FAYETTEVILLE, N.C. — When Veronica was raped more than 13 years ago, she says neither the police nor the hospital staff believed her story that a longtime friend attacked her while his mother was in the next room.

“I was treated like a female crying wolf,” said Veronica, who says the man raped her while she was unconscious. She believes he drugged her drink.

She was surprised, earlier this year, when she got a call from the initial investigating officer, John Somerindyke, who apologized for how she was treated and for something that Veronica didn’t yet know: Her rape kit was among 333 kits that Fayetteville police had thrown away.

Years after the kits were discarded, Fayetteville police began working with a crisis group to call the victims and tell them what happened.

The Joyful Heart Foundation, which works to end the backlogs, says Fayetteville police may stand alone in the effort to contact survivors about trashed rape kits. “I don’t know of any others that have taken it on like Fayetteville has by apologizing to survivors and to communities and trying to do what they can to fix it,” said Ilse Knecht, director of advocacy and policy for the foundation, founded by actress Mariska Hargitay.

Backlogs of untested rape kits have surfaced as a problem at police departments around the country. The foundation knows of at least 200,000 untested rape kits nationwide, Knecht said.

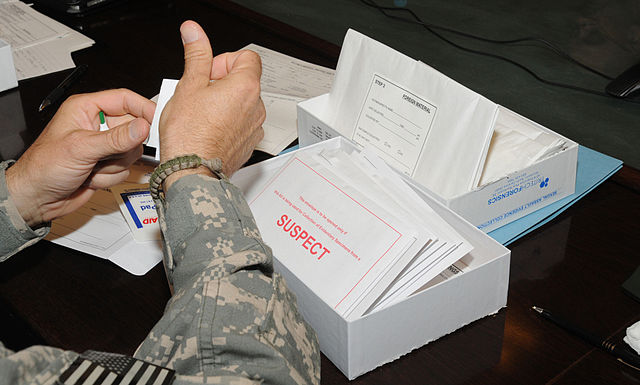

The kits, about the size of a shoe box, had been collected in Fayetteville between 1995 and 2008. Police began throwing them away in 1999 to make space in the evidence room. Somerindyke, now a lieutenant, discovered the kits were missing in February 2015 when he reviewed unsolved rape cases.

Of the 333 destroyed kits, 52 belonged to women whose cases had resulted in arrests, leaving 281 survivors with unsolved cases and no rape kits as evidence. Instead of simply moving on and vowing to do better in the future, the Fayetteville Police Department announced what happened and then called victims individually, including those cases in which arrests had been made.

“We felt it was the right thing to come forward,” Somerindyke said. “We felt like they had the right to know what had happened to their kit.”

The department enlisted the help of Rape Crisis Volunteers of Cumberland County, which got grant money and hired a victim’s advocate to make the calls. The advocate, Danielle Sgro, said victims’ responses ran the gamut. Some were angry or sad their kits were destroyed and said the calls stirred up memories they’d pushed aside. But others were grateful that someone cared enough to call.

Veronica, who agreed to let the AP use her first name, but not her last, said she’s among the grateful ones. The Associated Press doesn’t typically publish names of sexual-assault victims.

“There was an apology for things not being handled how they should have been,” said Veronica, 34, who joined the Air Force after her attack and moved around the country before settling in Fayetteville again. “He (Somerindyke) was interested in rectifying that as much as possible in the now. That’s beyond appreciated.”

In 90 per cent of the cases involving the destroyed rape kits, someone was reached or the victim was no longer living, Somerindyke said.

Gathering evidence for a rape kit “is a humiliating, long, traumatic experience,” said Deanne Gerdes, executive director of Rape Crisis Volunteers. But she finds the response of the Fayetteville Police Department heartening.

“It happened. The kits were thrown away,” she said. “But the Fayetteville Police Department is now doing something about it. … If you reached out to any other jurisdiction, if they were honest, they would say yes, we have kits sitting on the shelf or yes, we threw kits away.”

Somerindyke said, “We could have and should have done better.”

Since 2009, it’s been illegal in North Carolina to destroy a rape kit. And by Jan. 1, law enforcement agencies must report the number of untested rape kits in their possession to the State Crime Laboratory.

Veronica had been friends with her attacker for years when she went with him in June 2004 to the home he shared with his mother and drank part of an alcoholic beverage that she’s certain was laced with something that knocked her out. She woke up on his bed “and I knew I had been violated,” she said.

She escaped the house, and friends took her to a hospital. Veronica recalls that during the original investigation, Somerindyke seemed like he was just going through the motions. But when he called to tell her about the destroyed rape kit, “I didn’t know it was the same guy at all,” Veronica said. “He had a very genuine heartfelt interest in righting wrongs.”

Police reopened Veronica’s case, but without the rape kit, the district attorney declined to prosecute, Somerindyke said. However, the man whom she identified as her rapist is now behind bars on a murder charge. She plans to attend his trial and hopes to see her attacker sentenced to many years behind bars.

But the rest of the saga that began more than 13 years ago is behind her. “I don’t feel like a victim or a survivor,” she said. “I feel like a warrior.”