OTTAWA — Experience usually helps when it comes to getting a job — except, it seems, when that job is at the helm of the Assembly of First Nations, where experience often seems more of a liability than an asset.

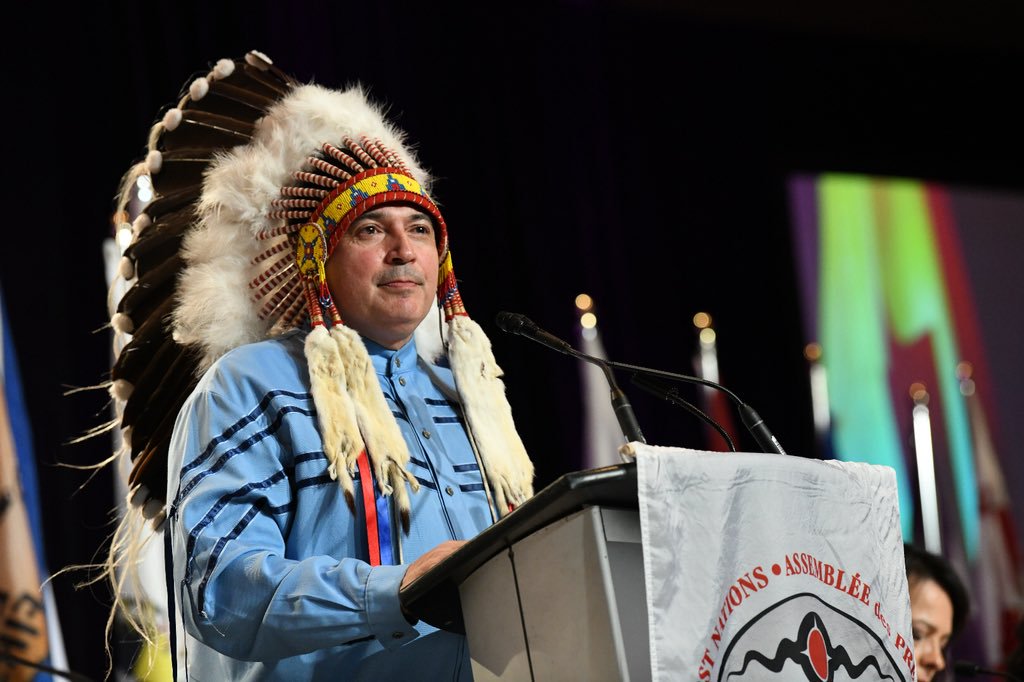

Just ask Perry Bellegarde, the incumbent national chief of Canada’s most powerful Indigenous organization, who after three years in the role has rivals accusing him of being too chummy with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Liberal government.

“Every national chief gets accused of being too close to the prime minister, to government,” Bellegarde said in a recent interview.

“We have to have a relationship with policy and legislative decision-makers.”

Maybe so, but as Bellegarde knows all too well, that relationship will be a major issue for him as the race to lead the AFN gets underway officially today. Candidates need the support of 15 chiefs representing First Nations communities, including eight from outside the candidate’s province or territory.

At least two of Bellegarde’s opponents are taking aim at his relationship with Trudeau, saying the fundamental role of the national advocacy organization has to change.

“The national chief in my view has been so cosy with the government he hasn’t allowed any critical analysis of anything that’s happened,” said candidate Russell Diabo.

As examples, Diabo cites the federal government’s decision to split Indigenous Affairs into two separate departments, one focused on services, the other on Indigenous-Crown relations, as well as the government’s much-maligned legal framework for Indigenous rights.

Sheila North, grand chief of the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, said she wants the AFN to “quit acting like a government.”

“The current AFN leader right now — he’s campaigning and celebrating the accomplishments of the federal government, and he’s taking them as his own,” said North, a former journalist.

“There’s no mention of things that need to change for our people and our communities to see greater opportunities. It’s like he’s happy with how our lives are right now and I don’t think he should be.”

Chiefs from 634 First Nations communities will elect a new national chief to a three-year term on July 25 in Vancouver. Two other candidates, Katherine Whitecloud and Miles Richardson, have also announced their intention to run, but could not be reached for an interview.

Diabo, a member of the Mohawk Nation at Kahnawake, also took aim at a government that he sees as “a threat to our rights.”

The government, he said, has acted in secret and unilaterally when it comes to ongoing efforts to come up with a new Indigenous legal framework, and consults only chiefs when it goes in search of input from Indigenous communities.

In February, Trudeau vowed to develop a “recognition and implementation of Indigenous rights framework” to guide all of the government’s interactions with Indigenous Peoples, with new legislation meant to be introduced and implemented before next year’s federal election.

Trudeau said the government would develop the framework in partnership with First Nations, Inuit and Metis people, and that it would include new ways to recognize and implement Indigenous rights, part of an effort to get away from the outdated and oft-criticized Indian Act.

“In terms of self-determination and decision-making of the people, there needs to be forums developed to get out of the Indian Act through plans developed by each community, not legislated through Parliament,” said Diabo.

And he wants to see the government “stop what they’re doing” and start a process that involves all First Nations communities.

“There’s widespread discontent with the AFN and often with their own chiefs and councils because 1/8people 3/8 feel they’re not involved in the decision making of these agreements that are being signed.”

Bellegarde, meanwhile, remains focused on the money he says he’s managed to secure from the government, Diabo said.

“There is that thinking … let’s just go along with this government because the Harper government starved us out for 10 years, so let’s go for the money that’s being offered. But the problem is that money’s being offered in a context that’s not being analyzed by AFN properly.”

Although he dismissed criticism of his relationship with Trudeau, Bellegarde admits there’s been a “big change” between Trudeau’s government and the previous one.

“It was pretty tough four years ago,” he said.

“I think the First Nations leaders and people across Canada are seeing the relevancy of the AFN when we can say, ‘Look, $17 billion.’ That’s pretty effective advocacy.”

Bellegarde said he was successful in putting his organization’s “Closing the Gap” document in front of every party during the 2015 election with the message that if they wanted to be elected, First Nations priorities would have to be part of their platform.

“That’s the lobbying. That’s the advocacy,” he said, citing the inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls as well as Trudeau’s multiple speeches before the assembly as evidence of its success.

And when it comes to charges that the fortunes of the two leaders are linked, Bellegarde is having none of it.

“I’m not in anybody’s camp. I’m in the First Nations camp,” he said.

“It’s all about the implementation of Aboriginal rights and title and treaty rights and getting investments, long-term sustainable investments, to close this gap. That’s what it’s all about.”