American News

Mayor Keisha? Ethnic names no obstacle for black candidates

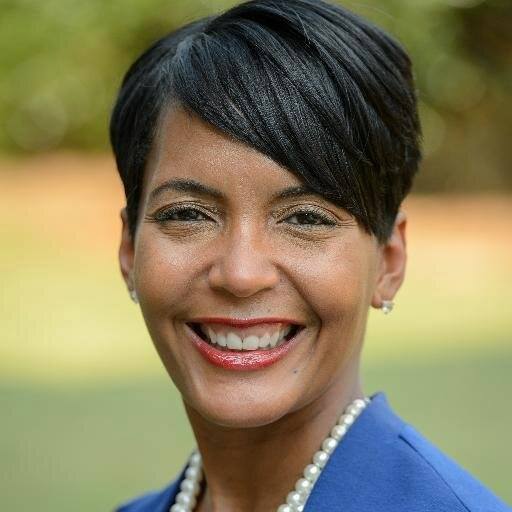

FILE: Keisha Lance Bottoms (Photo: Keisha Lance Bottoms/Facebook)

Atlanta’s next mayor could be a black woman named Keisha — a prospect that thrills Diamond Harris.

The 28-year-old graphic designer exulted Wednesday on her Facebook page: “Keisha, Keisha, Keisha! I just want a mayor name Keisha.”

Harris, a native of Saginaw, Michigan who moved to Atlanta last year, cast her ballot Tuesday for city councilwoman Keisha Lance Bottoms, who will face fellow councilwoman Mary Norwood in a Dec. 5 runoff election.

“Just having a mayor whose name isn’t the standard name you would find on a coffee mug . I don’t know what could be better!” Harris said in a phone interview. “It’s kind of like when (Barack) Obama became president.”

A campaign once fixated on the possibility of Atlanta electing a white mayor for the first time in decades has suddenly shifted to the notion that the city could end up with “Mayor Keisha” — adding Bottoms to a growing list of politicians whose ethnic-sounding names haven’t hindered them from winning elected office.

Ethnic-sounding names have long been considered an obstacle, particularly when applying for jobs or college admissions. The 1970s “black is beautiful” movement led to a boom in Afrocentric names, and many of those children are now adults working across all facets of American society, including politics.

“By asserting their identity and using their given names, they’re asking people to take them as they are,” said Emory University political scientist Andra Gillespie. “In a city like Atlanta, with a large African-American population and a long history of African-American leadership, that’s just not a liability.”

A study published in January 2016 in the journal “Evolution and Human Behavior” showed that men whose names were viewed as stereotypically black are more likely than their non-stereotypically named counterparts to be imagined as physically large, dangerous and violent.

Lately, such bias seems to be less of an issue at the ballot box.

Voters in recent cycles have elected Mayor Chokwe Lumumba, 34, in Jackson, Mississippi, Mayor Ras Baraka, 47, in Newark, and U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris, 53, in California. An upcoming runoff between LaToya Cantrell and Desiree Charbonnet will give New Orleans its first-ever black woman mayor.

These names are a striking contrast from those of blacks who enjoyed political success a generation ago.

On Nov. 7, 1967, Carl Stokes was elected in Cleveland as the first black mayor of a major U.S. city. The helms of Los Angeles, Chicago, New York and the District of Columbia went in ensuing years to Tom Bradley, Harold Washington, David Dinkins and Walter Washington.

Among current members of the Congressional Black Caucus, there is a mix of mainstream names (John, James, Maxine, Eleanor) and ethnically flavoured names (Hakeem, Andre, Kamala).

Such names carry less of a stigma with black voters — especially the loyal Democratic voting bloc of black women — because they are likely to have friends and family with such names, said political strategist Symone Sanders. And, she added, racial tension currently permeating the U.S. political climate may have encouraged candidates of colour to drop any hang-ups about whether their names would get in the way.

“It has broken down what people once thought was socially acceptable,” Sanders said. “Now Keisha, Kamala and Kiki don’t care; they know they have something to offer. I believe we’re going to see more of that.”

Only three cities — Atlanta, Newark and Washington — have continuously kept black leadership in City Hall. If elected in Atlanta, Bottoms could maintain a streak that’s held since Maynard Jackson first won office in 1973. Jackson was succeeded by black mayors named Andrew Young, Bill Campbell and the city’s first woman mayor, Shirley Franklin.

Bottoms landed in the runoff by besting a slew of black candidates, including a few with names like Ceasar and Kwanza. Should she win, Bottoms would succeed the city’s current mayor, Kasim Reed.

Bottoms deployed the hashtag #IStandWithKeisha on social media, with mostly black voters voicing their issues of concern and identifying themselves by name alongside hers. Those responding to that call included television personality La La Anthony, and singer Tameka “Tiny” Harris.

One factor in the increased number of black candidates with culturally identifiable monikers, Gillespie said, is parents of the ’70s who gave their children Afrocentric names or created self-styled names for them.

“Even Clarence Thomas has a son named Jamal,” Gillespie noted, referring to the lone black justice on the Supreme Court.

During his historic campaign, Obama frequently called himself “the skinny guy with the funny name,” a nod to the idea that his name could be a political impediment. In 2008, he told the crowd at a political dinner that his middle name, Hussein, came from “somebody who obviously didn’t think I’d ever run for president.”

In claiming her shared victory late into election night, Bottoms seemed to be having fun with her name, taking the stage with her family to rapper Drake’s hit song, “Started From the Bottom.”

Tishaura Jones certainly can relate. The 45-year-old city treasurer of St. Louis, who narrowly lost this spring’s mayoral contest, said she never saw her name as an obstacle to running for office.

Her father, Virvus, who served as city comptroller, almost named her Olatunji — a Nigerian name that means, “wealth woke up again.”

“Can you imagine ‘Olatunji Jones’ on the ballot?” Jones laughed. “It’s King’s dream realized … People are being judged on the content of their character, not the black sounding-ness of their name.”