LONDON — The World Health Organization says the ongoing Ebola outbreak in Congo still warrants being classified as a global emergency, even though the number of confirmed cases has slowed in recent weeks.

The U.N. health agency first declared the epidemic, the second-deadliest Ebola outbreak in history, to be an international emergency in July. On Friday, it convened its expert committee to reconsider whether the designation is still valid and decide if other measures are necessary.

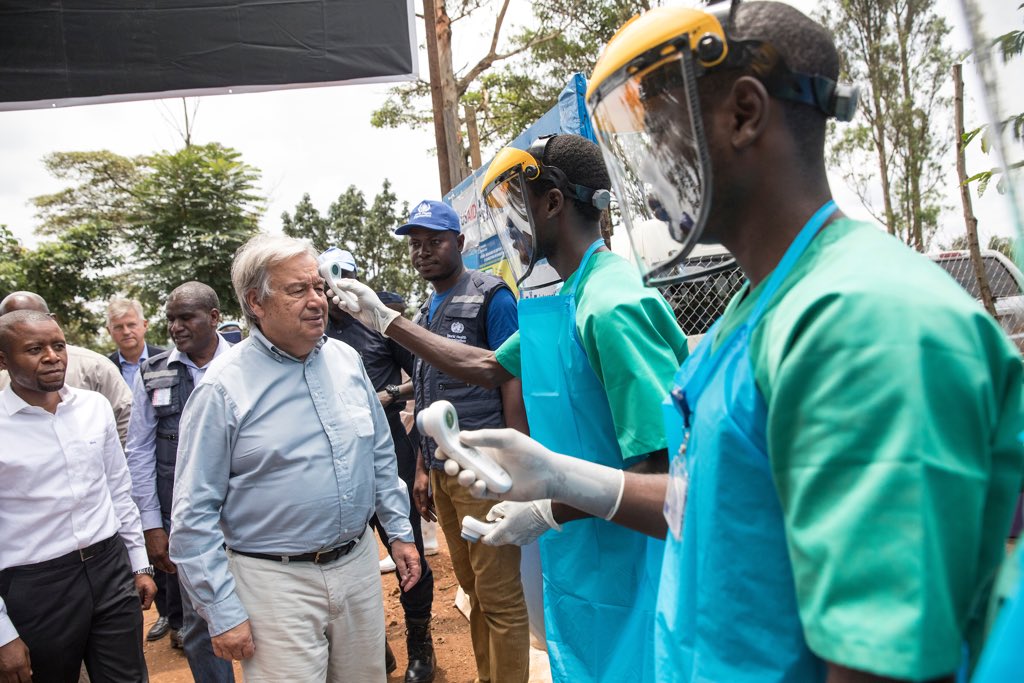

WHO’s director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said the situation remains “complex and dangerous” and that officials must continue to treat every case like it’s the first.

“Every case has the potential to spark a new and bigger outbreak,” he told reporters.

To date, there have been 3,113 confirmed cases and more than 2,150 people have died since the epidemic was first declared last August.

While only 15 new Ebola cases were confirmed last week, WHO noted the vast majority were not in people previously identified as contacts of others infected, suggesting health officials still have difficulty tracking where the virus is spreading.

Dr. Michael Ryan, who heads WHO’s Ebola response, said that some of the most recent cases have been detected in a remote area where there is both legal and illegal mining and is difficult for health officials to reach.

“We still don’t have a full picture of where the virus may be, but we don’t believe we’re dealing with a catastrophic situation,” he said, adding it may be another week or two before officials have a better understanding.

WHO also said nearly a third of people are dying outside of Ebola treatment centres, potentially exposing families and loved ones to the disease.

“When your new cases are not coming off your contact list, that means you don’t have things under control,” said Dr. Armand Sprecher, an Ebola specialist at Medecins Sans Frontieres, or MSF.

Sprecher lamented that attempts to build trust among the wary local population are still failing. “We have not communicated very well over the last year, so can we really do this now? I don’t know.”

Efforts to curb the outbreak have been hampered by violence against health workers — some have been killed — and some local residents suspect international responders of transmitting Ebola rather than stopping it. Misunderstandings have been high in communities that had never experienced the disease before.

In June, the virus spilled into Uganda when a Congolese family, including some already infected, crossed into the country. Two later died of Ebola and the others were sent back to Congo for treatment. The outbreak currently is contained in Congo.

The declaration of this outbreak as an international emergency was expected to bring increased funding and attention to combat the disease. This week, WHO reported that of the $287 million it estimates is needed until December, it has received only about $69 million, although additional funds have been pledged.

This is the first Ebola outbreak to unfold in what has been called a war zone. Eastern Congo is home to numerous armed groups, and their attacks have halted response efforts many times, interrupting efforts to vaccinate people and monitor suspected cases. This outbreak is second only to the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic in West Africa that left more than 11,300 people dead.

Also on Friday, the European Medicines Agency recommended that the Ebola vaccine being used in this outbreak be licensed. More than 270,000 people have received it. The use of experimental Ebola vaccines in the past year has been a welcome development in fighting one of the world’s most notorious diseases.

Last month, MSF called for an independent committee to oversee Ebola vaccination efforts after alleging WHO was unjustifiably restricting use of the Merck-made vaccine. MSF said the fact that so many people have been vaccinated — and yet the outbreak continues to spread — was a damning assessment of response efforts.

Officials are testing a number of Ebola treatments but none is yet licensed.