WASHINGTON — While in office, former President George H. W. Bush once plaintively asked, “What is it about August?”

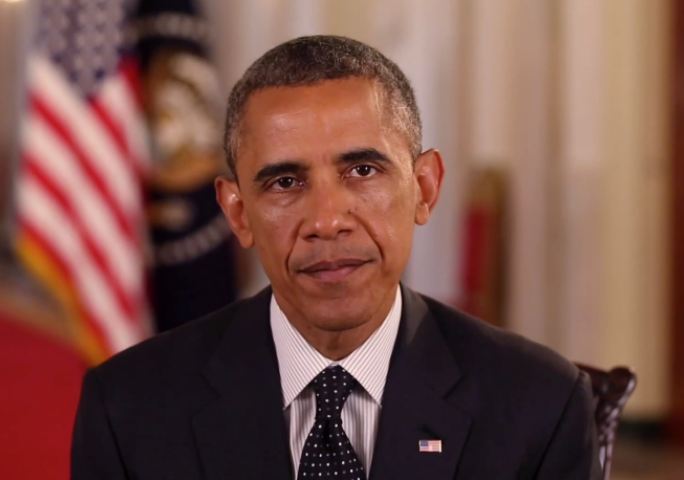

Indeed, this sultry month usually associated with the doldrums of summer has burdened modern presidents with personal, domestic or international crises. And for President Barack Obama, who returned to Washington Sunday from a two-week Martha’s Vineyard vacation, what remains of the August calendar looks perhaps more daunting than when he left.

Islamic militants personalized their fight in Iraq and Syria by executing American journalist James Foley. Russia escalated tensions in Europe by moving artillery and troops on the Ukrainian border and pushing a convoy into the former Soviet republic without Kiev’s approval. And a Chinese fighter jet provocatively buzzed a Navy plane in international air space.

His arrival back in the nation’s capital came with one positive note – Sunday’s release of an American freelance journalist who had been held hostage by al-Qaida affiliates in Syria.

Still, Obama faces his own self-imposed end-of-summer deadline for how to sidestep Congress on changes to U.S. immigration policies. And while racial tensions in Ferguson, Missouri, over the police killing of an unarmed young black man have subsided, the St. Louis suburb remains under the White House’s wary gaze. Amid all that, he’ll give a speech to the American Legion in Charlotte, North Carolina, on Tuesday and raise money for Democrats in New York and Rhode Island on Friday.

He certainly is not the first commander in chief to find August so vexing.

President George H.W. Bush had to respond to Saddam Hussein’s August 1990 invasion of Kuwait. Bill Clinton admitted to an inappropriate relationship with Monica Lewinski in August of 1998 and days later ordered air strikes against terrorist bases in Afghanistan in retaliation for the bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania earlier in the month.

For Obama, it’s the overseas trouble spots in Iraq and Syria and along Ukraine’s eastern border that present the president with his most immediate challenge – pushing U.S. allies beyond their comfort level to confront Russia and the Islamic State militants.

Obama, who has already ordered limited air strikes against Islamic State militants in Iraq, now must decide whether to expand that fight into Syria – a step he has previously been reluctant to take.

The U.S. has been in talks with Britain, France, Australia and Canada on how they can become more involved in confronting Islamic State by sharing intelligence, providing military assistance to Kurdish forces in Iraq and to moderate opposition forces in Syria, and if necessary, participating in military action. But direct use of force could be a tough request to make from countries that were part of NATO forces in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“In a lot of capitals there is retrenchment and they need the United States to lead them and pressure them so they can justify it to their own publics,” said Sam Brannen, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a former Pentagon official in the Obama administration.

One argument for engaging Europe in the fight against Islamic State is the growing number of Europeans among the militants, a point reinforced by the British accent of Foley’s executioner.

William McCants, a former senior adviser at the State Department on countering violent extremism, said that despite European reluctance to engage militarily, Foley’s beheading might make some reconsider.

“The beheading is not just a message to the Obama administration,” McCants, now a fellow at the Brookings Institution, said. “It’s also a message to all the Western governments that `we have some of your own fighting with us and we can unleash them on you back home.'”

Worries about such foreign fighters has grown to the point that Obama next month will chair a United Nations Security Council meeting devoted to the subject.

“We’re concerned about the ability of foreign fighters to come from Western countries and seek to come back,” said Ben Rhodes, Obama’s deputy national security adviser.

In the Ukrainian crisis, the European Union has already imposed tough economic sanctions on Russia, following the U.S. lead in the aftermath of the downing of a Malaysian commercial airliner over eastern Ukraine.

But any further escalations, such as the unauthorized Russian convoy that crossed the border on Friday, could prompt calls from the U.S. to further squeeze the Russian economy, a difficult pitch to make to Europeans whose own economies are more linked to Russia’s.

The convoy returned to Russia on Saturday, easing some of the immediate strain.

But NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen said the convoy crossing was especially troubling because it coincided “with a major escalation in Russian military involvement in Eastern Ukraine since mid-August, including the use of Russian forces.”

A crucial moment could come Tuesday when Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko meets with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Minsk, Belarus.

Reinforcing Europe’s role, German Chancellor Angela Merkel went to Kiev on Saturday and pledged $660 million in loan guarantees to support private investment in infrastructure and schools in war-struck areas. The day before, Obama and Merkel spoke by phone about Ukraine.

The latest worries over Russian intentions in eastern Ukraine come ahead of a NATO summit next week in Wales where the border crisis is one of the dominant themes. Obama will attend the summit, but not before traveling to Estonia where he will reaffirm security commitments to Baltic nations that have been unsettled by Russia’s provocations in Ukraine.

By then, however, it will be September.