Canada News

How some OECD countries helped control COVID-19 in long-term care homes

At the time our report was finalized, the number of reported COVID-19 deaths among long-term care residents varied substantially around the world, from 28 in Australia to 30,000 in the United States, and more than 10,000 in each of France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. (File Photo: Steven HWG/Unsplash)

People living in long-term care facilities and seniors’ residences have had their lives disproportionately affected by measures taken to stem the spread of COVID-19. In addition to things like social distancing and hand-washing, policies in Canada and other countries have included quarantining in individual rooms, and limited or no access to family members, who are often caregivers as well.

The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) is dedicated to collecting and providing health data on our health systems, and supporting comparable analysis of their performance. After the first three months of the COVID-19 experience, we have reviewed how different countries managed COVID-19 in long-term care settings.

Restrictive measures were a response to a terrible threat to public health. It is important to recall that in the early spring modelling, the COVID-19 epidemic in Canada was tracking the same path as in Italy. All levels of government in Canada have taken extraordinary measures to avoid the experience of overwhelming our hospital systems with COVID-19 patients.

Impact of COVID-19 in long-term care

While Canada has been largely successful in managing the impact on hospitals, the same cannot be said about long-term care facilities; more than 80 per cent of COVID-19 deaths in Canada have been in long-term care.

On June 25, CIHI released an international analysis that shows how Canada compares to 16 other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in its COVID-19 response in long-term care. The analysis focuses on three areas of comparison: cases and deaths, baseline health system characteristics and policy response.

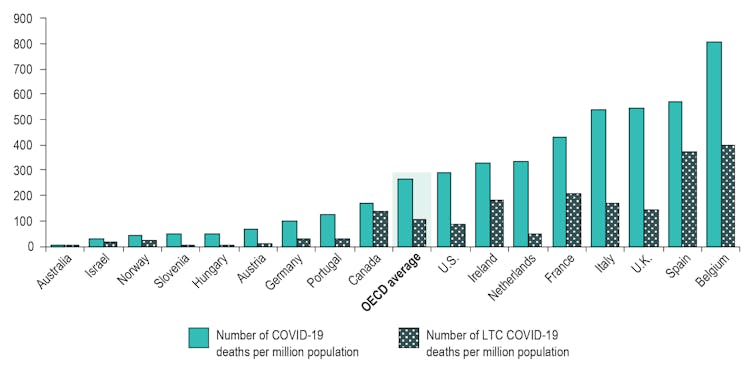

At the time our report was finalized, the number of reported COVID-19 deaths among long-term care residents varied substantially around the world, from 28 in Australia to 30,000 in the United States, and more than 10,000 in each of France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom.

Canada and the OECD

While Canada’s overall COVID-19 death rate is relatively low compared to other OECD countries (176 deaths per million in Canada versus the OECD average of 266 deaths per million), it has among the highest proportion of deaths occurring in long-term care. More than 5,000 long-term care residents have died. In other words, our long-term care homes are driving COVID-19-related deaths in Canada.

While the numbers and statistics from this report are difficult to read, there are lessons we can take from it. Canada can benefit from a comparative look at other countries. Australia, Austria, Netherlands, Hungary and Slovenia implemented mandatory prevention measures in long-term care homes at the same time as their stay-at-home orders and public closures, and had fewer COVID-19 infections and deaths in long-term care.

(CIHI), Author provided

Many control measures had an impact. These included broad COVID-19 testing and tracing in homes, isolation wards to manage clusters, additional supports for workers such as surge staffing, specialized teams and personal protective equipment.

The report also showed that countries with centralized regulation and organization of long-term care facilities generally had lower COVID-19 cases and deaths. However, more information is needed in Canada to evaluate how organizational models, among other factors, affect outcomes.

Local measures

We can also look at additional local measures within Canada that have been shown to be effective.

For example, in Kingston, Ont., a combination of early inspections of home infection control practices, the availability of health practitioners to follow up on questions about practices, as well as a strong partnership between long-term care, public health and the local hospital has resulted in no long-term care infections in and around the Kingston area to date.

Meanwhile, British Columbia has so far been successful in controlling the spread of facility outbreaks by making all long-term care staff public employees for six months, providing workers with comparative pay, full-time work and sick leave benefits. This allowed staff to take time off work if they were exposed to COVID-19, dedicate their time to simply one facility, as well as streamline public health information.

Understanding the supply of personal protective equipment, the number of beds and how they are configured in homes would have helped with development of plans for isolating residents who became infected. Data on staffing levels, including how many work in multiple homes would have helped to identify gaps across the country. Having earlier and more comprehensive testing of long-term care staff and residents would have improved data about infection rates in residents and staff, which are both key to identifying and containing outbreaks.

The importance of data

In Canada, we do have rich clinical data for long-term care residents. This allows homes to plan their care, assess how it’s working and monitor risk (such as risk of pressure ulcers or falls). This same data supports and underpins publicly reported quality measures, including falls, worsened depression or worsened pain. Expanding long-term care data to include all provinces would enable complete reporting of quality of care measures. Reporting on a standardized set of pan-Canadian indicators can help improve quality of care for all people living in long-term care.

Ultimately, we know good data leads to good decisions. With the data we have, and the opportunity to start collecting and using more information, better decisions are possible. Thousands of people across the country — from all walks of life — have made significant sacrifices to protect others. When we ask them to do so again, we owe them the best possible explanation of why it’s necessary.

The more we know, the better we can do.![]()

David O’Toole, President, CEO Canadian Institute for Heath Information (CIHI), Queen’s University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.