Ottawa has set aside nearly 60 square kilometres of seabed off the coast of Nunavut to keep gawkers and scavengers away from one of Canada’s most famous shipwrecks.

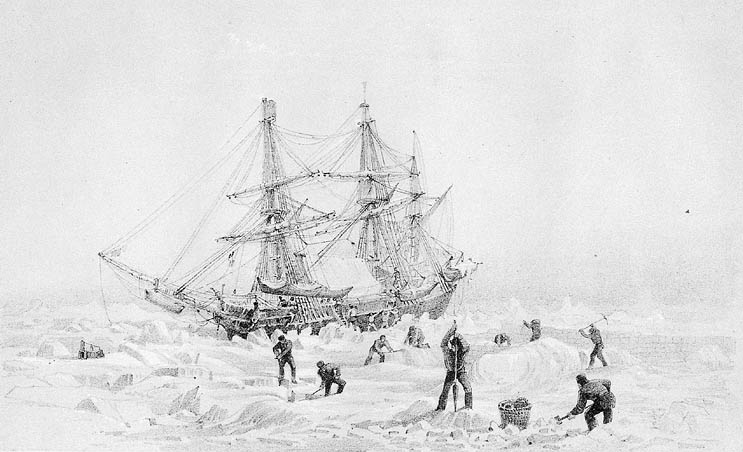

The HMS Terror is one of two ships from the Franklin expedition which became trapped in ice in the Arctic in 1845, ultimately leading to the deaths of all 129 men on board, including expedition leader Sir John Franklin.

The location of the wrecked ships were one of Canada’s greatest unsolved mysteries until September 2014, when the first of the two ships, the HMS Erebus was found south of King William Island.

The HMS Terror was found almost exactly two years later, in September 2016, north of the HMS Erebus.

Both ships are in pristine condition despite resting beneath the sea for more than 170 years and the artifacts which remain have immense value.

In October, the United Kingdom said it would transfer ownership of the ships and their contents to Canada.

Earlier this month, the federal cabinet ordered the National Historic Sites of Canada be amended to add 57.8 square kilometres of seabed encompassing the HMS Terror.

‘‘An area of this size is required to prevent access and activities directed at the wreck, and to protect underwater historical resources related to the wreck,’‘ reads the order in council published last week.

‘‘The size of the area would protect any underwater debris and artifacts dispersed around the wreck, make it difficult for unauthorized individuals to approach the wreck, and facilitate monitoring of the site.’‘

A similar order was made for the sea bed around the HMS Erebus in 2015.

Nobody is currently allowed to visit the sites without permission. Not that getting there would be easy.

King William Island is more than 200 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle in Nunavut, and boasts just one, small settlement — the Inuit hamlet of Gjoa Haven — on its southeast edge.

The HMS Terror lies 24 metres beneath the surface of the water in Terror Bay. The HMS Erebus is 11 metres below the surface.

On the Parks Canada website dedicated to the wrecks, the ‘‘getting here’‘ tab paints an unappealing picture of making the trip.

It says while the region offers ‘‘spectacular scenery, wildlife and opportunities to experience Inuit culture’‘ it also comes with ‘‘a host of dangers’‘ including remoteness, limited access to help for anyone who runs into trouble, unpredictable river crossings, high winds, and polar bears.

‘‘You must be self-reliant and responsible for your own safety,’‘ the site says.

Inuit guardians were posted at both wreck sites throughout the ice-free season to protect them. The sites are also monitored with help from the RCMP, Department of National Defence, Transport Canada, the Canadian Space Agency, and the Canadian Coast Guard.

Longer term protection is in development for a permanent Inuit guardians program, and for the eventual ability of people to visit the sites.