other, the answers we find are often awkward and messy.

As Jung said, confronting the shadow is never a pretty process. We are forced to look at our least desirable traits. But it is worth it. Our humility is important and our collective psychology determines what kind of society we create for ourselves and our children.![]()

Darren Kelsey, Reader in Media and Collective Psychology, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.