Travelling along the uncharted coasts of Newfoundland, a clergyman came across an orphaned brother and sister living alone in an isolated cove, with a baby on the way.

He determined there could only be one explanation for the pregnancy. After he confronted them about the child’s paternity, the brother chased the outsider away with a rifle, leaving the family to mind their craggy corner of the Earth.

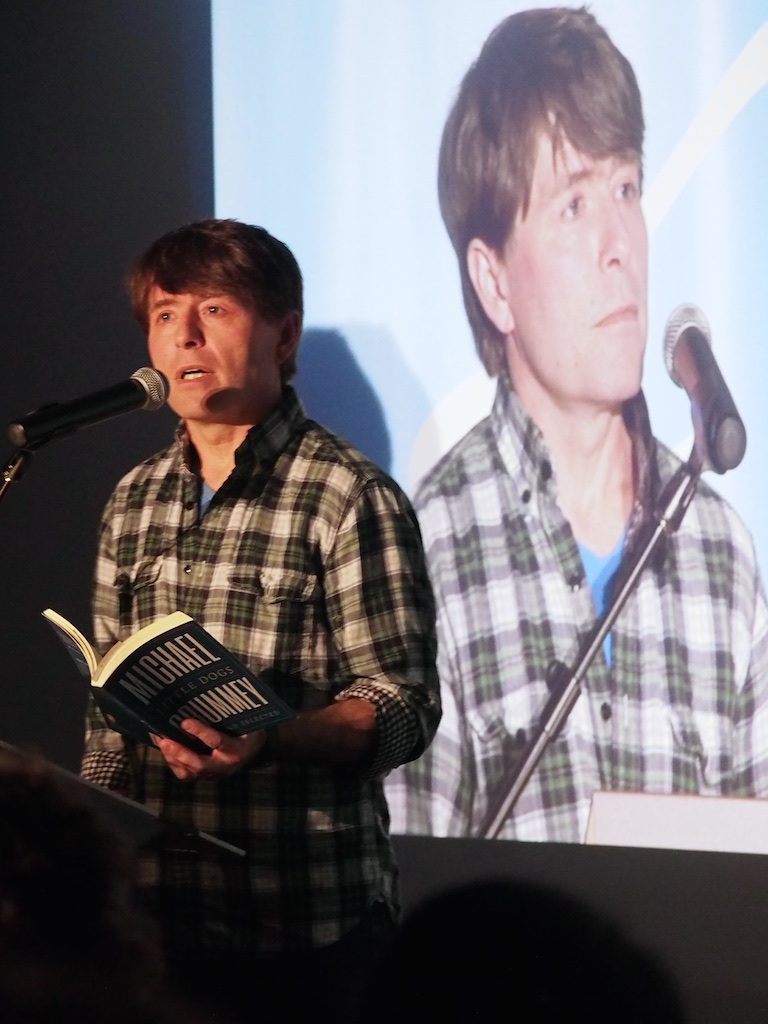

When Newfoundland writer Michael Crummey dug up the clergyman’s one-paragraph account of this encounter in the provincial archives, he knew there was a story to be told, but wasn’t sure if he was up to the task of telling it.

He worried a tale inspired by the account would seem contrived, oversentimental or even exploitative.

It would take Crummey years and several abandoned attempts to find a way into his latest work of historical fiction “The Innocents,” published by Doubleday Canada, which hits shelves Tuesday.

Despite the book’s incestuous undertones, Crummey hopes readers will be able to relate to the coming-of-age narrative at its centre: the jarring realization that there are limits to one’s understanding, even about oneself.

“I think that all children, in a way, live in a world that is only partially revealed to them. That ignorance is, in a sense, a congenital part of childhood,” Crummey said by phone from St. John’s.

“Eventually, it becomes clear that there are other things going on that no one has explained, and there’s a real shame involved in that.”

Crummey said, in some ways, his home province of Newfoundland and Labrador has been the “main character” of his previous four novels, which have earned nominations for the Giller Prize, Governor General’s Literary Award and Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize among other accolades.

But in “The Innocents,” Crummey said the book’s 18th-century setting on a rocky shore in northern Newfoundland felt so removed, this sense of place became secondary.

Instead, the story focuses on the bond between Ada and Evered Best, who after losing their parents and infant sister to illness, are left to fend for themselves in the desolate harbour they call home.

The children live at the mercy of the ocean, which by turns sustains them and drives them to the brink of survival, its whims as mysterious as the world that lies beyond the horizon.

And as they grow older, the siblings seem to become strangers to themselves, their bodies seized by impulses that arouse both pleasure and shame.

In this innocence and ignorance, Crummey said he sees Ada and Evered’s story as so universal, it can be traced back to the first man and woman.

He drew parallels to the biblical story of Adam and Eve, who after eating from the tree of knowledge, recognize their own nakedness and for the first time feel compelled to cover themselves.

Every child experiences this exile from Eden, said Crummey. But Ada and Evered remain sequestered in their unsparing paradise — fallen and forsaken.

“There’s a kind of blindness to childhood, and to these two children in particular, because of what they don’t know,” Crummey said. “As they become aware of how blind they are, out in the world, that feels like a personal failing.”

Of the two siblings, Ada is more drawn to the forbidden fruits of beauty, collecting curios such as shells, a silver button and a bone pendant stolen from a Beothuk burial site.

It’s an artistic appetite, or perhaps greed, that Crummey recognizes in himself.

As a historical fiction writer, Crummey said he too has pillaged the annals of the past for his own esthetic ends. In recent years, he’s come to see storytelling as a force as creative as it can be destructive, and wrestled with where his work falls on that spectrum.

“This brother and sister who I found in the archives were real people, and I have no idea what their story was. And for me to pretend I know is an act of appropriation,” said Crummey.

“I think that’s something that I increasingly feel like I have to acknowledge to write at all.”