MANAGUA, Nicaragua — Jairo Bonilla was inside a Managua seminary last spring during a break in Catholic Church-mediated talks to try to end Nicaragua’s bloody political crisis when two fellow students approached him with a threat.

“You’re going to pay,” warned one of them, Leonel Morales, the president of the government-backed student union at Nicaragua Polytechnic University, where they both studied. “Your family is going to cry tears of blood.”

“You know where to find me,” Bonilla replied.

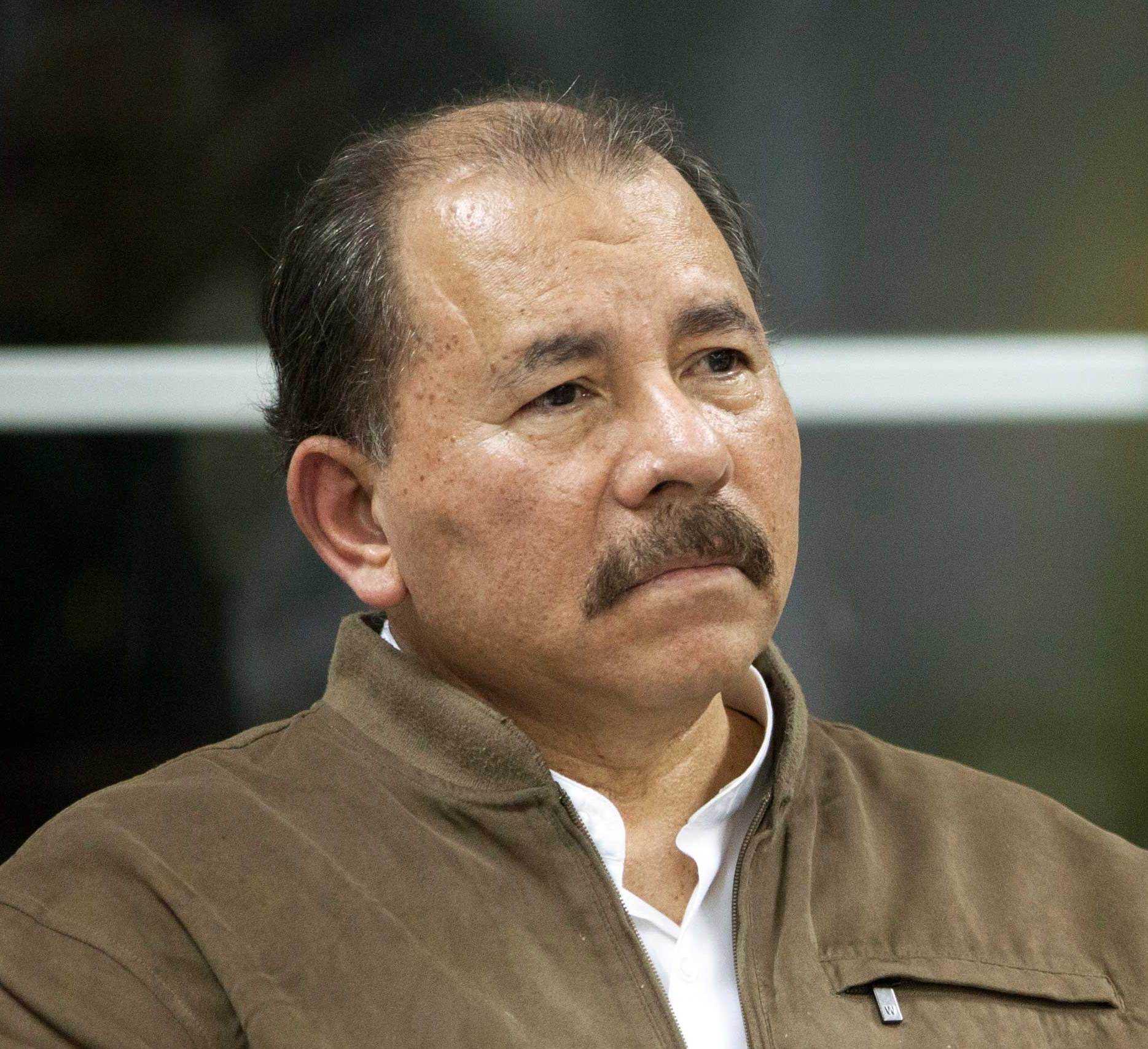

That was then. Now the 20-year-old, a leader of student protests against President Daniel Ortega’s government, is in hiding, trying to ignore the threats that come regularly on Facebook and in menacing text messages. He has survived four months of resistance to Ortega’s government, but the student movement he helps lead is now largely underground.

Hundreds of people have been killed in the government’s brutal suppression of the months-long protests that erupted in April. More than 2,000 people have been detained as security forces search for those who took part, including about 320 still in custody. Many say they have been abused at the hands of the authorities, including severe beatings and torture. The common refrain of “We’re not scared!” chanted at the early student marches, is seldom heard any more.

“Ortega achieved his objective,” Bonilla said in a recent interview, held at a secret location. “He made us feel fear.”

Chased off their college campuses, the future is uncertain for the students who have stood up to Ortega. Many have fled the country, others are scattered about in safe houses. Some are recovering from bullet wounds they suffered during the government crackdown or struggling with psychological trauma, while Bonilla and other student leaders try to rally the attention of the international community and strategize how to maintain pressure at home.

Bonilla joined the uprising against Ortega’s government in mid-April, angered like many of his classmates by the violent government response to protests by retirees angry over cuts in social security benefits. After the marches quickly evolved into a general call for Ortega’s ouster and student casualties mounted, Bonilla volunteered to represent his fellow students in the church-mediated talks to try to end the crisis.

That effort was short-lived. In a fiery speech in July, Ortega accused the Roman Catholic bishops organizing the mediation of being “coup mongers” seeking his ouster and said they were unqualified to be mediators. The talks have not restarted.

With control of the country’s universities and other opposition bastions now firmly in government hands, Ortega, who has been in power since 2007, has vowed to remain in office until at least 2021, when his latest term ends. He has dismissed those who participated in the protests as “terrorists” manipulated by outside forces.

These days, Bonilla spends his time holed up in his hideout, trying to prepare for the day when talks with the government might resume. He reads political economy texts, studies negotiation tactics and absorbs as much as he can about Nicaraguan history online. He has changed safe houses twice since June.

Still, Bonilla’s situation is better than some.

He is still in Nicaragua and slips out in the open, his face masked by a bandanna, to participate in the sporadic, smaller protest marches that continue despite the arrests and mounting death toll. Other students were locked up for days in a shed or forced to hide at the bottom of a well while government forces searched for them.

There is now a tense calm in Managua, following the violent government crackdown. The stone barricades the students and other government opponents erected at the height of the protests on major highways and outside entire neighbourhoods have now been removed by government forces. But there is little activity after nightfall; many restaurants are shuttered and people rush home at dusk, fearful of the masked armed civilians working in co-ordination with the police who patrol the city’s streets.

In the moments when they aren’t worried about being discovered or where their next meal will come from, many of those in hiding grow despondent over an unraveling future.

“We want to go on with our normal lives,” Bonilla said.

One 25-year-old woman, who had been working on a master’s degree at the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua before she joined the student resistance movement, is already in her second country of exile. Early this month, she fled to Costa Rica, where she had hoped to establish a network of support for those in hiding in Nicaragua. But rumours of government informants among the Nicaraguan exile community there forced her to take off again. Now she is in a third Central American country.

“I don’t see my future,” said the woman, speaking on condition of anonymity because she hopes to return to Nicaragua one day. “I had planned this year to start classes to finish (the degree), but now I’m directionless.”

Among those in hiding in the Nicaraguan capital is a 20-year-old former student at the national university who lost much of the mobility in his right arm and hand after being shot by security forces on June 23 while helping treat wounded students as they came under fire.

The bullet entered his side and lodged behind his shoulder blade, requiring extensive surgery. He was hospitalized for 11 days and suffered nerve damage, but doctors tell him he could recover with a few months of intensive physical therapy.

Instead he’s in a safe house with his 18-year-old brother, who is also in hiding. Both declined to be identified for fear of arrest.

The younger brother said they struggle to sleep, listening to passing traffic and thinking that at any moment they could be discovered.

“All of us who were there in the struggle, they know us,” he said of the security forces.

“Since the moment that we decided to join the struggle we all knew that a time would come when we would be pursued,” he said. “And in case the struggle isn’t won and the regime stays in place, I believe that will basically be the end of our lives. Because we won’t be able to return to the university, we won’t be able to walk in the street.”

Hugo Torres, a guerrilla commander who once fought with Ortega during Nicaragua’s 1979 revolution and a retired general with the Nicaraguan army, said it’s natural that students who haven’t experienced such a struggle before would see a darker and suddenly more complicated future for themselves.

“These struggles have their flows, like the tide, their ebbs,” said Torres, who broke with Ortega two decades ago and now is vice-president of the opposition Sandinista Renovation Movement. There is time to mourn the dead, he said, but that doesn’t mean “your spirit falls or you give up the fight.”

“Nicaragua’s history is one of civil wars with small intervals of peace,” Torres said. “We’re obligated to break this cycle.”

Bonilla agrees.

“We’re scared of being massacred, of being arrested, but if that is the price we have to pay, we’re going to do it for a free Nicaragua.”