ALEPPO, Syria — Aleppo’s largest square was packed with people of all ages: young men performing a folk dance, children playing, others buying ice cream, popcorn, peanuts and salted pumpkin seeds. A giant sign spells out in colorful English letters, “I love Aleppo.”

The scene in Saadallah al-Jabiri Square on a recent day was a complete turnaround from what it was during nearly four years of warfare that wracked the Syrian city. Rebel sniper fire and shelling — and a triple car bombing that killed dozens — made it a no-go zone. For much of the fighting, the square stood near the front line dividing the government-held western half of Aleppo from the rebel-held eastern half.

Thirteen months after government forces captured the east, crushing rebels, there have been some improvements in Aleppo. The guns are silent, allowing life to return to the streets. Water and electricity networks are improving. But the city has barely begun to recover from devastation so great and a civilian flight so big that residents find it difficult to imagine it could ever return to what it was.

Aleppo’s eastern half remains in ruins. Its streets have been cleared of rubble but there’s been little rebuilding of the blocks of destroyed or badly damaged buildings. Though some residents have trickled back, hundreds of thousands still have not returned to their homes in the east, either because their homes are wrecked or because they fear reprisals for their opposition loyalties.

Also, after the victory by the forces of President Bashar Assad, there’s little sign of attempts at reconciliation in Syria’s largest city or talk of how part of the city rose up trying to bring down Assad’s rule. To reporters, residents — whether out of genuine sentiment or fear of state reprisals — express only pro-Assad sentiment and dismiss the rebels as Islamic militants backed by foreign powers. Die-hard opposition sympathizers likely have not returned or keep it to themselves, and everyone is more focused on grappling with the destruction in the city.

“I feel very sad, I cry. Sometimes I cry in the morning because this was a very good neighbourhood,” said Adnan Sabbagh, standing on a balcony in his building in the once rebel-held eastern district of Sukkari.

The view from his balcony is a landscape of wreckage. Across the street is a pile of rubble a block long that used to be the Ein Jalout school compound that his three daughters and two sons once attended. Beyond it stand apartment buildings that have been sheared in half, their internal staircases jutting out exposed. The building adjacent to Sabbagh’s has been levelled to a hill of broken concrete, rebar and stone.

Sabbagh’s own six-story building still stands but the top three floors have had all their walls blasted away, leaving slabs of concrete floor dangling precariously.

The 47-year-old construction worker fled to live in the coastal town of Jableh five years ago as soon as the rebels overran Aleppo’s east. All three of his daughters are married to soldiers in Assad’s army, so he feared the fighters would not tolerate his presence.

In the autumn of last year, he returned home and fixed up his apartment on the second floor where he now lives with his wife and youngest son, Hamza. He relies on generators set up in the neighbourhood because like most other parts of east Aleppo, there’s no electricity in Sukkari — the government is still working to reinstall electricity poles. But running water has been restored — though it’s available only every other day, as is the case throughout the city east and west.

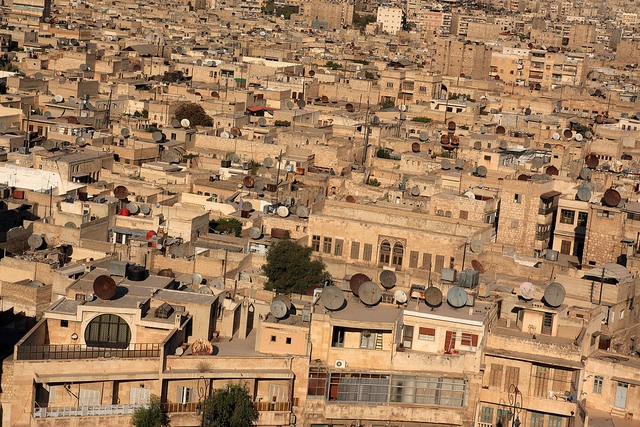

Aleppo, with a pre-war population of 2.3 million, was Syria’s largest city and its commercial centre. More than that, it was a culture all its own within Syria. Aleppans take enormous pride in their own accent of Syrian Arabic and their city’s famed cuisine with its own styles of roast meats and mezze appetizers. The city’s history spans millennia, and tourists were drawn by its historic citadel, Ummayad Mosque and covered bazaar.

But it became one of the most vicious battlegrounds of Syria’s still ongoing war.

In July 2012, rebels stormed eastern parts of the city where they found a welcome among many of its poorer residents. For the next few years, the opposition fighting Assad around the country saw their enclave in Aleppo as the jewel of their uprising, their strongest urban centre. It tore Aleppo in two, however, with destructive battles between the two halves as tens of thousands fled the city.

In 2016, government forces backed by Russian airstrikes surrounded the enclave, besieging it for months, pounding it with barrages. By the end, the rebels and residents trapped with them in a shrinking area of neighbourhoods faced either being crushed or starving. In December 2016, they surrendered. The rebels were sent to opposition territory elsewhere, while the few remaining residents were evacuated, leaving the eastern sector — once home to well over 1 million people — a shattered, empty shell.

Since then, some have filtered back. The top U.N. official in Syria, Ali Al-Za’tari, said the numbers are uncertain but that the U.N is aware of close to 200,000 now living in the east, based on those who have registered for assistance.

Most of the factories in Aleppo’s 15 industrial districts are still closed, many of them damaged either from looting or from bombardment by government forces when they were held by rebels. Despite the relative peace, insurgents on Aleppo’s western outskirts fire shells occasionally. That has slowed the return of production at Lairamoun, an industrial district only few hundred meters (yards) from rebel positions.

Ghassan Nazi, owner of a textile factory in Lairamoun, said that once the rebels are pushed back, he will reopen his business. Touring the now silent factory, he said it was used as a prison by an Islamist rebel faction called the Badr Martyrs. He said he’s suffered some $5 million in losses.

He blames everything that tore apart his city on “neighbouring countries” that he said plotted to destroy Aleppo as an economic engine. He didn’t say which countries but many government supporters use the phrase to refer to opposition-backer Turkey. “They simply want to turn us from producers to consumers,” he said.

In western Aleppo, where damage was much less, there’s a feeling of liberation from life under warfare. Power comes several hours a day and will soon run around the clock. Sand berms that had been set up on many streets have been removed, and security checkpoints have been pulled from the heart of the city to its entrances, freeing traffic.

Im el-Nour, a 51-year-old woman who drives a taxi — the only female cab driver in the city, she says — has seen a boost in work. She can now operate in the east, where conservative women call her for their errands to avoid riding with a male driver. El-Nour also works as a DJ at women-only parties or weddings, which have become more frequent now with the relative peace.

“One of the songs that I play a lot is Cheb Khaled’s Cest La Vie,” she said, referring to a popular Algerian singer. She added that Aleppo’s women also like to dance to Canadian singer Celine Dion, Shakira and Lebanon’s Najwa Karam.

Between her two jobs, el-Nour — who is divorced and who lost a son, killed while fighting as a soldier in Assad’s army — makes more than $100 a month, a bit more than a typical civil servant’s salary. “Aleppo will again become the jewel of the Middle East,” she boasted.

At Saadallah al-Jabiri Square, Mustafa Khodor churned out popcorn as parents lined up to buy from him. He said his sales have tripled. “The liberation of Aleppo was a turning point for us in this city. People now feel safe and go out,” said the father of five.

Nearby, Abdullatif Maslawi, a 21-year-old law student, performed a traditional dance known as dabke with a group of his friends.

“Aleppo is my soul,” he said. “Aleppo was wounded and now it is being cured.”