ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Back-to-back earthquakes measuring 7.0 and 5.7 shattered highways and rocked buildings Friday morning in Anchorage, sending people running into the streets and briefly triggering a warning to residents in Kodiak to flee to higher ground for fear of a tsunami.

The warning was lifted without incident a short time later. There were no immediate reports of any deaths or serious injuries.

The U.S. Geological Survey said the first and more powerful quake was centred about 7 miles (12 kilometres) north of Anchorage, Alaska’s largest city, with a population of about 300,000. People ran from their offices or took cover under desks.

“It had my heart racing and I felt a bit of motion sickness afterwards. I was scared!” April Pearce wrote on Instagram after being shaken at her desk in the town of Soldotna.

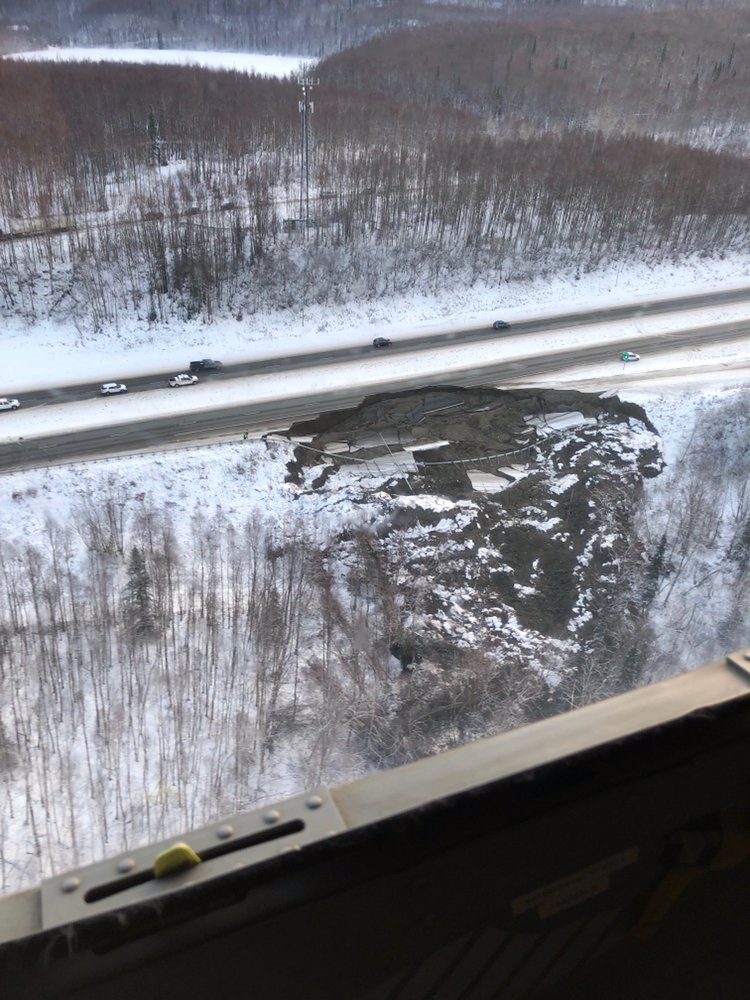

A large section of an off-ramp near the Anchorage airport collapsed, marooning a car on a narrow island of pavement surrounded by deep chasms in the concrete. Several cars crashed at a major intersection in Wasilla, north of Anchorage, during the shaking.

Anchorage Police Chief Justin Doll said he had been told that parts of the Glenn Highway, a scenic route that runs northeast out of the city past farms, mountains and glaciers, had “completely disappeared.”

The quake broke store windows, opened cracks in a two-story building downtown, disrupted electrical service and disabled traffic lights, snarling traffic. It also threw a full-grown man out of his bathtub.

All flights in and out of the airport were suspended for hours after the quake knocked out telephones and forced the evacuation of the control tower. And the 800-mile Alaska oil pipeline was shut down while crews were sent to inspect it for damage.

Anchorage’s school system cancelled classes and asked parents to pick up their children while it examined buildings for gas leaks or other damage.

Fifteen-year-old Sadie Blake and other members of the Homer High School wrestling team were at an Anchorage school gymnasium waiting for a tournament to start when the bleachers started rocking “like crazy” and the lights went out. People started running down the bleachers in the dark, trying to get out.

“It was a gym full of screams,” said team chaperone Ginny Grimes.

When it over, Sadie said, there was only one thing she could do: “I started crying.”

Jonathan Lettow was waiting with his 5-year-old daughter and other children for the school bus near their home in Wasilla when the quake struck. The children got on the ground while Lettow tried to keep them calm.

“It’s one of those things where in your head, you think, ‘OK, it’s going to stop,’ and you say that to yourself so many times in your head that finally you think, ‘OK, maybe this isn’t going to stop,”’ he said.

Soon after the shaking stopped, the school bus pulled up and the children boarded, but the driver stopped at a bridge and refused to go across because of deep cracks in the road, Lettow said.

Former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin tweeted that her home was damaged: “Our family is intact — house is not. I imagine that’s the case for many, many others.”

Officials opened an Anchorage convention centre as an emergency shelter. Gov. Bill Walker issued a disaster declaration.

Cereal boxes and packages of batteries littered the floor of a grocery store, and picture frames and mirrors were knocked from living room walls.

People went back inside after the first earthquake struck, but the 5.7 aftershock about five minutes later sent them running back into the streets. A series of smaller aftershocks followed.

A tsunami warning was issued along Alaska’s southern coast. Police in Kodiak, a city of 6,100 people on Kodiak Island, 250 miles (400 kilometres) south of Anchorage), warned residents to evacuate to higher ground immediately because a wave could hit within about 10 minutes.

Michael Burgy, a senior technician with the National Tsunami Warning Center in Palmer, Alaska, said the warning was automatically generated based on the quake’s size and proximity to shore. Scientists monitored gauges to see if the quake generated big waves. Because there were none, they cancelled the warning within about an hour and a half.

In Kenai, southwest of Anchorage, Brandon Slaton was alone at home and soaking in the bathtub when the earthquake struck. Slaton, who weighs 209 pounds, said it created a powerful back-and-forth sloshing that threw him out of the tub.

His 120-pound mastiff panicked and tried to run down the stairs, but the house was swaying so much that the dog was thrown off its feet and into a wall and tumbled to the base of the stairs, Slaton said.

Slaton ran into his son’s room after the shaking stopped and found his fish tank shattered and the fish on the floor, gasping for breath. He grabbed it and put it in another bowl.

“It was anarchy,” he said. “There’s no pictures left on the walls, there’s no power, there’s no fish tank left. Everything that’s not tied down is broke.”

Alaska was the site of the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the U.S. The 9.2-magnitude quake on March 27, 1964, was centred about 75 miles (120 kilometres) east of Anchorage. It and the tsunami it triggered claimed about 130 lives.

The state averages 40,000 earthquakes per year, with more large quakes than the 49 other states combined. Southern Alaska has a high risk of earthquakes because the Earth’s plates slide past each other under the region.

Alaska has been hit by a number of powerful quakes over 7.0 in recent decades, including a 7.9 last January southeast of Kodiak Island. But it is rare for a quake this big to strike so close such a heavily populated area.

David Harper was getting some coffee at a store when the low rumble began and intensified into something that sounded “like the building was just going to fall apart.” He ran for the exit with other patrons.

“People who were outside were actively hugging each other,” he said. “You could tell that it was a bad one.”

———

Associated Press writers Becky Bohrer in Juneau, Alaska; Mark Thiessen in Anchorage; Jennifer Kelleher in Honolulu; Gene Johnson in Seattle; Gillian Flaccus in Portland, Oregon; Rachel La Corte in Olympia, Washington; and John Antczak in Los Angeles contributed to this report.