OTTAWA — External Affairs Minister Joe Clark didn’t try to sugarcoat it for Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and their cabinet colleagues.

Over the previous 48 hours, stunned disbelief had sunk in across the globe after the Chinese army used tanks and guns to kill hundreds, if not thousands, of pro-democracy student protesters in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The big question for the Canadian Progressive Conservative government of the day was: what do we do about China now?

Clark “expected the situation to worsen, and could not rule out the possibility of civil war,” say the declassified minutes of the June 6, 1989 meeting of the cabinet committee on priorities obtained by The Canadian Press.

The Mulroney government grappled with what to do in a series of cabinet meetings 30 years ago this month, the details of which are now revealed in meeting minutes that have been released under access-to-information legislation. The documents provide a window into how the government dealt with what the worst period of Sino-Canadian relations — until the one now facing Justin Trudeau and the Liberals.

Canada is caught in the crossfire of a United States-China trade war. Two Canadian men, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, are under arrest in China facing allegations of espionage and endangering national security — detentions Canada and the U.S. view as arbitrary. Many see that their detentions as retribution for Canada’s decision to arrest Chinese high-tech scion Meng Wangzhou on an extradition request from the U.S. China has also banned some Canadian canola shipments and is cracking down on other agricultural exports.

As was the case in the late 1980s, today’s Canada-China crisis was preceded by a period of hope for greater economic and social integration between the two countries. The Mulroney government hoped Canadian engagement would lead to greater freedoms in the China, as did the current government under Trudeau.

Tiananmen Square changed that for Mulroney. For Trudeau, it was the fateful intervention at Vancouver’s international airport six months ago, when the RCMP arrested Meng, the chief financial officer of Huawei, so she can face extradition on fraud charges related to violating Iran sanctions in the United States. Beijing has accused Canada of doing the political bidding of the U.S. as the Trump administration blasts it with tariffs and threats of more.

Different circumstances, Mulroney says today, but with an underlying repetition of history.

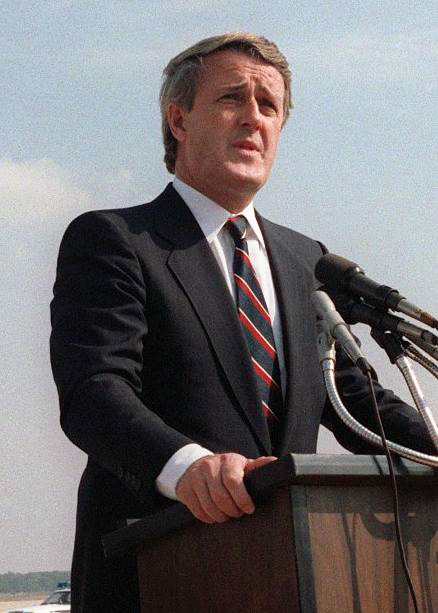

“In those days the bipolar world, with the United States and the Soviet Union, had just ended. Then we’ve gone 30 years without one, in a unipolar world led by the United States,” Mulroney said in an interview.

“Now, we’re in bipolarity again with China not only emerging as a rival world power to the United States but flexing its muscles in the South China Sea and elsewhere, and on trade issues, making it much more difficult for countries like Canada to articulate a view in the national interest.”

Mulroney said the events of 30 years ago were “cataclysmic in foreign affairs.”

“It was very unsettling for us all because we all had hoped that the Chinese sweep towards prosperity would be accompanied by an appreciation of democracy and respect for human rights,” he said.

Clark, he said, “did a superb job” of leading the Canadian response when that hope suddenly disappeared on June 4, 1989.

That job started at 10 a.m. on June 6, 1989, when Clark addressed Mulroney and the 12 men and one woman — employment and immigration minister Barbara McDougall — seated in a cabinet committee room. It was the day after his 50th birthday.

Clark said there were reports of violence and fighting spreading outside Beijing, which led to his remark about civil war still being a possibility. He described the evacuation arrangements for 300 Canadians in Beijing and another 300 outside the capital.

“He explained that his officials were looking at ways of referring the situation to the UN Security Council, in spite of the rule that matters internal —” the word is underlined in the document “— to a country normally cannot be referred to the council,” say the meeting notes. Canada had just begun a two-year temporary term on the council.

A decade later, Canada would help create the UN’s “responsibility to protect” doctrine, or R2P. It allows for the lawful intervention in the internal affairs of a country if its government is threatening its citizens — subjecting them to genocide or other crimes against humanity.

In 1989, Mulroney ended that initial cabinet meeting with three orders. One of them was to tell Canadian diplomats at the UN to “refer the situation in China to the UN Security Council.”

When the full cabinet convened nine days later, the government’s plan was taking shape. There was to be no Canadian-led opprobrium at the Security Council, but Clark offered some other updates at the June 15 meeting.

Among them: Radio Canada International was to start broadcasting into China in Mandarin on June 20, 10 months ahead of a previous plan to do that. “Their emissions would likely be blocked, but it would be a worthy attempt to transmit factual reports into the country,” the minutes state.

At a June 19 ministers’ meeting, more details: “We will be joining Radio Australia, Voice of America and the BBC in our collective effort to keep the truth alive,” say notes for a presentation to the cabinet committee on foreign and defence policy.

At the June 15 cabinet meeting, Mulroney announced another major decision: relations with China would not be severed. He wanted to “maintain a ‘people to people’ link,” the minutes say.

Mulroney noted “the shock” of most Canadians towards China. “Canadians had welcomed the apparent trend towards openness in China. Canadians were abhorred by the true brutality of the regime which resided under the patina of growing openness.”

Clark elaborated on the need to continue engaging with China, which was discussed further by the cabinet committee on foreign and defence policy on June 19.

Clark’s speaking notes for the meeting raise the question of “what sort of relationship does Canada want with China” after the massacre. “The answer of course hinges on a whole series of issues, some not all that clear at the moment. For example, how permanent is this reversal in the democratization process? Will another shoe drop?”

While Canada wasn’t accepting China’s international call for “business as usual,” it still had to recognize the “importance of preventing China from sliding back into international isolationism.”

Another briefing document for the meeting stated: “It is better to keep China within the community of nations, better to readjust our relations to downgrade government-to-government ties and to emphasize people-to-people ties.”

Today, Mulroney said there is no choice for the Trudeau government but to continue engaging with China as it tries to free Kovrig and Spavor.

Mulroney has advocated dispatching a higher-powered delegation to appeal directly to Chinese leaders. He said it should be led by former Liberal prime minister Jean Chretien and his son-in-law Andre Desmarais, the Power Corp. executive, both of whom are well-connected in the People’s Republic.

The government recently secured another high-profile commitment for help: U.S. Vice-President Mike Pence said President Donald Trump planned to raise Kovrig and Spavor with Chinese Premier Xi Jinping at the G20 leaders’ summit in Japan at the end of June. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Thursday he’s considering his own meeting with Xi at the G20 (though Xi would have to agree).

Given the degeneration of relations between Trump and Trudeau over the last year, something Pence’s recent visit appeared largely aimed at repairing, Mulroney suggested the American help with China is long overdue.

“That’s the way the Americans used to treat Canada all the time,” he said. “And I’m glad to see they’re back on the same wavelength.”