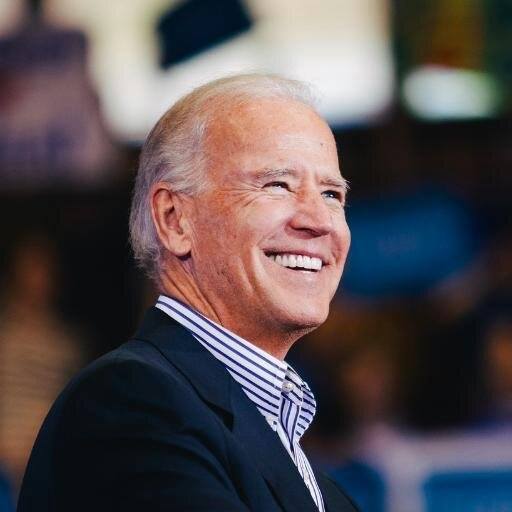

Joe Biden/Facebook)

COLUMBIA, S.C. — On the cusp of an expected White House run, Joe Biden is returning to a familiar role this week as the one of the nation’s top eulogists.

The former vice-president will speak Tuesday at the funeral of Fritz Hollings, the longtime South Carolina Democratic senator who was Biden’s Capitol Hill deskmate and friend. The tribute will add to the already memorable eulogies Biden has provided for everyone from Strom Thurmond to John McCain and Ted Kennedy, reflecting his status as the go-to man to speak about the legacies of Washington’s one-time titans.

But his presence at Hollings’ funeral also underscores Biden’s unique — and complicated — role in American politics in 2019. It’s a reminder of his decades-long presence on Capitol Hill at a time when some Democratic activists are putting a premium on fresh faces. And his relationships with Republicans, Democrats and one-time segregationists like Thurmond and Hollings come at a time when Democrats are placing greater emphasis on gender and racial diversity.

In the run-up to a widely expected presidential campaign, it’s these types of connections that Biden thinks make him stand out as a stabilizing figure in hyper-partisan times. But it’s also what could make him a hard sell to Democrats in a presidential primary.

Those close to him see eulogies like the one he’s slated to deliver on Tuesday as an example of the unifying role Biden can play in polarizing times.

“He grew up with these people. He learned from them, he came to become a leader with them,” said Matt Teper, Biden’s chief speechwriter in the first term of the Obama administration. “Republican or Democrat didn’t matter. They were all living it together.”

Politics aside, Biden is known as a poignant eulogist. Those close to him say that’s because he’s someone who has known profound grief following the 1972 car accident that killed his first wife and young daughter. That sorrow was compounded by the 2015 death of his son, Beau, a tragedy that weighed so heavily on Biden that he pointed to it as a reason not to seek the White House in 2016.

“There’s a politician way of delivering a eulogy, and a more human way of delivering a eulogy,” said Jon Favreau, a speechwriter for former President Barack Obama. “Joe Biden’s eulogies are as human as they come, and I suspect that he connects so well with people who are experiencing grief because he’s endured more than most.”

Biden acknowledged as much during a 2009 memorial service for Kennedy. The then-vice-president credited the longtime Democratic senator from Massachusetts for encouraging him to remain in politics following the car accident that claimed his wife and daughter.

“He crept into my heart, and before I knew it, he owned a piece of me,” Biden said. “I wouldn’t be standing here were it not for Teddy Kennedy. … He sort of took over the role of being my older brother.”

Biden has turned to eulogies to express appreciation for those who stood by him during difficult political moments. During his 2003 eulogy of Thurmond , a Democrat-turned-Republican who once ran for president as a Dixiecrat opposed to civil rights for African-Americans, Biden praised the senator as someone who stood by him during the confirmation battle of doomed Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork.

“Strom Thurmond stood by me when others didn’t and when it was against his political interest to do so,” Biden said. “When partisanship was a winning option, he chose friendship, and I’ll never forget him for it.”

In 1972, Biden entered the Senate with Jesse Helms, a North Carolina Republican who opposed civil rights legislation and once called the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “the single most dangerous piece of legislation ever introduced in the Congress.”

Although he didn’t eulogize the ultra-conservative Helms, Biden attended his funeral and spoke about him in a speech six months later. He also referenced Helms in a commencement address at Yale University, recounting how his perception of Helms changed once he came to know him on a personal level.

“It’s awful hard having to reach across the table and shake hands. No matter how bitterly you disagree, though, it is always possible if you question judgment and not motive,” Biden said.

He’s been more coy in remembering other Republicans. In his August remembrance of McCain , Biden noted that he and the Arizona Republican drew ire from both their caucuses by regularly sitting together in the chamber rather than with their partisans.

“My name’s Joe Biden. I’m a Democrat,” he said, sparking a chuckle from the audience in Phoenix before turning serious. “And I loved John McCain.”

Biden and his supporters see these moments as bipartisan flourishes, the type of overtures that could be helpful in appealing to white working class voters. And they’re not going away, even after he was roundly criticized recently for declaring his successor, Mike Pence, a “decent guy” despite his opposition to LGBT civil rights measures.

Last week, Biden called former Florida GOP Gov. Jeb Bush a “hell of a governor.”

But Biden allies say his nature is to make deeper connections with those around him.

Dick Harpootlian, a Democratic South Carolina state lawmaker who’s known and advised Biden for 40 years, said the former vice-president “was going to be friends with people he wanted to be friends with.”