YAOUNDE, Cameroon — Rudulf Arrey ventured out for a campaign rally the other day in Cameroon’s restive Southwest region, knowing the simple act of civic curiosity could kill him.

Separatists who declared an English-speaking state have threatened people who wander the streets, and so have government security forces who try to maintain order, the 24-year-old in Mamfe town told The Associated Press.

“If you are caught they may kill you,” he said of the separatists’ scattered, ragtag forces who have vowed to disrupt Sunday’s presidential election. Meanwhile, patrolling security personnel “at times … are very hostile to people around.”

Yet Arrey came out because he wanted to hear more about the ruling party’s vow: Longtime President Paul Biya, Africa’s oldest leader at 85, will be the one to solve the crisis.

The growing fight over language in an officially bilingual country has killed about 400 people and sent more than 200,000 people fleeing Cameroon’s Southwest and Northwest regions.

What began as protests two years ago by teachers and lawyers in the English-speaking regions against what they called the marginalization by majority French speakers turned deadly after the government cracked down. The separatists emerged, cheered on by some in Cameroon’s diaspora including the United States. But then fringe groups became violent.

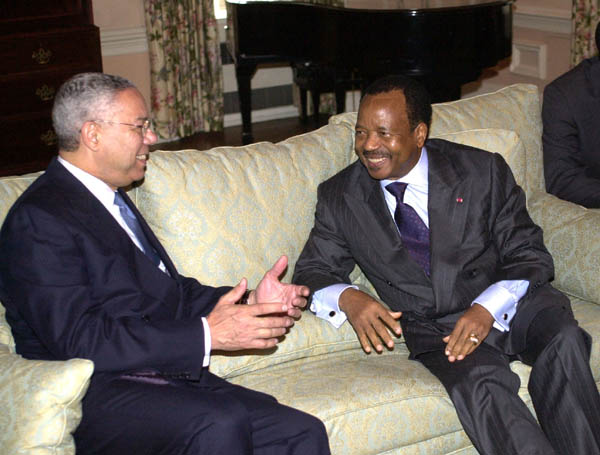

The result of Sunday’s election should be no surprise. The opposition hasn’t been able to rally around a challenger. Biya is expected to defeat his opponents easily and keep his grip on the office he entered in 1982.

But while 6.6 million people across Cameroon are registered to vote, the emptying streets in English-speaking regions point to a victory with a weakened mandate. One-fifth of the largely Francophone nation is English speakers, and many can no longer reach the polls.

The ruling Cameroon Peoples Democratic Movement has attempted to campaign as normal in the affected regions, holding several rallies, but Biya has never appeared. The party says at least eight of its officials have been abducted and some of its supporters attacked.

One exasperated opposition official, Mefire Ousmanou with the Cameroon Democratic Union party in the southwest, said the violence is increasing by the day.

Biya should open a dialogue instead of using force, he said. “The government should have encouraged reconciliation.”

The government insists the election will be peaceful throughout the country, and “those who try to organize chaos risk being disagreeably surprised,” spokesman Issa Tchiroma Bakary said on Twitter.

It’s a difficult promise to keep. The armed separatists, who number more than 1,000, reportedly have grown harsher over time. They once avoided targeting civilians but recently have been accused of attacking schools as well as anyone they suspect of giving information about them to security forces.

Casting a ballot is seen as taking a chance.

“Armed separatists have promised to disrupt the elections by all means. Even if they weren’t doing so, I’m not sure the majority of the Anglophone population will vote,” said Hans de Marie Heungoup, Central African senior analyst with the International Crisis Group. “While they do not support the violence taken on by armed separatists groups, they are more sympathetic to the ideology.”

Even if people want to vote, by law they must do it where they are registered. Many Cameroonians are now sheltering outside the affected regions in places like the nearly city of Douala.

Meanwhile more than 230,000 people are displaced in the country’s Far North region because of another security threat from Boko Haram extremists based in neighbouring Nigeria.

“Up to now the government and electoral body have not said clearly which means they will put in place for these people to vote,” Heungoup said. “There’s confusion.”

While the international community has urged what U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres calls “a peaceful, credible and inclusive process” on Sunday, major Western election observers such as the European Union will be absent.

Many of the remaining observers, including the African Union, have said they will not be carrying out their work in the troubled southwest and northwest because of the crisis.

———

Petesch reported from Dakar, Senegal.