WASHINGTON — Elizabeth Warren ended her once-promising presidential campaign on Thursday after failing to finish higher than third place in any of the 18 states that have voted so far. While the Massachusetts senator said she was proud of her bid, she was also candid in expressing disappointment that a formerly diverse field is essentially now down to two men.

“All those little girls who are going to have to wait four more years,” Warren told reporters outside her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as her voice cracked. “That’s going to be hard.”

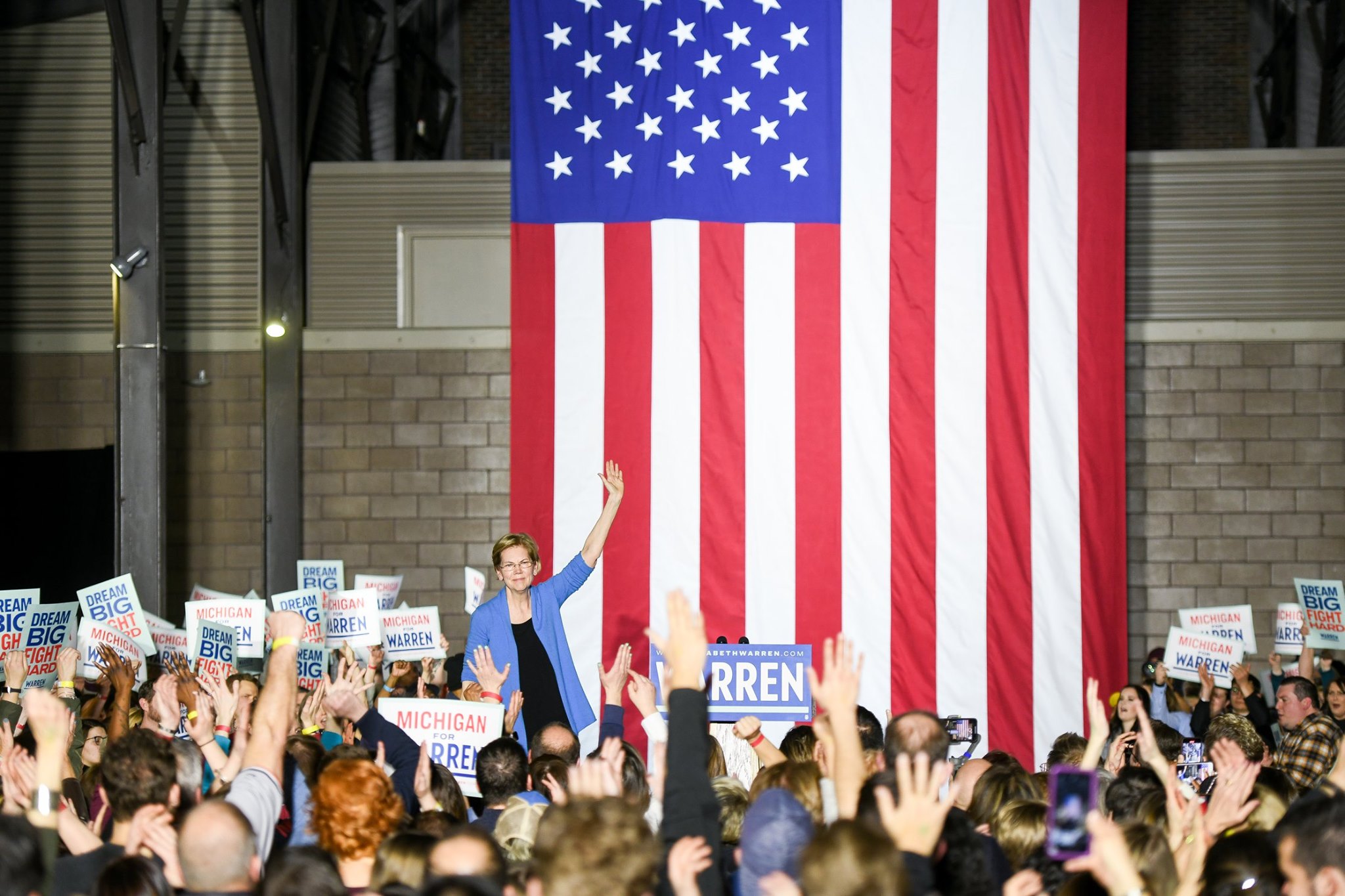

Known for having “a plan for that,” Warren electrified progressives for much of the past year by releasing reams of policy proposals that addressed such issues as maternal health care, college debt, criminal justice reform and the new coronavirus. She planned to pay for many of her ambitious proposals with a 2 cent tax on fortunes worth more than $50 million, an idea that prompted chants of “Two cents! Two cents!” at her rallies.

But that energy — and an impressive organization — didn’t translate into support once voters started making their decisions last month. She failed to capture any of the 14 states that voted on Super Tuesday and finished an embarrassing third in Massachusetts.

The Democratic contest now centres on Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who is trying to rally progressives, and former Vice-President Joe Biden, who is appealing to moderates. They are both white men in their late 70s, a fact that is prompting soul-searching for some Democrats who heralded the historic diversity that characterized the early days of the primary.

“I think we all have to really interrogate why being for someone other than someone who looks like almost every other president we’ve had, in terms of age and gender, why everything else is seen as risky,” said Cecile Richards, the former president of Planned Parenthood.

While she said she will rally behind whoever emerges as the Democratic nominee, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi also lamented the challenges facing women in politics.

“Every time I get introduced as the most powerful woman, I almost cry because I wish that were not true,” she said Thursday. “I so wish that we had a woman president of the United States.”

Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard is still in the race but faces steep odds and has won just two delegates in her quest for the nomination.

Although she’s no longer a presidential contender, Warren will likely remain a force in Democratic politics and could play a prominent role in a future administration if the party wins the White House. Clearly aware of her power, Warren didn’t rush to endorse either Sanders or Biden.

Warren suggested Thursday that she would take her time before deciding whom to back. She didn’t endorse Sanders in 2016 — something that infuriated some of his supporters — and only backed Hillary Clinton after she effectively won the nomination.

Top advisers who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private conversations indicated Warren wouldn’t wait that long in 2020.

Sanders wasted little time making an appeal to Warren backers, saying in Vermont on Thursday, “I would simply say to her supporters out there, of which there are millions: We are opening the door to you. We’d love you to come on board.”

But the divisions among Democrats run deep. Toni Van Pelt, the president of the National Organization for Women, urged Warren against siding with Sanders and noted Biden’s involvement in the passage of the Violence Against Women Act.

“She has a lot of leverage right now. We do trust her to make the right decisions on how to proceed. But we’d like her not to rush into this,” Van Pelt said. “Sanders doesn’t have a record. He’s really, as far as we know, done next to nothing for women and for our issues and for the things that are our priorities.”

After a strong summer, Warren’s poll numbers began to slip after a series of debates in which she repeatedly refused to answer direct questions about if she’d have to raise taxes on the middle class to pay for universal, government-funded health care under a “Medicare for All” program. Warren’s top advisers were slow to catch on that not providing more details looked to voters like a major oversight for a candidate who proudly had so many other policy plans.

When Warren finally moved to correct the problem, her support eroded further. She moved away from a full endorsement of Medicare for All, announcing that she’d work with Congress to transition the country to the program over three years. Biden and other rivals pounced, calling Warren a flip-flopper, and her standing with progressives sagged as Sanders stood by his unwavering support for government-run health care immediately.

After long avoiding direct conflict, Warren and Sanders clashed in January after she said Sanders had suggested during a private meeting in 2018 that a woman couldn’t win the White House. Sanders denied that, but Warren refused to shake his outstretched hand after a debate in Iowa — which only further hurt her polling numbers.

By the time the campaign turned to the South Carolina primary late last month, an outside political group began pouring millions of dollars into television advertising on her behalf. That forced Warren to say that, although she rejected super PACs, she’d accept their help as long as other candidates did. Her campaign, meanwhile, shifted strategy again, saying it was betting on a contested convention.

Warren said outside her house on Thursday that “gender in this race, that is a trick question,” since any woman running for office who acknowledges sexism is derided as a “whiner” and those who don’t aren’t accepting reality. But she nonetheless suggested her road might have been harder than that of the male candidates.

“I was told at the beginning of this whole undertaking that there are two lanes, a progressive lane that Bernie Sanders is the incumbent for and a moderate lane that Joe Biden is the incumbent for,” she said. “And there’s no room for anyone else in this. I thought that wasn’t right, but, evidently, I was wrong.”

———

Associated Press writers Steve Peoples in New York and Laurie Kellman in Washington contributed to this report.