News

Ex Pennsylvania governor joins safe injection site effort

“You can commit a lesser harm to prevent a greater harm.” (File Photo: By Science History Institute/Wikimedia coomons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

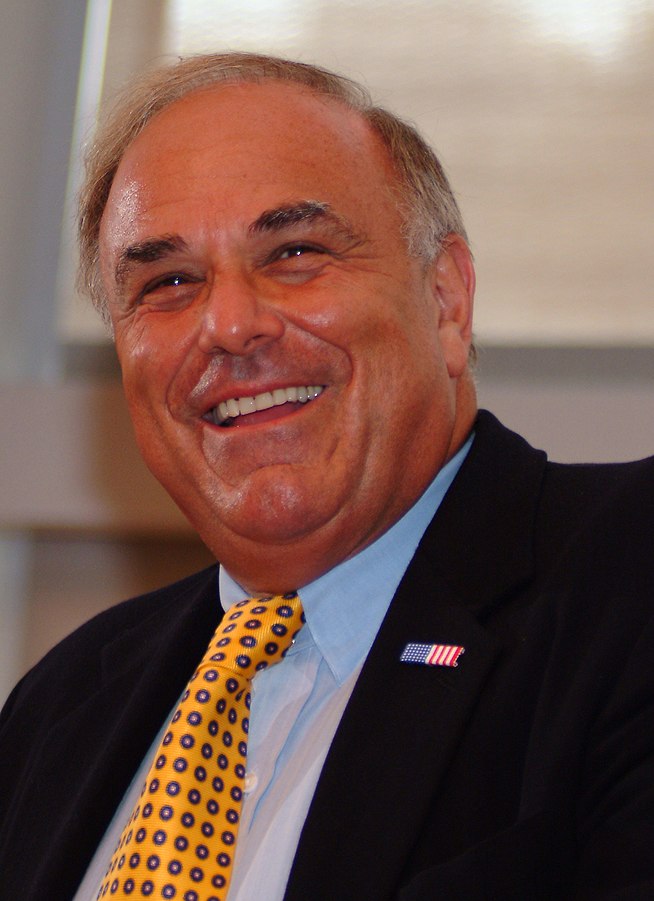

PHILADELPHIA — Former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell has joined the effort to open Philadelphia’s and possibly the nation’s first supervised drug injection site— saying Wednesday that he would support the effort even if it meant facing federal charges.

The 74-year-old Rendell joined the board of the non-profit Safehouse, which is raising money to open a safe injection site— a place where people can use drugs under medical supervision including overdose prevention— despite federal and state laws that prohibit them. Rendell bucked similar regulations when he was Philadelphia mayor in the 1990s and officially sanctioned the city’s first needle exchange program, inviting the then-state attorney general to arrest him at City Hall.

Rendell said Wednesday that he is still willing to go to prison.

“If I thought for a minute that safe injection sites would create new addicts, I wouldn’t be a part of it. I see the ability to save lives and get people who are addicts exposed to treatment,” he said. “Having me involved, I think it reduces the chances that there will be arrests. It’s not likely, but it’s somewhat possible they will come and arrest me.”

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney and other city officials announced in January that they would support a private entity operating and funding safe injection sites. Philadelphia has the highest opioid death rate of any large U.S. city, with more than 1,200 fatal overdoses in 2017.

Rendell said if enough money can be raised, it’s possible that Safehouse could open the city’s first supervised injection site by the end of the year.

Rendell’s statements come just days after California Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed legislation that would have given San Francisco some legal cover to open the nation’s first injection site as part of a pilot program. The bill would have protected workers and participants from state prosecution for illegal narcotics, but not from federal charges.

Deputy U.S. Attorney Rod Rosenstein told public radio station WHYY in August that the federal government would take swift and aggressive legal action if cities open sites. Rosenstein said he “wouldn’t speculate” on what the enforcement would look like or who might be arrested, but he said federal officials have their eyes on Philadelphia.

The Pennsylvania attorney general’s office has said that state and federal laws would need to change for the injection sites “to be considered lawful.”

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, however, had a different view. He said he will decline to prosecute workers or volunteer medical students who set up “a responsibly run harm reduction centre,” saying there is a justification he could see under the doctrine of self-defence.

As a young criminal defence attorney, Krasner was retained to defend Prevention Point, the city’s first sanctioned needle exchange, if the state or federal authorities decided to arrest people.

“You can commit a lesser harm to prevent a greater harm,” Krasner said. “We are literally losing four lives a day (to overdoses) in Philadelphia. The harm we are talking about here is much less serious. It is my opinion as the elected District Attorney that this conduct is flat out justified.”

There are law enforcement officials who oppose the sites as sanctioning illegal drug use. Philadelphia Police Commissioner Richard Ross has made clear that he is not sold on the idea of the sites but has said previously he would keep an open mind.

Members of the treatment and recovery community have largely shifted to be in favour of the sites, which have operated in several European countries, Australia andCanada for years, because they often offer people counselling and options for treatment if they choose it.

Peter Schorr, the CEO of Retreat Premier Addiction Treatment Centers, runs two treatment centres in Florida and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, about 80 miles (128 kilometres) west of Philadelphia.

“You aren’t putting an ad out saying please come try drugs here,” he said. “The number one killer of 18- to 24 year-olds is now overdoses. We get the opportunity to talk to them about going into a treatment facility. I think it’s something we need to do.”