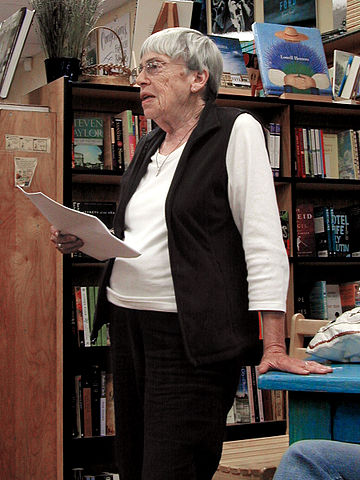

PORTLAND, Ore. — Ursula K. Le Guin, the award-winning science fiction and fantasy writer who explored feminist themes and was best known for her Earthsea books, has died at 88.

Le Guin died suddenly and peacefully Monday at her home in Portland, Oregon, after several weeks of health concerns, her son, Theo Downes-Le Guin said Tuesday.

“She left an extraordinary legacy as an artist and as an advocate of peace and critical thinking and fairness, and she was a great mother and wife as well,” he said.

“Godspeed into the galaxy,” Stephen King tweeted, saying Le Guin was a literary icon, not just a science fiction writer.

Le Guin won an honorary National Book Award in 2014 and warned in her acceptance speech against letting profit define what is considered good literature.

Despite being a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1997 — a rare achievement for a science fiction-fantasy writer — she often criticized the “commercial machinery of bestsellerdom and prizedom.”

“I really don’t want to watch American literature get sold down the river,” Le Guin said in the speech. “We who live by writing and publishing want — and should demand — our fair share of the proceeds. But the name of our beautiful reward is not profit. Its name is freedom.”

Le Guin’s first novel was “Rocannon’s World” in 1966 but she gained fame three years later with “The Left Hand of Darkness,” which won the Hugo and Nebula awards — top science fiction prizes — and conjures a radical change in gender roles well before the rise of the transgender community.

The book imagines a future society in which people are equally male and female and also dramatizes the perils of tyranny, violence and conformity.

Her best-known works, the Earthsea books, have sold in the millions worldwide and have been translated into 16 languages. She also produced volumes of short stories, poetry, essays and literature for young adults.

Le Guin’s work also won the Newbery Medal, the top honour for American children’s literature. Last year, she was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

“I know that I am always called ‘the sci-fi writer.’ Everybody wants to stick me into that one box, while I really live in several boxes,” she told reviewer Mark Wilson of Scifi.com.

Neil Gaiman, a fellow Newbery, Hugo and Nebula recipient, mourned her death on Twitter and called Le Guin “the deepest and smartest of the writers.”

“Her words are always with us. Some of them are written on my soul,” he wrote.

A longtime feminist, Le Guin earned degrees from Radcliffe and Columbia. Her 1983 “Left-Handed Commencement Address” at Mills College was ranked one of the top 100 speeches of the 20th century in a 1999 survey by researchers at the University of Wisconsin and Texas A&M University.

“Why should a free woman with a college education either fight Machoman or serve him?” she told the graduates. “Why should she live her life on his terms? … I hope you live without the need to dominate, and without the need to be dominated.”

Born in Berkeley, California, on Oct. 21, 1929, Le Guin described a well-off childhood even during the Depression, with summers in the countryside. Her success followed an early setback: At age 11, she had her first offering rejected by Amazing Stories, the pioneering science fiction magazine.

“During the Second World War, my brothers all went into service and the summers in the Valley became lonely ones, just me and my parents in the old house,” she told sfsite.com, another science fiction website.

“There was no TV then; we turned on the radio once a day to get the war news. Those summers of solitude and silence, a teenager wandering the hills on my own, no company, ‘nothing to do,’ were very important to me. I think I started making my soul then,” she said.

She married Charles Le Guin in Paris in 1953. They moved to Portland and had three children.

Her themes ranged from children’s literature to explorations of Taoism, feminism, anarchy, psychology and sociology to tales of a society where reading and writing are punishable by death and of a scientist who battles aliens to save the world.

Critic Harold Bloom placed her in the pantheon of fantasy writers along with JRR Tolkien.

“Sometimes I think I am just trying to superstitiously avert evil by talking about it,” she told sfsite.com. “Throughout my whole adult life, I have watched us blighting our world irrevocably … ignoring every warning and neglecting every benevolent alternative in pursuit of ‘growth.”’