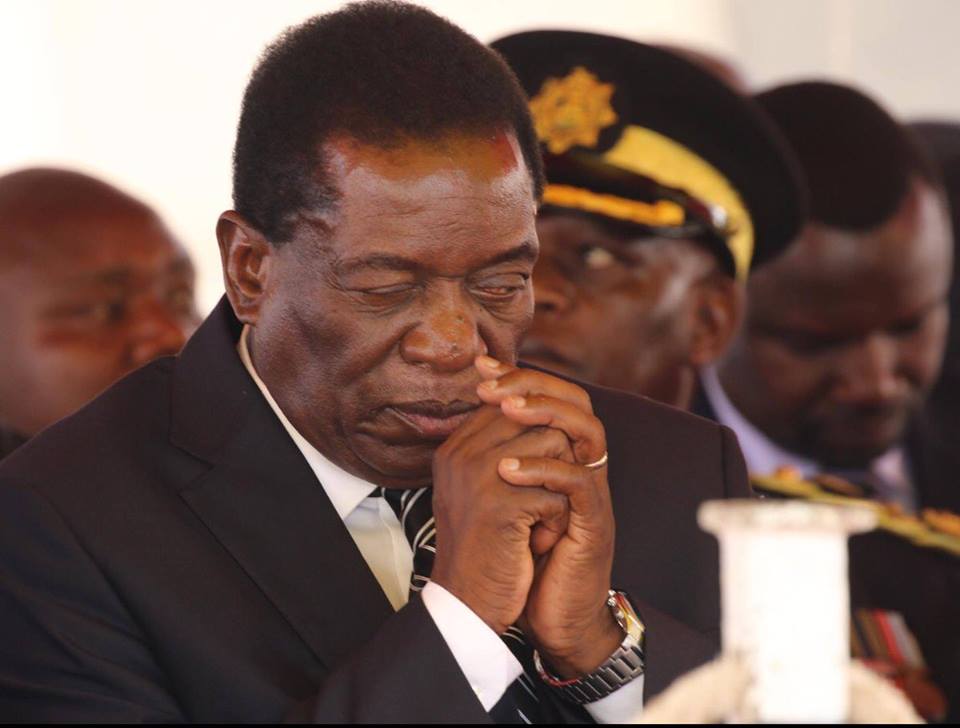

JOHANNESBURG — Emmerson Mnangagwa, elected Sunday as the new leader of Zimbabwe’s ruling political party and positioned to take over as the country’s leader, has engineered a remarkable comeback using skills he no doubt learned from his longtime mentor, President Robert Mugabe.

Mnangagwa served for decades as Mugabe’s enforcer — a role that gave him a reputation for being astute, ruthless and effective at manipulating the levers of power. Among the population, he is more feared than popular, but he has strategically fostered a loyal support base within the military and security forces.

A leading government figure since Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, he is so widely known as the Crocodile that his supporters are called Team Lacoste for the brand’s crocodile logo.

The 75-year-old “is smart and skilful, but will he be a panacea for Zimbabwe’s problems? Will he bring good governance and economic management? We’ll have to watch this space,” said Piers Pigou, southern Africa expert for the International Crisis Group.

Mugabe unwittingly set in motion the events that led to his own downfall, firing his vice-president on Nov. 6. Mnangagwa fled the country to avoid arrest while issuing a ringing statement saying he would return to lead Zimbabwe.

“Let us bury our differences and rebuild a new and prosperous Zimbabwe, a country that is tolerant to divergent views, a country that respects opinions of others, a country that does note isolate itself from the rest of the world because of one stubborn individual who believes he is entitled to rule this country until death,” he said in the Nov. 8 statement.

He has not been seen in public but is believed to be back in Zimbabwe.

For weeks, Mnangagwa had been publicly demonized by Mugabe and his wife. Grace, so he had time to prepare his strategy. Within days of the vice-president’s dismissal, his supporters in the military put Mugabe and his wife under house arrest.

When Mugabe refused to resign, a massive demonstration Saturday brought thousands of people into the streets of the capital, Harare. It was not a spontaneous uprising. Thousands of professionally produced posters praising Mnangagwa and the military had been printed ahead of time.

“It was not a last-minute operation,” Pigou said. “The demonstration was orchestrated.”

At the same time, Mnangagwa’s allies in the ruling ZANU-PF party lobbied for the removal of Mugabe as the party leader. At a Central Committee meeting Sunday, Mnangagwa was voted in as the new leader of the party, which had been led by Mugabe since 1977.

In an interview with The Associated Press years ago, Mnangagwa was terse and stone-faced, backing up his reputation for saying little but acting decisively. Party insiders say that he can be charming and has friends of all colours.

Mnangagwa joined the fight against white minority rule in Rhodesia while still a teen in the 1960s. In 1963, he received military training in Egypt and China. As one of the earliest guerrilla fighters against Ian Smith’s Rhodesian regime, he was captured, tortured and convicted of blowing up a locomotive in 1965.

Sentenced to death by hanging, he was found to be under 21, and his punishment was commuted to 10 years in prison. He was jailed with other prominent nationalists including Mugabe.

While imprisoned, Mnangagwa studied through a correspondence school. After his release in 1975, he went to Zambia, where he completed a law degree and started practicing. Soon he went to newly independent Marxist Mozambique, where he became Mugabe’s assistant and bodyguard. In 1979, he accompanied Mugabe to the Lancaster House talks in London that led to the end of Rhodesia and the birth of Zimbabwe.

“Our relationship has over the years blossomed beyond that of master and servant to father and son,” Mnangagwa wrote this month of his relationship with Mugabe.

When Zimbabwe achieved independence in 1980, Mnangagwa was appointed minister of security. He directed the merger of the Rhodesian army with Mugabe’s guerrilla forces and the forces of rival nationalist leader Joshua Nkomo. Ever since, he has kept close ties with the military and security.

In 1983, Mugabe launched a brutal campaign against Nkomo’s supporters that became known as the Matabeleland massacres for the deaths of 10,000 to 20,000 Ndebele people in Zimbabwe’s southern provinces.

Mnangagwa was widely blamed for planning the campaign of the army’s North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade on their deadly mission into the Matabeleland provinces. Mnangagwa denies this.

He is reputed to have amassed a considerable fortune and was named in a United Nations investigation into exploitation of mineral resources in Congo and has been active in making Harare a significant diamond trading centre.

In 2008, he was Mugabe’s election agent in balloting that was marked by violence and allegations of vote-rigging. He also helped broker the creation of a coalition government that brought in opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai as prime minister.

In recent years, Mnangagwa has promoted himself as an experienced leader who will bring stability to Zimbabwe. But his promises to return Zimbabwe to democracy and prosperity are viewed with skepticism by many experts.

“He has successfully managed a palace coup that leaves ZANU-PF and the military in charge. He’s been Mugabe’s bag man for decades,” said Zimbabwean author and commentator Peter Godwin. “I have low expectations about what he will achieve as president. I hope I will be proved wrong.”

Godwin, who has followed Mnangagwa for years, said he has little of Mugabe’s charisma or talent for public speaking.

Todd Moss, Africa expert for the Center for Global Development, also expressed reservations.

“Despite his claims to be a business-friendly reformer, Zimbabweans know Mnangagwa is the architect of the Matabeland massacres and that he abetted Mugabe’s looting of the country,” Moss said. “Mnangagwa is part of its sad past, not its future.”