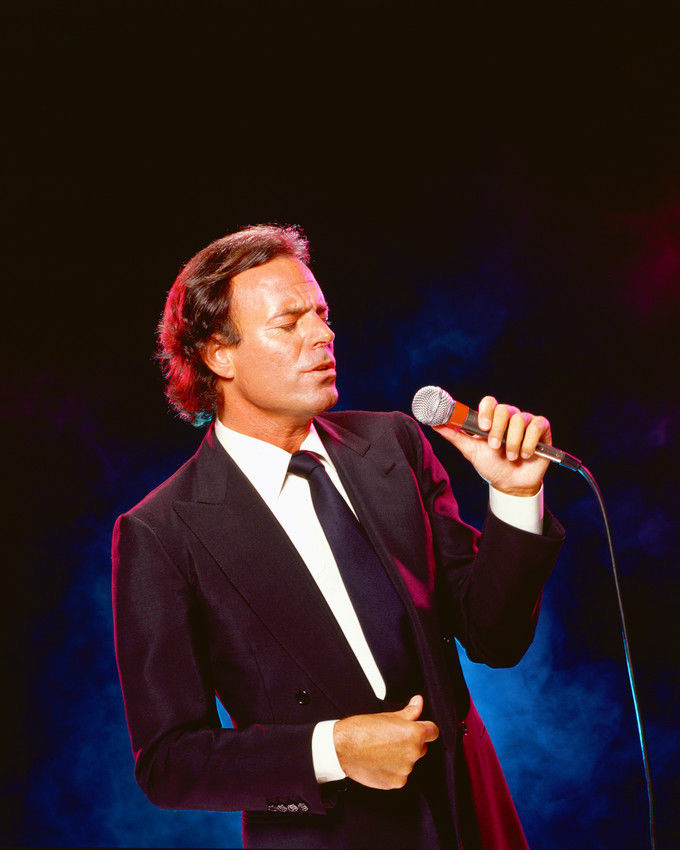

NEW YORK — At 75 and after a five-decade-long career, Julio Iglesias keeps performing internationally, driven by his passion and, above all, a relentless discipline.

It’s something the Spanish crooner says he had to learn early on, after a nearly fatal car accident frustrated his plans to play professional soccer.

“In fact, my life has been a miracle,” says Iglesias, recalling how he spent “months and months” in bed unable to move, and then needed canes to walk for more than two years.

The “magical” accident — as he calls it today — stripped him of his physical strength and his life as he knew it, but it also gave him a greater awareness of other people’s struggles and helped him learn to fight, to listen, to look people in the eye. “You see life differently, you learn to live again,” Iglesias says.

It also set him on the path of music. While Iglesias was struggling to move his arms and fingers, his physician-father’s assistant gave him an old guitar as a gift.

“I learned five or six harmonies from a music book that I had, don’t think I learned much more than that because I couldn’t move my fingers that fast. That is why my first songs have two or three harmonies,” the singer recalls with a laugh.

But those few chords were more than enough to launch an impressive career. Iglesias, who also studied law, debuted in 1969 with the album “Yo canto” and went on to become one of the most successful singers in the world, with more than 250 million records sold around the globe.

He has received awards and accolades that include the Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts from Spain, was named a knight of France’s Legion of Honor and, early this year, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys. He is currently touring in Europe ahead of a series of shows in the U.S. that begin Sept. 14 in Boston.

How does he do it?

“Everything was a bigger struggle for me, everything required a bigger effort, so I understood that the sole basis for my future was discipline, and I maintain that discipline today, at 75,” Iglesias assures. “I mean, going out onstage to sing is an act of discipline and of absolute passion. Passion is natural, but discipline is willpower.”

In a recent interview with The Associated Press from the Dominican Republic, where he lives, Iglesias spoke about his life, his career, his family and his regrets. Remarks have been edited for clarity and brevity.

AP: It’s been 50 years since the release of “Yo canto” and here you are, still singing strong. Besides discipline, what else has worked for you? Any advice for the younger generations?

Iglesias: Giving advice is very easy … but giving advice to younger people is hard. I have two older sons that sing, Julio and Enrique, and they don’t allow me to give them advice. They don’t, neither of them. And when we start talking about music, the conversation takes a different turn and goes to other places because they need their own free will, the absolute freedom to choose what they like. That is important.

AP: How did you develop that unique singing style?

Julio Iglesias: In life, it is very important to be natural, because that’s what creates your style. Good or bad, liked or disliked, but your style has to be unmistakable. When we speak of Pavarotti, Placido, Carreras or Bocelli, we are fundamentally speaking about great styles. I think the style is more important than the voice.

AP: In retrospective, anything you regret about your life or your career?

Iglesias: I regret not having taken more advantage of time — of the solidity of time, the intention of time. That’s why I don’t like to sleep much anymore. Had I known when I was 20 that I was going to be a musician, I would have taken to the piano, I would have taken the guitar more seriously, I would have perfected my knowledge of music.

AP: But here you are, one of the biggest artists in the world half a century later. You didn’t do so badly…

Iglesias: No, but I think you must learn as much as you can, and also know how to learn. A few days ago, I recalled when I had a huge American success with the album “1100 Bel Air Place” and I gave 12 or 14 concerts at the Universal Amphitheater. Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Bob Hope, legendary artists that have since passed away, came to see me, and I didn’t make the time. It didn’t occur to me to approach them, to have dinner with them and ask them about their lives to learn from them.

AP: You career demanded constant travelling. Would you have liked to spend more time with your family?

Iglesias: I don’t think — and I always say this clearly — that it affected my relationship with my children. Quite the opposite. Enrique is a singer, Julio is a singer, Chabeli did television for many years. Then there is Miguel, the only one who doesn’t like to sing. Rodrigo, who loves music. And the younger girls, who now want to be models or something. And my little Guillermo plays the piano, the drums, he is a natural musician. I think all those things happened because I opened a highway for them. Of course, they need to follow it, amplify it and seek other roads, separate from that road. But that opened a door that is the door of light, and the door of light is magical. That makes me not regret it. If I had taken much more care of my children, they wouldn’t have lights. And I would have wasted my time.

AP: At 75, anything you would still like to achieve?

Iglesias: Many things. I like a lot to read; I don’t read that much anymore. I loved to travel; I travel less. In reality, time puts many things in its place. Stairs seem much longer and steeper. Everything after 65 starts to be a part of your life that you have to legitimize based on discipline. And give thanks continuously. In fact, my life has been a miracle. Almost like a novel: a person that plays soccer, that has an accident and almost dies, that studies law and starts to sing, that doesn’t know how to sing and sings, that doesn’t know how to walk and runs, that was a skinny boy and becomes stronger. I was nobody. And I’m still nobody because deep down we are all nobodies. Deep down it’s the people that make us somebody.