OTTAWA — Those who sit on the bench can soon expect extra guidance on what they should — and should not — be doing after retirement, according to organizations that oversee lawyers and judges.

The post-retirement contributions of Supreme Court judges is under scrutiny after the federal ethics watchdog’s report on the SNC-Lavalin scandal revealed how their opinions were sought after by players on all sides of a dispute at the heart of the Liberal government.

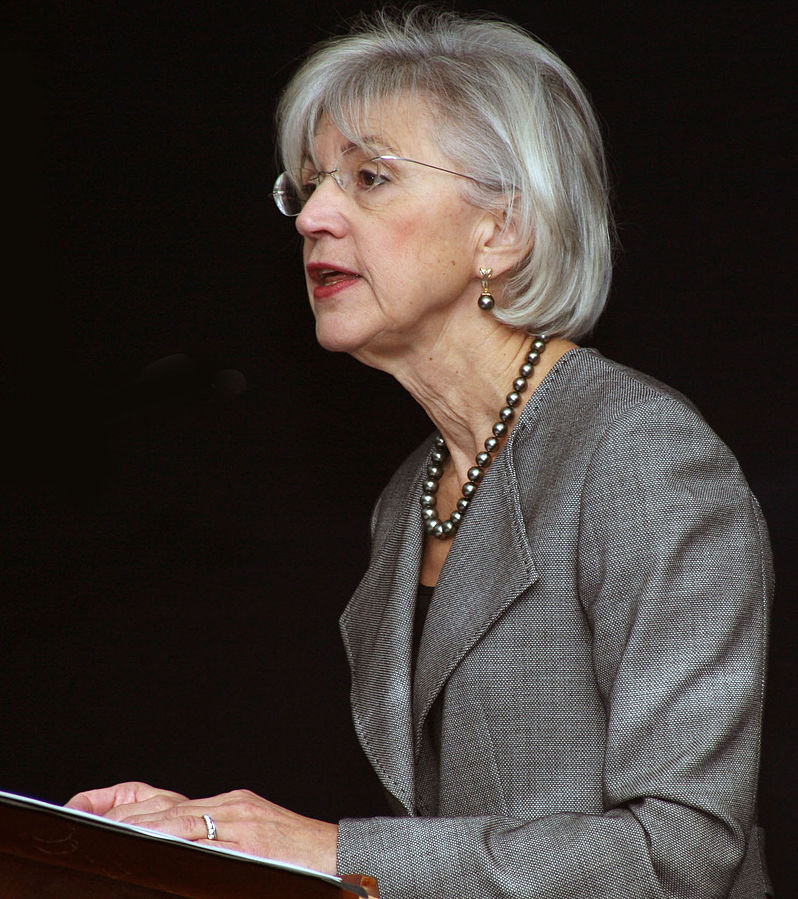

That included retired chief justice Beverley McLachlin. Senior aides in the Prime Minister’s Office urged Jody Wilson-Raybould, who was attorney general at the time, to ask McLachlin for advice on the legality of intervening in the case against the Montreal engineering giant.

They did not tell her that both SNC and a senior PMO adviser had already had preliminary talks with McLachlin about providing her opinion, or acting as a mediator between SNC and the public prosecutor over entering into a remediation agreement. The report said McLachlin, who did not respond to a request for comment Thursday, had expressed her willingness to meet with Wilson-Raybould, but had reservations about it.

The report also noted that former Supreme Court justice Frank Iacobucci, who was legal council for SNC-Lavalin, wrote and circulated to government an analysis on the legality of overturning the public prosecutor’s refusal to negotiate a remediation agreement with the company. And he solicited a second legal opinion on the matter from yet another former Supreme Court justice, John Major.

The Canadian Judicial Council and the Federation of Law Societies have been working together on updating the ethical principles for judges, including a look at their careers after retirement.

“Judges, like all of us, are experiencing a greater life expectancy and quality of life,” Johanna Laporte, spokeswoman for the Canadian Judicial Council, wrote in a statement.

“Some are retiring early,” she said. “This means that many former judges want to continue to contribute to society in a meaningful way.”

Individual courts and provincial law societies already have rules for former judges who return to legal careers, such as a cooling-off period before they can appear in court.

The new guidelines could go further.

Laporte said a majority of those who participated in public consultations on the issue agreed judges should not argue a case or appear in court, with even more saying retired judges should not be able to leverage their former position to gain a business advantage.

“(We) have been discussing how ethical principles can best complement the rules,” wrote Laporte, who expects the revised guidelines to be published next year.

The Federation of Law Societies issued a statement saying it has also consulted on possible amendments that “would impose additional restrictions and obligations on retired judges who return to the practice of law.”

Michael Spratt, an Ottawa-based criminal defence lawyer, said it could be tricky to come up with rules that still allow retired judges some leeway in sharing their expertise.

“I think that there is a risk in being overly restrictive in rules about what judicial actors can do,” he said. “We might be losing good applicants to the bench and we might also be depriving ourselves of some very, very good expertise that can provide a real benefit.”

Still, Spratt said he was concerned by the extent to which the report revealed the PMO was trying to involve retired Supreme Court judges to help them persuade Wilson-Raybould.

“I think that the easiest solution is for governments to constrain themselves and to stop using judges, or former judges, as political pawns,” he said.

“Using judges in this way, especially when there are partisan political interests at stake, risks eroding public trust in a very important pillar of our democracy, and that is the judiciary,” said Spratt, whose mother-in-law, Louise Arbour, is also a retired Supreme Court justice.

“If the public thinks that judges can be bought or swayed, even if they’re retired, that might erode important aspects of our democracy and reduce confidence in those institutions,” he said.

Wilson-Raybould, who had hired former Supreme Court justice Thomas Cromwell to advise her on what she could say publicly about the SNC-Lavalin controversy, said her biggest issue with the PMO involving other retired judges is that she was kept in the dark.

“Governments, public officials are at liberty to seek advice from people, retired justices included. I am not going to pass judgment on whether it was proper. It happens,” she said in an interview with The Canadian Press.

“What I feel is difficult to understand or potentially, I don’t want to use the word strange but I will, is that this happened unbeknownst to the attorney general of Canada,” she said.

— With files from Kristy Kirkup