LETICIA, Colombia — Leaders of several South American nations that share the Amazon met Friday to discuss ways to increase protection of the world’s largest rainforest.

But the one-day conference in Leticia, a town on the Amazon River where the borders of Colombia, Peru and Brazil meet, ended with little concrete action and exposed deep ideological and political rifts over sustainable development of the Amazon.

While Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno, who was born in the Amazon, offered an emotional, song-filled homage to the diverse plant and animal life with which he was raised, his Brazilian counterpart, Jair Bolsonaro, attacked leaders of wealthy countries, accusing them of conspiring against the Amazon nations’ sovereignty.

“We are killing the earth, and all of us are responsible,” said Moreno, who was on the edge of tears as he recounted flying over the Amazon River, which he compared to a giant, dead Anaconda snake.

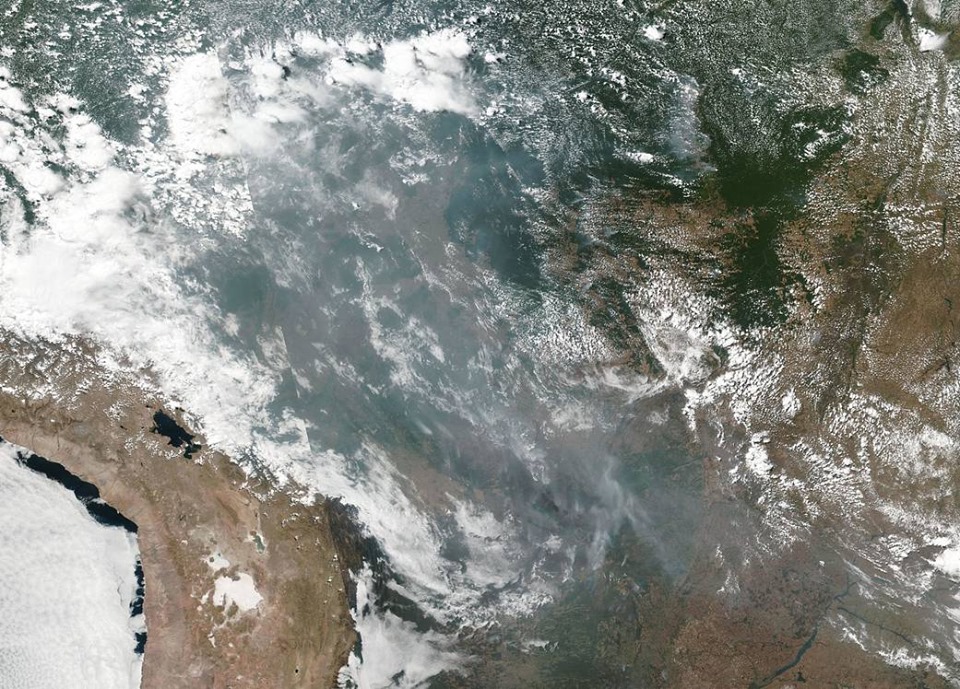

The host, Colombian President Ivan Duque, and his Peruvian counterpart, Martin Vizcarra, called for the meeting following global outrage over a surge in the number of fires in Brazil’s Amazon region this year, which triggered a wave of protests at Brazilian diplomatic missions worldwide this week over Bolsonaro’s alleged indifference to environmental concerns. Since the start of the year, there have been more than 95,500 fires in Brazil, up 59% from the same period in 2018, according to Brazilian government data. Neighboring Bolivia has also been ravaged by wildfires.

Efforts to jointly protect the Amazon began with the 1978 signing of a treaty by eight Amazon nations. All of them were represented at the summit with the exception of socialist-run Venezuela, whose exclusion was criticized by Bolivian President Evo Morales, a close ally of embattled Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro.

But co-operation among the countries has stalled even as threats from climate change, unchecked development as well as illegal mining and drug trafficking have increased in the region. A 16-point action plan signed Friday as part of the “Leticia Pact for the Amazon” only commits each country to sharing weather data and taking other steps to make it harder for miners, loggers and ranchers to illegally slash and burn forest.

“We have to take concrete action because good will alone is not sufficient,” Vizcarra said.

Analysts were skeptical that multilateral co-operation could reverse deforestation.

“Most of these countries don’t even have enough capacity to combat illegal activities within their borders,” said Adriana Ramos, a researcher at Instituto Socioambiental, a Brazil-based group.

Instead of focusing on those common challenges, the far-right Bolsonaro lashed out at an array of critics — socialists, indigenous groups and French President Emmanuel Macron. He said such forces alternately want to appropriate for themselves the Amazon’s riches or shut off from the modern world a region that is home to more than 34 million people.

“This international outrage has the only goal of attacking Brazil’s sovereignty,” said Bolsonaro, who participated via videoconference due to medical restrictions preventing him from flying. “I regret that Brazil has been asleep for decades and is only now waking up to this threat.”

On the other side of the political spectrum, Morales blamed the spread of capitalism for the Amazon’s destruction.

“The profits, the luxuries and the consumption patterns enjoyed by a few are causing great damage to those who inhabit the earth,” he said. “Our planet can exist without human beings, but mankind can’t exist without Mother Earth.”

The meeting, held in a thatch-roofed traditional building, began with the leaders being welcomed by a delegation of indigenous dancers with ornamental headdresses. Honoring the region’s vibrant ancestral culture, several leaders wore necklaces made of beads gathered from the Amazon.