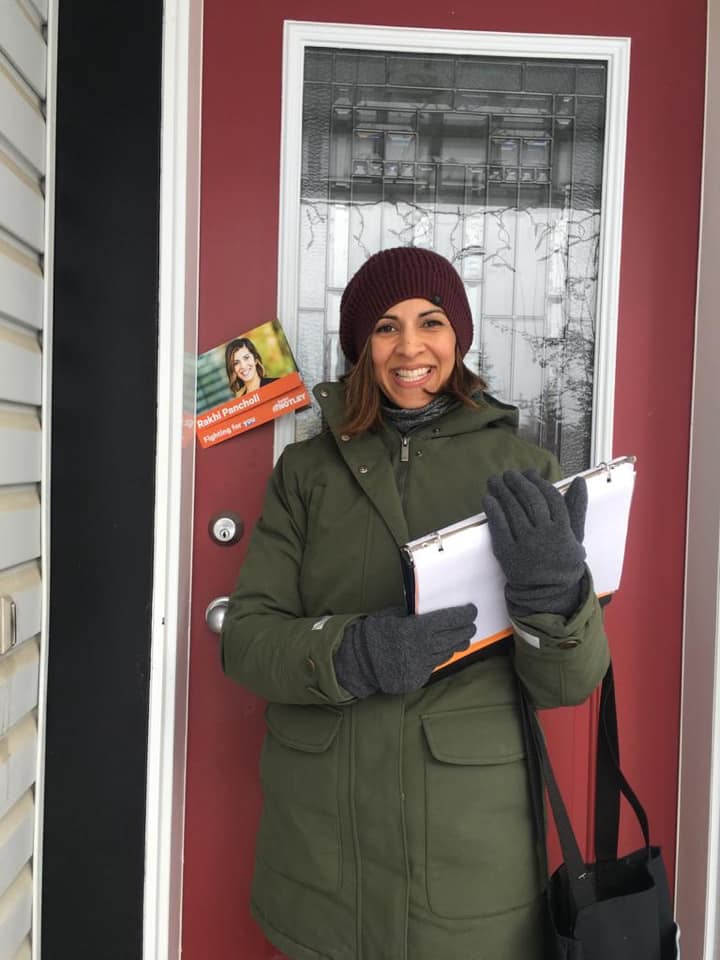

When Rakhi Pancholi was asked to run in the Alberta election, she was well versed in the reasons women give for avoiding politics.

Through her work with ParityYEG, an Edmonton group aimed at getting more women to run for office, Pancholi has heard concerns over career setbacks, financial strain, sexist vitriol and balancing the political grind with domestic tasks mostly shouldered by women.

“It’s time for me to walk the walk,” the 41-year-old mother recalled thinking during a coffee with Health Minister Sarah Hoffman, a friend of a friend who made the overture.

“If I can’t do it myself, I can’t ask other women to do this.”

Pancholi, the NDP candidate in Edmonton-Whitemud, said it usually takes at least three asks before a woman decides to run. For her, it only took one.

“I drove away and I thought, ‘Well, I didn’t say no, which means I’m seriously considering this.”’

The NDP’s slate in Tuesday’s election is 54 per cent female, beating the Alberta record the party set in 2015 when 52 per cent of its candidates were women.

The United Conservative Party had two women members of the legislature when the Progressive Conservatives and Wildrose merged in 2017. Twenty-seven — or 31 per cent — of its candidates in Tuesday’s election are women. That’s after two female candidates in Calgary resigned over past derogatory comments and were replaced by men.

The Alberta Party is running a 29 per cent female slate and 43 per cent of the candidates running for the Alberta Liberals are women.

Melanee Thomas, a University of Calgary political scientist who interviewed NDP organizers for research following the 2015 election, said leader Rachel Notley set a deliberate direction when it came to picking candidates.

Thomas suggested it’s no different this time around.

“They didn’t automatically say yes to whoever volunteered or showed the initial enthusiasm … They actually took time to do a candidate search to find people who are from historically underrepresented groups.”

Political scientist Lori Williams from Calgary’s Mount Royal University, said the United Conservatives have fewer women candidates in part because most constituencies had competitive nomination contests.

“Even if more women ran, not all of them won nominations.”

She also suggested left and centre parties tend to draw more women.

“It’s going to be harder to actually get equal numbers of nominees just because of that sort of traditionalism that tends to be associated with right-leaning parties, and particularly the UCP.”

Nicole Williams, the UCP candidate for Edmonton-West Henday, said she hopes more women run for and win future nominations.

“We need as many women to run for politics as possible, but I want to make sure that it’s based on the merit of what I’m doing.”

Williams has been to events held by She Leads, a group run by Rona Ambrose, a one-time federal Conservative cabinet minister, and Laureen Harper, wife of former prime minister Stephen Harper, to support small-c conservative women in politics.

The 34-year-old said she wasn’t outright recruited, but has been interested in conservative politics since she was 12 and was encouraged to run by friends, family and colleagues.

“It’s about talking to women who have the skills but maybe aren’t thinking that they’re quite ready for it or maybe aren’t aware that the opportunity is something that they should pursue,” said Williams.

Alberta Party contender Katherine O’Neill, 44, is running in Edmonton-Riverview, where her NDP and UCP rivals are also women. She recalls shrugging off repeated overtures to run for the Progressive Conservatives in 2015.

But then-premier Jim Prentice convinced her how valuable her perspective as a mother of young children would be at the table, she said. Most women politicians she knew of were older with grown kids.

O’Neill said the Alberta Party has a goal of having 50 per cent women. One way to achieve that, she suggested, is getting more women involved making decisions behind the scenes in political campaigns.

“You need a balance in both front of the house and back of the house.”