Music icon, Bob Dylan, once said: “A hero is someone who understands the responsibility that comes with his freedom.” If this definition were to hold true, it is safe to say that we all have the capacity to be “heroes” in our own way – cheesy and lofty-sounding, I know; but true, nonetheless. We can live like a hero; leave a hero’s legacy, when we live our lives with a sense of responsibility for the diverse freedoms we enjoy. Responsible speech, for instance, for the freedom of speech. Mutual respect for the freedom of choice, yet another example. Most of us get the drill – and if you do not, then it’s high time to catch on.

Historically, however, there are those men and women that have taken the concept of heroism to the next level. A level at which they were brave for “five minutes longer” – to reference yet another quote on heroes, this time by author an poet, Ralph Waldo Emerson – than most of us would have been.

These men and women who hold out when freedom is challenged; those who stand for freedom and the ideals that are its very foundations even to the pit of death: these are the ones whom history records in its annals as heroes of nations and peoples the world over.

National hero, defined

Wikipedia – though not always the most accurate of sources – defines a national hero of the Philippines as “a Filipino who has been recognized as a hero for his or her role in the history of the country. Loosely, the term may refer to all Filipino historical figures recognized as heroes, but the term more strictly refers to those officially designated as such.”

Will the officially proclaimed national hero please stand up?

Ironically – and this is a fact that is perhaps, little known – in the Philippines, NO ONE had been officially recognized for the designation of national hero. Do you hear that? It’s the sound of collective gasps of shock and disbelief! It’s true, though – the Philippines has never directly and definitively proclaimed a national hero. Not Rizal (who is largely accepted as the greatest Filipino hero, and as THE national hero), not Bonifacio, not anyone.

The Executive Summary of the Selection And Proclamation Of National Heroes and Laws Honoring Filipino Historical Figure, as published online by the Reference and Research Bureau Legislative Research Service says that :

“No law, executive order or proclamation has been enacted or issued officially proclaiming any Filipino historical figure as a national hero. However, because of their significant roles in the process of nation building and contributions to history, there were laws enacted and proclamations issued honoring these heroes.

Even Jose Rizal, considered as the greatest among the Filipino heroes, was not explicitly proclaimed as a national hero. The position he now holds in Philippine history is a tribute to the continued veneration or acclamation of the people in recognition of his contribution to the significant social transformations that took place in our country.

Aside from Rizal, the only other hero given an implied recognition as a national hero is Andres Bonifacio whose day of birth on November 30 has been made a national holiday.”

Yes, despite the lengthy list of men and women Filipinos generally consider as their national heroes, there has been no official proclamation. A formality, perhaps; but an essential one, nonetheless. We observe holidays in their honour, learn about them at school and such, as we await the day of their official proclamation; when the heroes of the land can stand up and be counted, once and for all.

Unofficially Yours, (signed) Heroes

Among the numerous unofficial heroes of the Philippines, The National Heroes Committee in 1995 recommended nine men and women to be recognized as national heroes. The list included Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo, Apolinario Mabini, Melchora Aquino and Gabriela Silang.

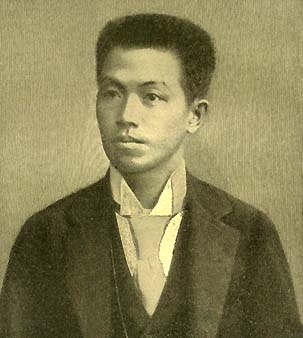

Jose Rizal: Reformist , writer, ladies man

José Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda is perhaps the most “official unofficial” national hero of them all. Born on June 19, 1861, he was a widely acclaimed reformist and key player of the reform movement. A Filipino nationalist, novelist, poet, ophthalmologist, journalist, and revolutionary, Rizal’s mightiest weapon was his quill.

He authored books, poems and essays that stirred the hearts and collective soul of the Filipino people against the ills of their Spanish colonizers. Noli Me Tángere, and El Filibusterismo are two of his greatest works. Rizal was executed by firing squad of the Spanish army on December 30, 1896. His death moved the Filipinos to a bloody revolt against Spain.

Aside from his skill with the quill, Rizal was also quite the ladies’ man. His biographies reveal numerous relations with women; from the purely flirtatious in nature, to those involving deeper affections. Some of the women with whom he was linked are 14-year-old Batangueña Segunda Katigbak; Gertrude Beckett of Chalcot Crescent (London); wealthy and elite Nelly Boustead of the English and Iberian merchant family; last descendant of a noble Japanese family Seiko Usui (affectionately called O-Sei-san); Leonor Valenzuela, and His distant cousin, Leonor Rivera (widely believed to be the inspiration for the character of Maria Clara in Noli Me Tangere), with whom Rizal had an eight-year-long romantic relationship. Rizal eventually settled down with Josephine Bracken, an Irish woman from Hong Kong, who he met when she took her blind father to him for a check-up. They were, however, never able to marry, as Rizal refused to return to the Catholic Church; which he sharply criticized in his writings.

Rizal’s profile is embossed on the one-peso coin. In the Philippines, December 30 is commemorated as Rizal Day.

Andres Bonifacio: Almost president

Given the symbolic nickname “Maypagasa (source of hope),”Bonifacio is known as the father of the Philippine revolutionary movement and the founder of the Katipunan secret revolutionary society.

Born in Tondo, Manila, on November 30, 1863, Andrés Bonifacio y de Castro grew up in the slums and never knew what it was like to live a prosperous life.

He was married twice: first to a certain Monica (of Palomar), who was Bonifacio’s neighbor in Tondo. Monica died of leprosy and they had no recorded children. His second marriage was in 1892, to 18-year-old Gregoria de Jesus.

Numerous Filipino scholars, historians and everyday citizens alike feel that Bonifacio should hold the top “unofficial official” spot of national hero, instead of Rizal. Others believe, as well, that he should have been the Republic’s first president, in lieu of Aguinaldo. Still others claim that trial and subsequent execution of the Bonifacio brothers was unjust. Aguinaldo had the brothers arrested for treason, for their defiance of his authority.

Bonifacio appears on the ten-peso bill, alongside Apolinario Mabini. Aside from Rizal, Bonifacio is the only hero with a public holiday in his honor. Bonifacio Day is celebrated on November 30 of every year.

Emilio Aguinaldo: Polished politician

Emilio Famy Aguinaldo, who went by the moniker of Magdalo (a faction of the Katipunan), is recognized as the first president of the Philippine Republic. Aguinaldo was born on March, 22 1869 in Cavite Viejo (present-day Kawit, Cavite) to well-to do Chinese mestizo parents. He was the seventh of eight siblings. His father, Carlos, was the appointed gobernadorcillo of their area.

Following his father’s footsteps, Emilio became involved in politics, filling the position “Cabeza de Barangay” of Binakayan, a chief barrio of Cavite del Viejo, when he was only 17 years old. He was a central figure in the latter part of the Philippine Revolution, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippine-American War.

Aguinaldo died on February 6, 1964.

He is commemorated on the five-peso bill, on which he displays the Philippine flag from the balcony of his house and proclaims independence from Spain to the Filipino masses below.

Apolinario Mabini: The sublime paralytic

“Dakilang Lumpo” – literally, Heroic Paralytic – was the nickname that Apolinario Mabini y Maranan went by. He was born on was born on July 22 or 23, 1864 (the registration of his birth is uncertain) in Barangay Talaga in Tanauan, Batangas. Philippine history texts refer to him as “the Sublime Paralytic”, and as “the Brains of the Revolution;” while his enemies and detractors called him the “Dark Chamber of the President.”

Apolinario Mabini was appointed prime minister and was also foreign minister of the newly independent dictatorial government of Aguinaldo on January 2, 1899.

There was much controversy surrounding the cause of his paralysis, with strong rumours flying about that it was the result of a venereal disease; syphilis, to be precise. However, his bones were exhumed after his death and autopsy results conclusively proved that poliomyelitis had caused the condition.

Mabini died of cholera on May 13, 1903.

He is depicted on the ten-peso bill, with Andres Bonifacio and other symbols of the Katipunan.

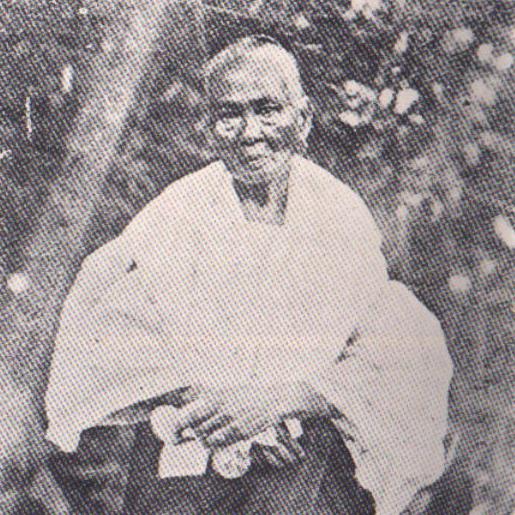

Melchora Aquino: Mother of all

Born to a peasant couple in Banlat, Kalookan City, on January 6, 1812, Melchora Aquino de Ramos or Tandang Sora (Elder Sora), as she was known, helped the Katipuneros under the leadership of Andres Bonifacio. Brave and compassionate Melchora provided the revolutionary soldiers with food, shelter, medicine, and other material needs. She owned and operated a small home-based store, which served as a front for her heroic activities with the revolutionaries.

Recognized as the “Grand Woman of the Revolution,” “Mother of the Philippine Revolution,” and the “Mother of Balintawak,” Melchora never attended school, but was literate at a young age. She was also a talented singer, performing at church and local events.

Melchora had six children of her own whom she reared predominantly by herself, as her husband passed away at an early age.

She was exiled to Guam for her involvement with the revolutionary troops, and was allowed to return home when the Americans took control of the Philippines in 1898.

She died at the age of 107, on March 2, 1919.

Melchora is also the first Filipina who appears on a Philippine peso banknote; specifically, the 100-peso bill from the English Series (1951–1966). Her image was later stamped on the 5-centavo coin, which was issued from 1967 to 1992. A district in Quezon City and a road were likewise named after Grand Mother Tandang Sora.

Likewise, Tandang Sora Street in the city of San Francisco, California is named in her honor.

Gabriela Silang: “la Generala” continues the fight

María Josefa Gabriela Cariño Silang was the wife of the Ilocano insurgent leader, Diego Silang. When her husband was killed in 1763 by Miguel Vicos, a Spanish mestizo who bore grievances against the rebel leader, Gabriela decided to continue her slain husband’s fight for freedom.

Feisty and fierce Gabriela was born on March 19, 1731 in the town of what is now known as Caniogan, Santa, Ilocos Sur. However, the local folk of neighbouring Abra claim she was born in what is now the town of Pidigan. She is reportedly the child of a certain Anselmo Cariño, and a servant in the Cariño household.

Gabriela was later on adopted by rich businessman Tomás Millan, whom she later married at the age of 20. She was widowed three years later, and subsequently re-married in 1757 to 27-year-old Diego Silang.

She became one of Diego’s closest advisers in the armed struggle for freedom, and figured heavily in her husband’s collaboration with Great Britain.

Upon her husband’s death, the widowed Gabriela took on the role as commander of rebel troops, and her popular image as the bolo knife-wielding “la Generala” on horseback is derived from this period.

She is remembered through many monuments, such as the one commissioned and installed at the corner of Ayala and Makati avenues in Makati City’s Central Business District, by the Zobel de Ayala family . The metal statue was cast by José M. Mendoza in 1971, and was inaugurated by Silang’s descendants Gloria Cariño and Mario Cariño Merritt.

Gabriela is also commemorated by the Order of Gabriela Silang, the only third class national decoration awarded by the Philippines, and whose membership is restricted to women. Likewise, the The organisation and party list GABRIELA (“General Assembly Binding Women for Reforms, Integrity, Equality, Leadership, and Action”), staunch advocate of women’s rights and issues, was established in her honour in April 1984.

Other figures on the list recommended by the National Heroes Committee are Marcelo H. del Pilar, Sultan Dipatuan Kudarat,and Juan Luna.