The U.S. still has tools to apply pressure on Maduro, even after years of tough rhetoric and increasing sanctions. But further targeted measures may do little to hurt the already-reeling South American country, and a major step like halting Venezuelan oil imports could damage the American economy. The most extreme step, direct military action, appears not to be under consideration, at least for now.

The U.S. and other nations on Wednesday took the highly unusual step of recognizing Juan Guaido, the opposition head of the National Assembly, as the interim president of Venezuela. Maduro, elected last year in a vote widely seen as fraudulent, still controls the military and security services and has support among at least a portion of the public. He’s given no sign that he intends to step down.

On Thursday, 16 of the 34 nations in the Organization of American States recognized Guaido at an emergency session. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urged members to oppose the “illegitimate” Maduro and pledged to make $20 million available for humanitarian assistance to the country.

“As a friend of the Venezuelan people, we stand ready to help them even more, to help them begin the process of rebuilding their country and their economy from the destruction wrought by the criminally incompetent and illegitimate Maduro regime,” he said.

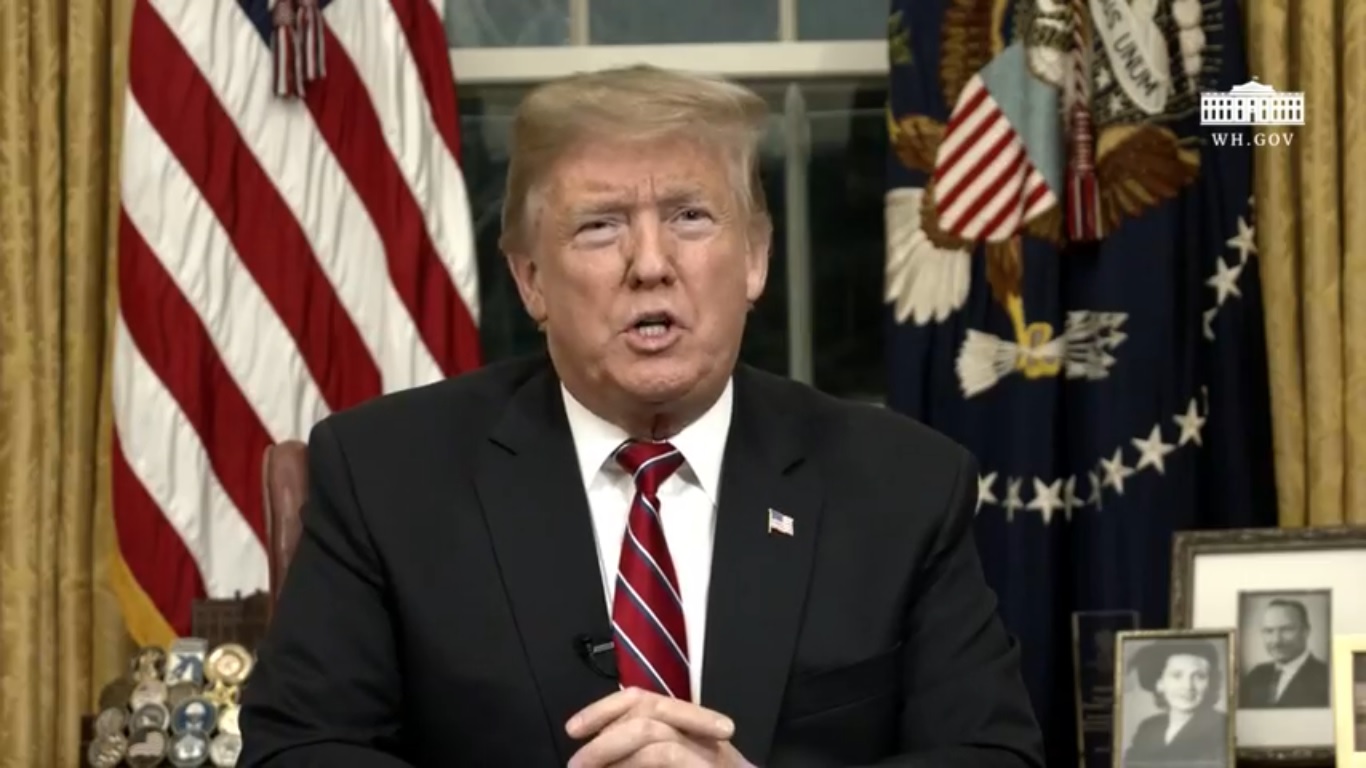

When asked about next steps, administration officials repeat variations of what the president said on Wednesday. “We’re not considering anything, but all options are on the table,” Trump told reporters, in response to a question about the possibility of military action.

A potent weapon called for by some lawmakers, including Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, would be sanctions on oil from Venezuela, the fourth largest supplier of crude to the U.S. But that could cause gas prices to rise, mean a loss of business for Gulf State refiners and have other ripple effects in the American economy.

“Sanctions on Venezuela’s energy sector would likely harm U.S. businesses, workers, and consumers while failing to address the very real issues in Venezuela,” Chet Thompson, president of the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, said in a letter to the president.

Another option to punish Venezuela would be to designate it a “state sponsor of terrorism,” which would impose wide-ranging sanctions and put strict limits on the ability of Venezuelan officials to travel to or within the United States. The administration has considered the measure but has for the moment ruled it out because Venezuela does not meet the legal criteria, which would include evidence that the government supported or ordered terrorist attacks.

Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, who represents thousands of Venezuelan expatriates in her South Florida district, favours “targeted” sanctions on the oil industry to reduce some of the money that flows to Maduro’s government. “That’s been something we held back because that obviously would have an economic impact on the U.S,” she said.

Wasserman Schultz doesn’t think a military solution is an option for resolving the political crisis. “I know the president is saying that all options are on the table and all means all, but I think a peaceful exit for Maduro needs to be the goal,” she said.

For the time being, Guaido is asking the U.S. to continue helping prevent Maduro and his associates from transferring wealth outside the country, according to an administration official, who was not authorized to publicly discuss the measure and spoke only on condition of anonymity.

National security adviser John Bolton said the Trump administration is focused on “disconnecting the illegitimate Maduro regime from the source of its revenues.” Those revenues should go to the legitimate government of Guaido, he said Thursday at the White House.

“It’s very complicated,” Bolton said. “We’re working really around the clock to do what we can to strengthen the new government.”

U.S. action will depend on what Maduro does next and whether the security forces respond violently to the opposition leader or his supporters, said Jason Marczak, director of the Atlantic Council’s Latin America centre.

Marczak said the U.S. could provide security assistance to help protect the new government, but there is no support among U.S. allies in the region for a military intervention.

“I think that would backfire if the U.S. unilaterally attempted to assert influence over the outcome of the situation because that would allow Maduro to pigeonhole opposition supporters as being aligned with the U.S.,” Marczak said.

Moises Rendon, associate director of the Americas program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said he sees no indication the Trump administration is considering military intervention. Maduro has ordered U.S. diplomats to leave the country. The U.S. has refused, saying it only recognizes the authority of Guaido, who urged diplomats to stay. On Thursday, the State Department ordered non-essential diplomats and staff at the U.S. Embassy in Caracas to leave the country, but said the embassy would remain open.

Rendon said the U.S. might be compelled to act if American diplomats in Caracas are in danger, but doubted there would otherwise be a military response. “I think this is only rhetoric,” he said.