OTTAWA — Canada’s chief electoral officer is “pretty confident” that Elections Canada has good safeguards to prevent cyberattacks from robbing Canadians of their right to vote in this year’s federal election.

But Stephane Perrault is worried that political parties aren’t so well equipped.

“They don’t have access to the resources we have access to,” Perrault said in an interview Monday, noting that “securing (computer) systems is quite expensive… Even the larger parties have nowhere near our resources and you’ve got much smaller parties with very little resources.”

Moreover, with thousands of volunteers involved in campaigns, he said it’s difficult to ensure no one falls prey to “fairly basic cyber tricks,” like phishing, that could inadvertently give hackers access to a party’s databases.

“You can spend a lot of money on those (security) systems and if the human (fails), that’s the weak link.”

Elections Canada has been training its own staff to resist such tricks and, along with Canada’s cyberspying agency, the Communications Security Establishment, will be meeting with party officials again next week to reinforce the need to train their volunteers.

Perrault said he was “really disappointed” that omnibus legislation to reform Canada’s election laws, passed just before Christmas, did not include measures to impose privacy rules on parties, which have amassed huge databases of personal information on voters. At the very least, he said, Canadians should be able to find out what information a party has collected on them and demand that it be revised or removed.

The legislation requires only that parties publish a policy for protecting personal information. There is no requirement to report a breach and no oversight by the privacy commissioner.

Should a party’s computer system be hacked and the information used to embarrass the party, as occurred to the Democrats during the 2016 U.S. presidential contest, Perrault said Elections Canada would have no role in investigating the matter.

That would be up to security authorities and the party involved. Under a “critical election incident protocol” announced last week, five senior bureaucrats would be empowered to decide when an incident is serious enough to warrant publicly disclosing it in the midst of a campaign.

Elections Canada would only be involved if a hacker used the information gleaned from a party’s databases to interfere with Canadians’ right to vote — for instance, by spreading disinformation about how, where and when they should vote.

“The important thing is that Canadians are not prevented from voting. From my perspective, that’s the No. 1 priority,” Perrault said.

In its own operations, Perrault said Elections Canada has done everything it can to prevent cyberattacks.

“Overall, I think we’re pretty confident we are where we need to be at this point.”

But he added: “It’s certainly uncharted territory for us. We’ve seen the Americans go through this and Brexit and France and Germany, so we have a sense of the potential out there. But we’ve never had to prepare for an election like this.”

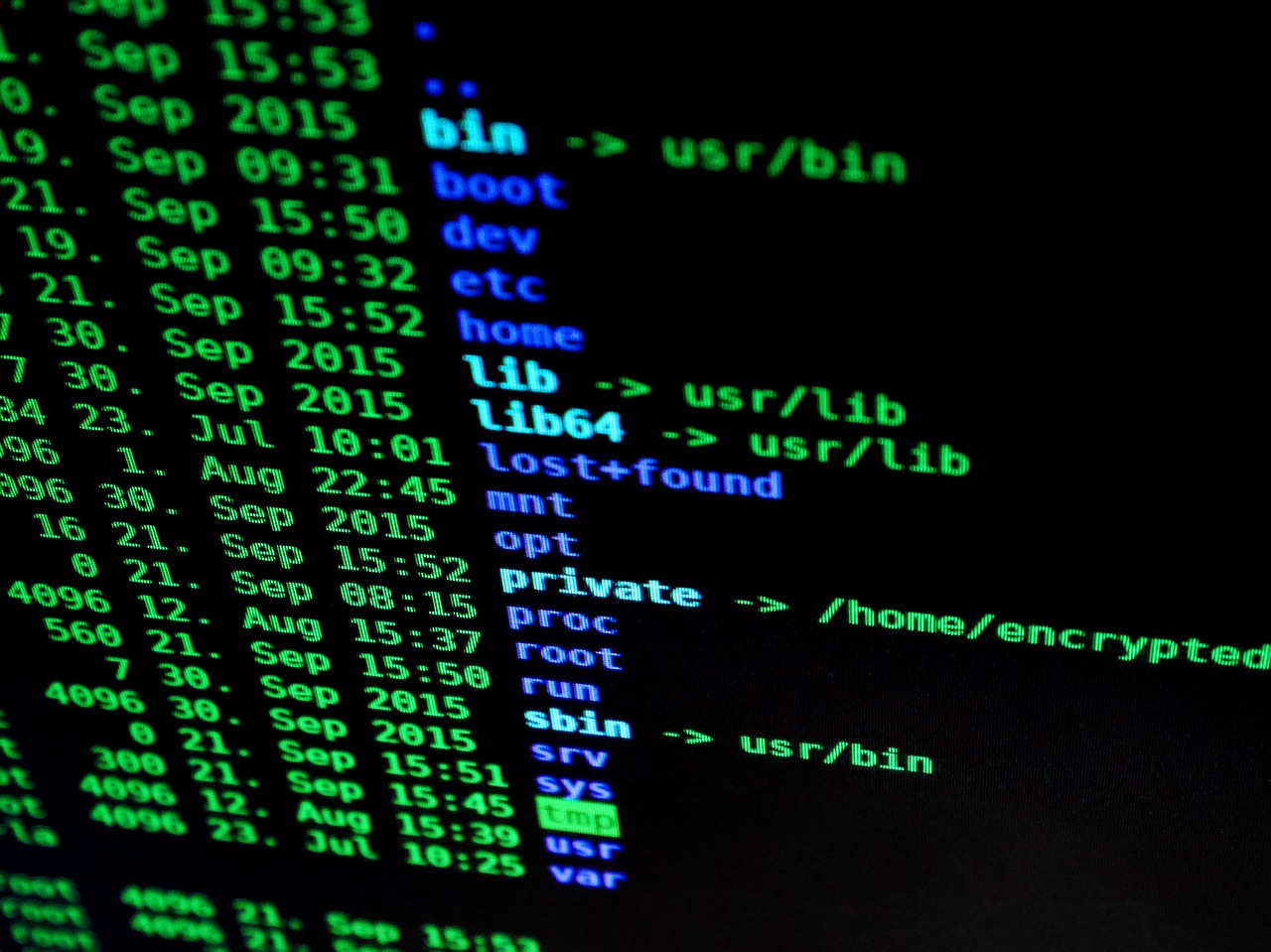

Since the 2015 election, Perrault said Elections Canada has rebuilt its information-technology infrastructure with sophisticated security improvements, based on advice from the Communications Security Establishment, which now monitors those systems 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“No system is 100-per-cent proof but they’re much more concerned about the parties than about Elections Canada,” Perrault said.

In addition, he said the agency has set up a team to monitor social media and to quickly counter any disinformation about the right to vote. As well, it will have a repository on its website of every public communication from Elections Canada so that individuals can verify the legitimacy of information they see on social media or elsewhere that purports to be from the agency.

“We really want to be the trusted source of information on the electoral process.”

The recently passed legislation included a number of measures aimed at preventing foreign interference and deliberate disinformation campaigns in Canadian elections, including giving the commissioner of elections greater powers to investigate and compel testimony, prohibiting the use of foreign money and requiring social-media giants to keep a registry of all political ads posted on their platforms.

But arguably the best hedge against cyberattacks is the fact that Canada still relies on paper ballots that are counted by hand.

“You can’t hack that,” Perrault said.