Canada News

How Wet’suwet’en butterflies offer lessons in resilience and resistance

FILE: Photos from the blockade on CN Rail near Pioneer Village, where land defenders and protestors gathered for a direct action on the 2nd largest rail classification yard in Canada. (Photo by Jason Hargrove/Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en peoples collaborated in 1987 to challenge the British Columbia government and legally establish title to their ancestral territories. That landmark case, known as the Delgamuukw case, confirmed hereditary governance and title over traditional lands. It has been cited repeatedly in recent weeks in the news.

That same year, Mi’kmaq artist Mike MacDonald created a five-monitor video installation called Electronic Totem. These art videos present scenes of sustenance from Gitxsan lands, located in northern British Columbia: berry picking, fishing and waterways, as well as language and song that document the Gitxsan relationships with their territory.

Through the late 1980s, MacDonald continued creating his work in conversation with elders by documenting oral histories that became evidentiary testimony presented in court for the land title case, and also in a project for the tribal council to build a record of traditional medicines and their uses in the Gitxsan language.

While documenting an area threatened by clear-cut logging on a mountain range near Kitwanga, B.C., MacDonald noticed the widespread presence of butterflies. He took photos of the pollinators and showed them to an elder who explained the connections between butterflies, medicine plants and healing.

MacDonald witnessed how resource extraction threatens Indigenous communities and also the pollinators, and began planting medicine and butterfly gardens across the country, creating places that called for contemplation of human connection with all living things.

MacDonald’s gardens restore the land by reintroducing native plants to altered sites. His work highlights not only the fact that land cannot be separated from human lives, economies, industries and actions, but also that it is resilient.

We recently launched Finding Flowers, a cross-Canada project that explores the connection of people, land and pollinators through ecology, art and teaching. This interdisciplinary research involves a variety of partners, including Indigenous artists, ecologists, students and art galleries to co-produce knowledge about these relationships.

A repeating history

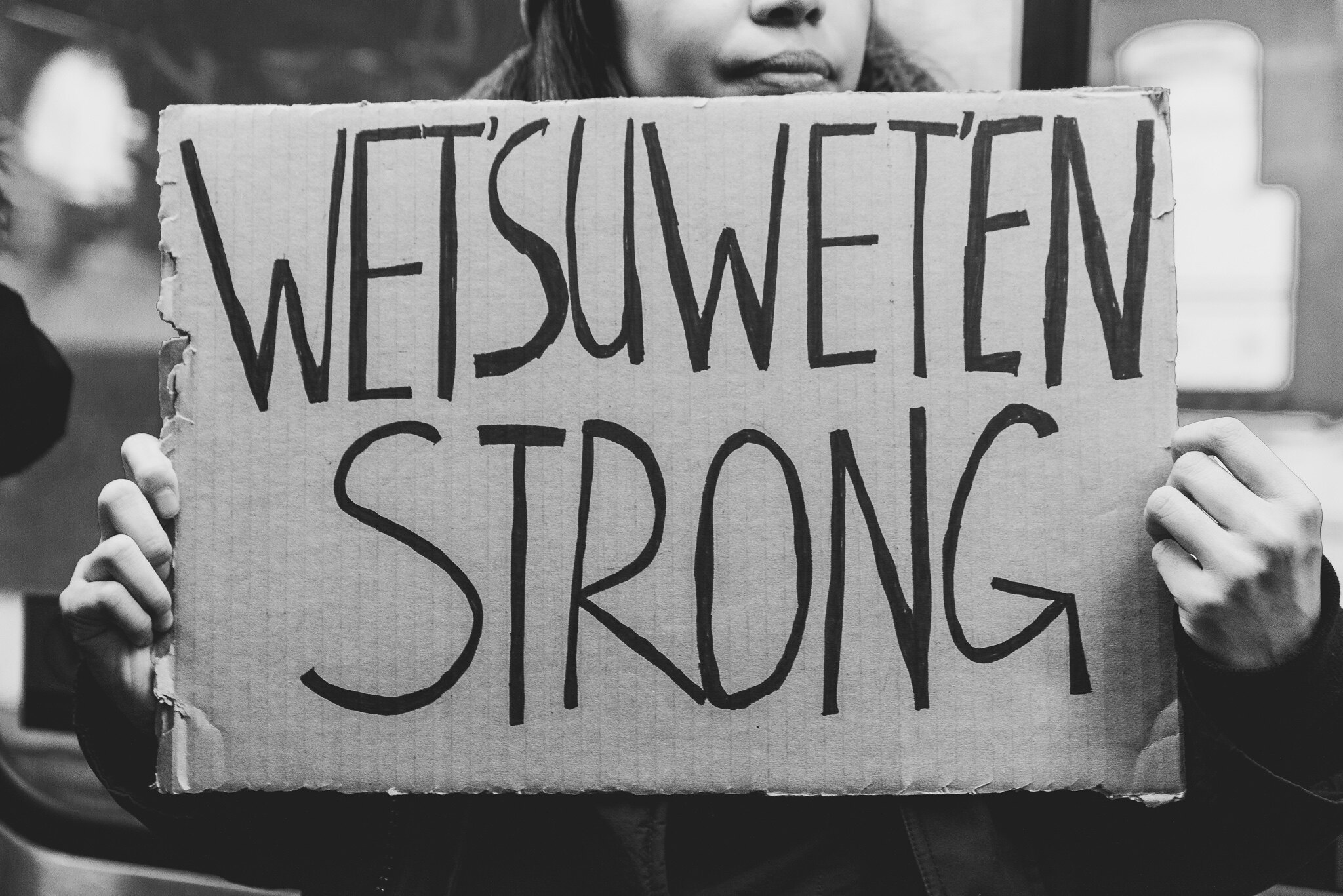

That these pollinator gardens across the country emerged from Indigenous resistance on Wet’suwet’en territory is so relevant to the contested development of the Coastal GasLink LNG pipeline through the same territory.

Despite the passing of 30 years between the logging and today’s pipeline protests, there are similarities. Conflict in this territory resonates across larger landscapes and brings to light broader challenges with respect to Indigenous rights and environmental protection in a country built on resource extraction and genocide.

Since MacDonald’s observations in the late 1980s, the decline of pollinators has become a mainstream environmental issue with intense public interest. Dramatic losses of butterfly and bee species have been documented in Canada and have raised concerns about potential economic and ecological impacts of losing the ecosystem services these insects provide.

Documented threats to pollinators in Canada include climate change, pesticide use, habitat loss, and disease introduction. The threats differ across species and across regions, but a common root cause is growth of various extractive industries, industrial farming and urbanization, all at the expense of nature.

While extensive media coverage, public concern, political will and resources have been directed to conserving bees and other pollinators, the reality remains that insect species continue to decline.

It is becoming painstakingly clear that addressing core issues with respect to Indigenous land stewardship, resource extraction and corporate interests remain critical to addressing large-scale environmental concerns such pollinator loss in Canada and beyond.

Butterflies and medicine plants

TC Energy’s attempts to build the $4.7-billion Coastal GasLink pipeline in unceded Wet’suwet’en territories is another example of settler-colonial violence and inadequate consultation processes that uphold resource extraction.

Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs have not given consent to the pipeline development. Their demands align with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action, and they have expressed concerns about the environmental, legal and spiritual impacts of this project trespassing their territories, particularly in regards to their stewardship of fresh drinking water and healthy salmon populations.

Past and recent lessons from the Wet’suwet’en territory highlight what Canadians have had to and will continue to grapple with: the desire to conserve wildlife may come at the expense of short-term economic gain. That requires a deep and reflective approach to our relationship with land and the Indigenous peoples who have stewarded these territories since time immemorial.

MacDonald’s medicine and butterfly gardens are sites of Indigenous ecological, cultural and spiritual knowledge. They are also spaces that call for changing approaches to resource extraction and reflecting on relationships with land.

By restoring habitats with native plant medicines, for both people and wildlife, MacDonald restored land for deep contemplation, resilience and hope. MacDonald’s garden artworks show us the repeating story of the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en assertions of their ancestral territories, reminding us of ways to contend with these challenging times and how listening can give us a richer, deeper understanding of the interconnections between land, water and all living beings.

The world is beginning to better understand that the core of extractive industries are tied to deep political and economic conflicts related to the settler-colonial present and a shared colonial history. Conservationists and governments are increasingly citing the need for Indigenous knowledge and engagement in the co-management of land, and they are advocating for Indigenous-led protected areas as critical solutions towards mitigating the biodiversity crisis and climate change.

Canadians need to connect the dots of today’s political actions, and know that if they are going to address these crises, they need to learn about and reconcile with our colonial history and present, and support Indigenous communities’ self determination.

———

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Disclosure information is available on the original site. Read the original article:

https://theconversation.com/how-wetsuweten-butterflies-offer-lessons