Lifestyle

Swimming with whales: you must know the risks and when it’s best to keep your distance

Until recently, you had to travel to Tonga, Niue or French Polynesia for similar humpback whale encounters in Oceania. Or you could swim with other species, such as dwarf minke whales on the Great Barrier Reef. (File Photo:

Robin Canfield/Unsplash)

Three people were injured last month in separate humpback whale encounters off the Western Australia coast.

The incidents happened during snorkelling tours on Ningaloo Reef when swimmers came too close to a mother and her calf.

Swim encounters with humpback whales are relatively new in the Australian wildlife tourism portfolio. The WA tours are part of a trial that ends in 2023. A few tour options have also been available in Queensland since 2014.

But last month’s injuries have raised concerns about the safety of swimming with such giant creatures in the wild.

Close encounters

Until recently, you had to travel to Tonga, Niue or French Polynesia for similar humpback whale encounters in Oceania. Or you could swim with other species, such as dwarf minke whales on the Great Barrier Reef.

Read more:

Whale of a problem: why do humpback whales protect other species from attack?

But when we interact with wild animals there is always a risk to safety, especially in challenging environments such as open water.

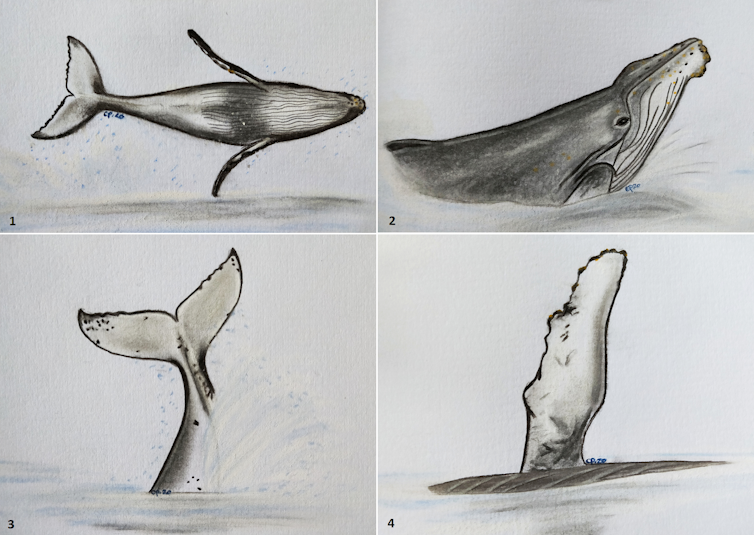

Whales, like other wildlife, may behave unpredictably. Active surface behaviours such as breaching, tail and fin slaps present a significant risk for swimmers and whale watchers.

Chantal Denise Pagel, Author provided

In one of the WA encounters, the nursing female was reported to display pectoral fin and tail slaps. These are potentially threatening due to the size (up to 16 metres long) and power of humpback whales.

These behaviours are frequently observed in social interactions between humpback whales and can present a severe risk of injury to anyone close by, with potentially life-threatening results.

A recent study of the impacts of swimmer presence on humpback whales off Réunion Island (on Madagascar’s east coast in the Indian Ocean) confirmed a high occurrence of aggressive and/or defensive whale behaviour.

The researchers observed flipper and tail fluke swipes and thrashes – sudden movements of a whale’s extremities – especially in mother-and-calf pairs.

Flickr/Michael Dawes, CC BY-NC

Keep your distance

While the reasons for the Australian incidents are still unclear, a possible explanation could be that the swimming groups approached the whales too closely and ignored the signs the whales did not welcome visitors.

Maintaining a safe distance should be required of any tourists interested in seeing or getting close to unpredictable wildlife, especially in unfamiliar environments.

We cannot expect tourists, who are often first-time whale swim participants, to be able to read and interpret whale behaviour. So it is vital that crew members are skilled and experienced and can end an encounter if it needs to be.

Knowledgeable in-water guides are indispensable in commercial swim-with-whales programs. Yet this is often not a requirement by organisations issuing licenses for such activities.

For example, permits in New Zealand require “knowledgeable operators and staff”, but there is no requirement to have guides in the water during the encounter. People interested in swim-with-whale encounters should choose tour companies that provide in-water guides who join them in their adventure.

We should also question whether interactions with female whales caring for newborn calves should be allowed. Best-practice guidelines advise against interactions where calves are present.

Recent research in the popular whale-swim destination Tonga showed mother-and-calf pairs avoid about one-third of tour vessel approaches by diving for longer periods.

Yet surface resting times are critical for calves. Any decrease in time spent resting for mother-and-calf pairs can affect a calf’s growth rate, overall fitness and chances of survival.

Similar observations were made in Réunion. Three out of four (74%) mother-calf-pairs changed their behaviour to avoid swimmers.

Safety first: for whales and swimmers

The Pacific Whale Foundation is undertaking a study to assess the impact of swimming with humpback whales in Hervey Bay, Queensland, Australia.

This research is to monitor the behaviour of humpback whales, providing critical insights into whether tourism activities add stress to this recovering population.

Read more:

COVID-19, Africa’s conservation and trophy hunting dilemma

But research into the suitability of wildlife species used for commercial tourism operations and their health and safety provisions still lacks fundamental depth.

In highly interactive tourism activities such as swim-with-wildlife programmes, tourists should receive education about the risks involved in these “bucket list” experiences. This should include information on animal behaviour and the potential consequences for swimmers.

Furthermore, training tour operators to identify behaviours that may indicate disturbance or have the potential to be harmful to clients is an important additional step towards safer interactions.![]()

Flickr/Grant Matthews, CC BY-NC-ND

Chantal Denise Pagel, Doctoral student | Marine Wildlife Tourism Professional, Auckland University of Technology; Mark Orams, Acting Dean, Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, and Michael Lueck, Professor of Tourism, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.