Canada News

Facebook vs. Australia — Canadian media could be the next target for ban

Shortly after Facebook nuked news from its platform in Australia, I spent an hour on the phone with Kevin Chan, head of public policy for Facebook, Inc., in Canada.

He told me he’s “working really hard to prevent that outcome in Canada.” In other words, if Ottawa follows Australia and tables a bill forcing tech giants to share revenue with the news business, Facebook would drop the A-bomb on Canadian journalism as well.

Chan would prefer to work out partnerships with Canadian journalism. He said Facebook gave $10 million to various news projects in the past four years. He pledged “in 2021, we’ll do quite a bit more.” But don’t put a gun to our head, he basically said, or we’ll fight back.

Render unto Caesar

I actually share many of Chan’s views. Here’s one. Last fall, the lobby group representing the news industry in Canada published a report Levelling the Digital Playing Field that contends a law similar to Australia’s would garner $620 million per year in Canada. It also says “such a pathway would make up for much of [our] revenue decrease,” implying that the web giants somehow divert advertising dollars from the news business.

This premise is false. What actually happened is that Google and Facebook have much better adapted to the digital era the business model that helped legacy media thrive in the analogue era, when print and the airwaves ruled the world.

A quote from The Washington Post Company’s 1972 annual report sums it well: “… a quality product to our audience and a quality audience to our advertisers …” Newspapers and broadcasters were attention merchants. They’ve been spectacularly upstaged by the web behemoths.

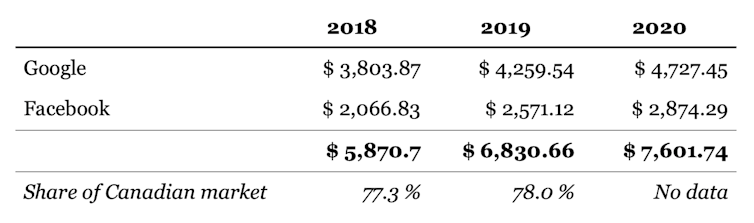

Four out of every five dollars Google earns are ad dollars. In the case of Facebook, it’s 98 per cent! In 2020, their advertising revenues represented a formidable $310 billion worldwide, including $7.6 billion in Canada alone.

Journalism is worth something

While I applaud their success, Google and more critically Facebook must in turn acknowledge some of that success rests on the shoulders of others. The attention they sell ads with is generated, in part, by news content. I asked Chan, how much. “Zero,” he answered. The value, to Facebook, is in the social link. “It is not true that news has value for Facebook.”

And this is where we diverge. In the scholarly journal About Journalism, Tristan Mattelard documented, play by play, how Facebook courted news organizations in order to attract quality content on its burgeoning platform.

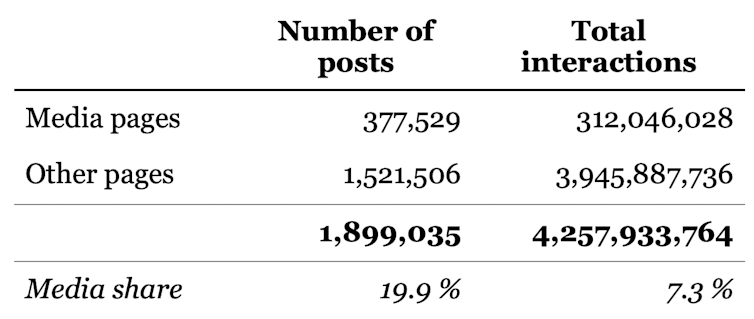

Last fall, I estimated 5.3 per cent of Facebook ad revenues between Jan. 1, 2018, and June 30, 2020, had been generated thanks to news content. I’ve repeated the exercise during the past weeks, but with a larger sample of 1.9 million posts published in 2020 on Facebook pages administered in Canada.

There’s a lot of news on Facebook. Just short of 20 per cent of all posts in my sample were from media pages, from CTV News to the Lake Cowichan Gazette. But news is Facebook’s broccoli. It drives far less interactions than the viral content usually found on the platform.

Only 7.3 per cent of the total interactions in my sample was from media pages. I apply this more reasonable proportion to Facebook’s advertising revenue in order to estimate that Mark Zuckerberg’s company made $210 million thanks to Canadian journalism in 2020.

I acknowledge this figure is an imperfect estimate. It is based on the few data Facebook allows researchers to access. But it is the least imperfect one. When asked by a La Presse journalist about it, Chan said my methodology was based on “incorrect hypotheses,” making my “conclusions erroneous.”

Chan told me Facebook doesn’t sell ads with content. More interactions don’t translate to more dollars. I understand that: if I read a Le Devoir article three times, it doesn’t bring in more advertising dollars. Facebook sells eyeballs.

Yet, those eyeballs turn to Facebook, in part, to know what goes on in their community, their province, their country. It’s in that sense that I don’t believe news has zero value to Facebook. Justin Osofsky, Facebook’s vice-president of global operations, wrote in 2013 that, “People come to Facebook to not only see and talk about what’s happening with their friends but also read news and discover what is going on in the world around them” (my emphasis).

A matter of power

Platforms feel the heat and respond by using a carrot or a stick. Google has chosen the carrot strategy and struck a deal with News Corp., Australia’s largest publisher. It is also actively working on similar partnerships with Canadian media. One Québec publisher I spoke with told me the deals could start in the summer of 2021 and translate into “millions” of dollars.

But it’s a poisoned carrot. What guarantee do we have that such partnerships will last without a legislative framework? In the small print of those deals, I saw a clause mentioning Google could pull the plug with a 90-day written notice.

There’s a tremendous imbalance in power, here. On one side, two international companies whose combined revenues in 2020 was a little more than the GDP of New Zealand. On the other, media are being read like never before by Canadians — news publishers’ websites have seen their unique visitors increase 80 per cent between 2017 and 2020 — but their revenue keeps tanking in spite of their success. They are at a disadvantage when asking Facebook to transfer some of the revenue generated by Canadian journalism.

The Australian approach aims to correct that imbalance. The clash between Canberra and the platforms is a historic struggle between public interest and private interests. The public interest is one of journalism’s core values. I always tell my journalism students: “You’ll work in various organizations, but you’ll all work for the public.”

Asking Facebook to share its revenues is not an attack on the internet. Let’s remember Tim Berners-Lee warned us in 2010 that Facebook’s “walled garden” was a recipe for abuse. It isn’t a 20th-century remedy to a 21st-century problem either. It’s legislation to support an institution working in the public interest.

Facebook’s move in Australia is an abuse of private power to counter a public body acting in the public interest. If there was one reason for Canada to follow Australia’s lead, that would be it.![]()

Jean-Hugues Roy, Professeur, École des médias, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.