Entertainment

Climate documentaries aim to create change, not preach to the converted

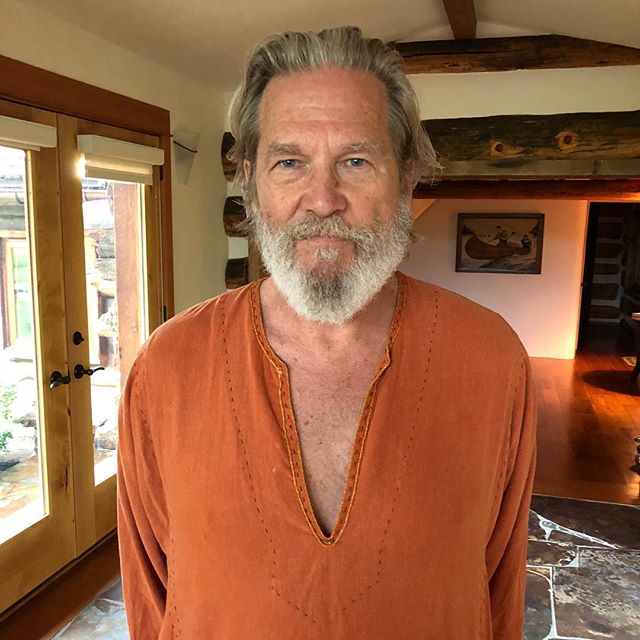

Bridges wanted “Living in the Future’s Past” to take a fresh approach. When he first discussed collaborating with director Susan Kucera, he said he felt there were enough climate movies that pointed fingers and told audiences they were in dire straits. (File Photo: @thejeffbridges/Instagram)

VANCOUVER — Academy Award-winning actor Jeff Bridges wanted to avoid making a climate change documentary that only preached to the converted — he wanted to reach and speak to people who didn’t already care about the issue.

That’s why “Living in the Future’s Past,” produced and narrated by Bridges, deliberately avoids heaping guilt upon viewers or hammering them with warnings of impending doom, the “Big Lebowski” star said.

“I think the fear makes you throw up your hands and feel like it’s too late, or think it’s going to trickle down from the government,” Bridges, 69, said in an interview.

“But I don’t think we can wait for the government to be enlightened with what our scientists are telling us. I think it’s got to trickle up, if it’s trickling anywhere. I think we all have to take action.”

The film is part of a rising tide of documentaries that aim to wake up viewers to the realities of climate change. But as governments, companies and individuals remain reluctant to act, it’s fair to question how much of an impact movies can have.

Bridges wanted “Living in the Future’s Past” to take a fresh approach. When he first discussed collaborating with director Susan Kucera, he said he felt there were enough climate movies that pointed fingers and told audiences they were in dire straits.

The pair discovered they were interested in why humans as a species were responding the way they were to climate change. As a result, the film interrogates how evolution, history and psychology have shaped our reaction to the unfolding crisis.

Bridges likes to use a metaphor inspired by one of his heroes, Buckminster Fuller, who invented a small rudder called a trim tab that helps turn a larger rudder on a ship. The tab symbolizes how the individual is connected to society, he said.

“We all can make a huge difference, just like that little rudder on the big rudder,” Bridges said. “We can all do it in different ways. I’m in the movie business, so I make movies.”

The film showcases a wide range of prominent scientists and authors. Yet one of the most refreshing voices is former Republican congressman Bob Inglis, who argues caring about the environment is not at odds with a conservative or religious identity.

“He has this idea that if you’re going to go to a group of people who are self-identified in one way, who better to talk to that group than someone from that group?” said Kucera. “We’re still kind of tribal that way, and so that’s what he does.”

The beautifully shot film will screen this week as part of Elements Film Festival at Vancouver’s Telus World of Science. Also screening are local films including “Coal Valley” and “Plastic Beach” and international features such as “Queen Without Land.”

Carol Linnitt, who co-founded online news outlet The Narwhal and directed “Coal Valley,” said documentaries allow storytellers to delve deeper into an issue and often the outlet’s films reach an audience far beyond its regular readership.

“We live in a fast-paced, attention-driven world these days.

Often, the dry written word sitting static on a page may not be what’s going to do it for a lot of people,” she said.

Of course, it also matters who sees these films. Bridges said he was excited to be working on a curriculum that would allow his movie to be taught in schools, where it would encourage kids to take action and use their imaginations to solve the problem.

Keith Scholey, series producer of the lush Netflix nature documentary “Our Planet,” said the filmmakers created a website, OurPlanet.com, to give viewers more details about solutions, and they’re also screening the show for global decision makers.

“So far, we have been able to present ‘Our Planet’ to the World Economic Forum in Davos and next week will do the same to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. We think we have already started to bring about change,” he said.

Still, humans are so notoriously apathetic about climate change that one environmental psychologist has catalogued all the reasons people don’t take action. Robert Gifford of the University of Victoria describes them as the “dragons of inaction.”

“The less polite word might be excuses or justifications,” he deadpanned.

He said common “dragons” include: “I’m only one person. Why should I do anything if my efforts don’t make a difference?” and “It’s the government’s job, not mine.”

Environmental films are more likely to make a difference if they are quiet and serious, such as Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth,” as opposed to over-the-top Hollywood fare that will just make viewers roll their eyes, Gifford said.

The most important factor in persuading people to care about climate change, however, is to demonstrate how it intersects with an issue they care about, such as their health, children or local community, he added.

“There is no magic message for everybody.”