MANILA, Philippines — Five years after gunmen flagged down a convoy of cars in a southern Philippine province and massacred all 58 occupants, including scores of journalists, the body count continues to rise.

Just days before the Philippines marked Sunday’s anniversary of the carnage with prayers and calls to end impunity, another potential witness in the ongoing trial against the politically powerful suspects was gunned down.

Here are some questions and answers about this case — the largest criminal trial in the Philippines since World War II and a litmus test for President Benigno Aquino III, a reformist who has vowed to punish the perpetrators.

Q: WHY IS THE CASE TAKING SO LONG?

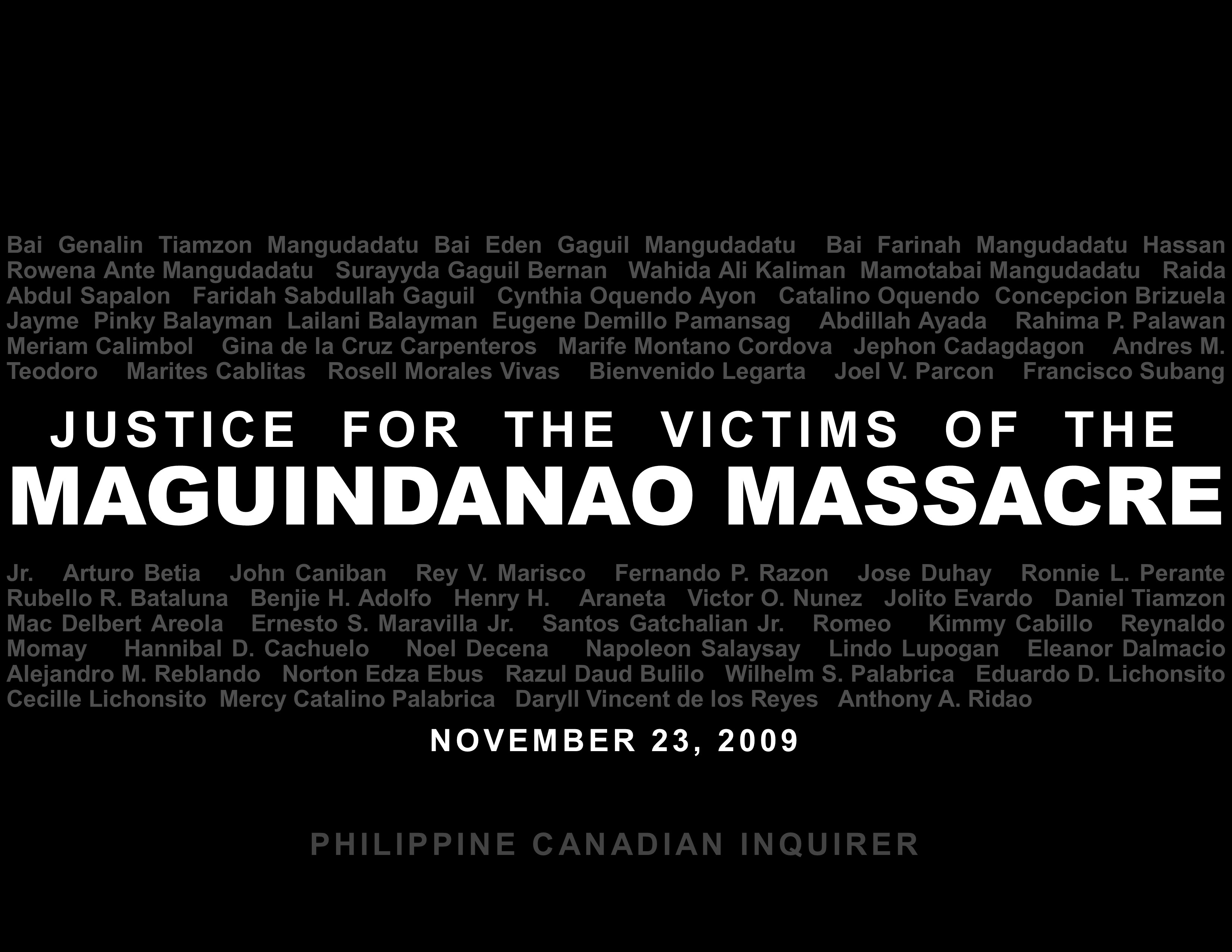

A: Justice Secretary Leila de Lima says the case has been slow because of its sheer size and complexity. Nearly 200 people have been charged for the deaths of the 58 victims, including 32 journalists and their staff in the largest mass killing of media workers in the world.

The principal suspects are members of the Ampatuan clan, who had ruled Maguindanao province for decades. According to the prosecutors, their motive was to prevent rivals from challenging them in elections. Most of the victims were the Ampatuans’ political opponents and the journalists who accompanied them on their way to register their candidacy when they were stopped and killed.

The Ampatuans have denied the charges against them.

Prosecutors have presented 147 witnesses, while the defence has begun calling 300 more. Recent proceedings, which are held two to three times a week, have been tied up in bail hearings.

At the start of the trial in September 2010, a prominent senator, Joker Arroyo, said that the volume of the case and the intense legal battle could make it last 200 years. He exaggerated to make a point — de Lima says she expects some of the principal suspects to be convicted before Aquino’s term ends in mid-2016.

As the trial drags on, however, families of the victims are increasingly frustrated. Complicating the picture is chronic insecurity in the southern region, where gunmen on the loose scare away witnesses. According to prosecutors, at least eight witnesses, potential witnesses and their relatives have been killed in an attempt to suppress testimony.

The latest victims were Dennis Sakal and Sukarno Butch Saudagal. They had previously worked for the Ampatuans but agreed to testify against them, said Maguindanao Gov. Esmael Mangudadatu, whose wife, three sisters and several political supporters died in the massacre.

The two men were riding a motorcycle when gunmen attacked them last Tuesday, killing Sakal and wounding Saudagal. Police have not identified the attackers.

“Each killing of a witness creates a fresh injustice, while reducing the chances of justice being served for the families of the victims of this horrific massacre,” said Hazel Galang-Folli of Amnesty International in the Philippines. “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

Human Rights Watch says the trial is in “effective judicial limbo” and the continuing attacks on witnesses “a shameful exemplar of impunity in the Philippines.”

Q: WHAT HAS THE GOVERNMENT DONE TO SPEED UP THE TRIAL?

A: Because of backlogs and an inadequate number of judges and prosecutors, the average case in the Philippines can take a decade to be resolved. To avoid this, the Supreme Court has created a special court just for the massacre. It assigned two judges to help the presiding judge.

The special trial court has also encouraged prosecutors to submit witnesses’ statements in writing to save time. Many, however, continue to call witnesses to the stand because they want to avoid additional paperwork.

The government has strengthened its witness protection program, but in a country with rampant extrajudicial killings, testifying against the rich and powerful means taking big chances. For example, Esmail Amil Enog had testified that he drove dozens of gunmen to the site of the massacre from the residence of one of the suspects. A year later, in 2012, he was shot dead and his body chopped to pieces. He refused the witness protection, saying it was too difficult for him to live in hiding, according to justice officials.

There’s also suspicion that the key suspects would prefer a court ruling after Aquino’s term ends in 2016, hoping for a more favourable outcome. The Ampatuans were political allies of Aquino’s predecessor, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who has been detained on vote-rigging charges.

Q: HOW HAS THE SITUATION ON THE GROUND CHANGED SINCE THE MASSACRE?

A: A volatile mix of unlicensed firearms, private armies and guns-for-hire, Muslim insurgent groups, weak law enforcement and a violent history of clan wars has endured beyond the massacre.

Out of the 197 massacre suspects, at least 84 mostly militiamen who were loyal to the Ampatuans remain at large and have reportedly joined other armed groups.

Still, the government considers the arrests of the Ampatuans and their removal from power a change for the better. Some Ampatuan relatives still hold local posts, but are “more subdued and quiet,” said regional military spokesman Col. Dickson Hermoso.

Maguindanao has shifted back to democracy, although the province of more than a million people remains under a state of emergency that was imposed following the massacre, to ensure “nobody can go walking around with an unauthorized gun and threatening everyone,” said Mangudadatu, the provincial governor.

That massacre “will never happen again,” Mangudadatu said.