Baltimore has set a new per-capita homicide record as gunmen killed for drugs, cash, payback – or no apparent reason at all.

A surge of homicides in the starkly divided city resulted in 343 killings in 2017, bringing the annual homicide rate to its highest ever – roughly 56 killings per 100,000 people. Baltimore, which has shrunk over decades, currently has about 615,000 inhabitants.

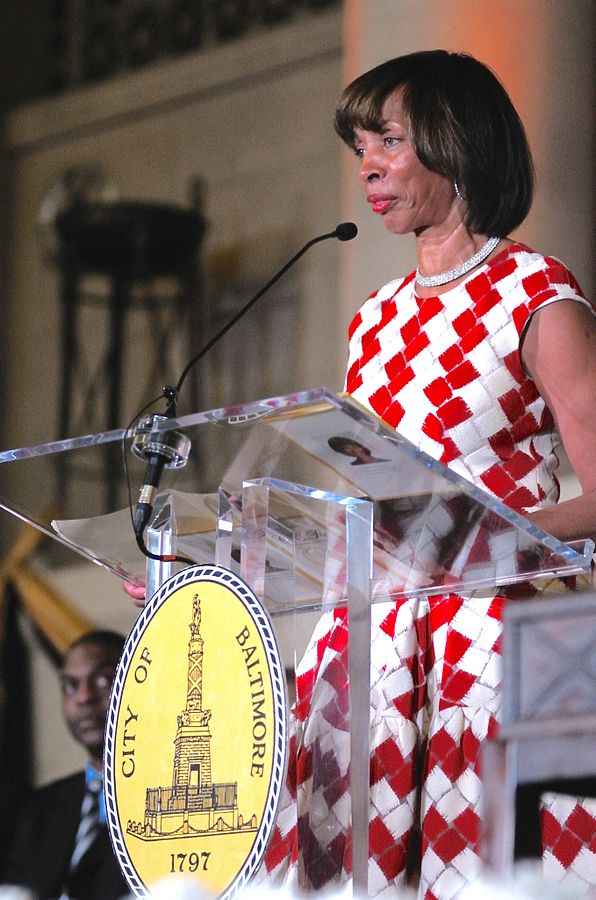

“Not only is it disheartening, it’s painful,” Mayor Catherine Pugh told The Associated Press during the final days of 2017, her first year in office.

The main reasons are the subject of endless interpretation. Some attribute the increase to more illegal guns, the fallout of the opioid epidemic, or systemic failures like unequal justice and a scarcity of decent opportunities for many citizens. The tourism-focused Inner Harbor and prosperous neighbourhoods such as Canton and Mount Vernon are a world away from large sections of the city hobbled by generational poverty.

Others blame police, accusing them of taking a hands-off approach to fighting crime since six officers were charged in connection with the 2015 death of Freddie Gray, a black man whose fatal spinal cord injury in police custody triggered massive protests that year and the city’s worst riots in decades.

“The conventional wisdom, or widely agreed upon speculation, suggests thatthe great increase in murders is happening partly because the police have withdrawn from aggressively addressing crime in the city’s many poor, crime-ridden neighbourhoods,” said Donald Norris, professor emeritus of public policy at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

Even as arrests have declined to their lowest level in years, police say their officers are working hard in a tough environment. They note the overwhelming majority of Baltimore’s crime has long been linked to gangs, drugs and illegal guns.

“The vast majority of our kids and residents of this city aren’t into criminal activity like this. It’s that same revolving group of bad guys that are wreaking havoc for people’s families,” said T.J. Smith, the chief police spokesman whose own younger brother was the city’s 173rd homicide victim in 2017.

Baltimore’s homicide rate started to surge after Gray’s death in 2015, a year when the city saw over 340 slayings. There’s been a depressingly steady march of killings since.

Violent crime rates in Baltimore have been notoriously high for decades and some locals sardonically refer to their city as “Bodymore” due to the annual body count. But prior to 2015, Baltimore’s killings had generally been on the decline. Before rates in recent years eclipsed it, Baltimore’s homicide rate had peaked with 353 killings in 1993, or some 49 killings per 100,000 people. Baltimore had over 700,000 inhabitants back then, making the per-capita rate lower than in 2017.

Patrick Sharkey, a sociologist at New York University, described Baltimore as a place “where there is an urgent need to make sure that neighbourhoods do not continue to fall apart and the population doesn’t give up on the city.”

Pugh, who took officeas mayor in December 2016, said her year-old administration is focused on reducing crime, boosting police recruits, and improving long-neglected neighbourhoods. She told attendees at a candlelight vigil she hosted for victims of violence that “this will become the safest city in America.”

Attending the vigil were Norman and Yvonne Armstrong, who struggled for words to describe their heartache since losing their son, Shawn, to gun violence. The working family man, a 31-year-old father of three, was fatally shot at a Baltimore carwash in September. His murder is unsolved.

“The kids out there with guns don’t care about anything,” said Norman Armstrong, the pain of grief etched on his face.

Among the names behind the 2017 numbers is Jonathan Tobash, a 19-year-old college student who embodied the best hopes of his Baltimore community. Police say the sophomore at Morgan State University was shot to death Dec. 18 after stumbling onto a robbery in progress outside a convenience store near his family’s home.

Ericka Alston-Buck, who founded the Kids Safe Zone community centre in the rough Sandtown-Winchester neighbourhood, said concentrated poverty must be addressed and a measure of healing has to take place in order to truly tackle high rates of violence in Baltimore.

“Hurt people hurt people. No one’s doing anything to close those holes in their souls,” she said. “As long as no one does that, nothing is going to change.”