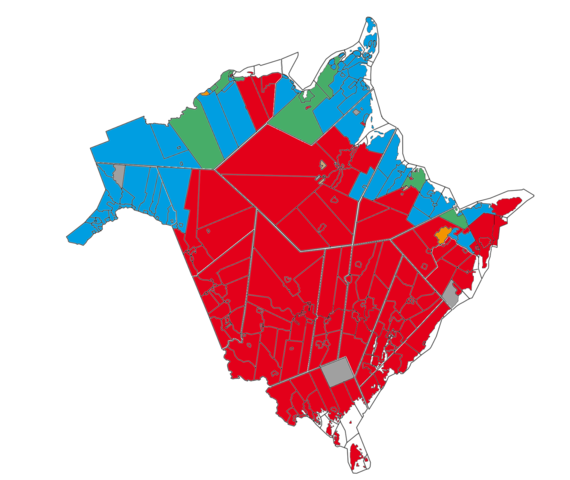

(Photo and caption from WIkipedia/Piotron)

FREDERICTON—Nearly 50 years after New Brunswick became Canada’s first officially bilingual province, the language debate continues to torment the province and generate heated arguments in both English and French.

Next month, the New Brunswick Court of Appeal will be asked whether school buses need to be segregated by language – meaning, it must decide whether the province needs two entirely separate school bus regimes, overlapping geographically but not linguistically.

“We have kids that will play in the same playground but can’t be transported to school on the same bus. There’s something seriously wrong with that. From a social level we just don’t agree with it,” said Kris Austin, leader of the People’s Alliance of New Brunswick, an opposition party which is seeking to intervene in the case.

It’s just the latest flashpoint in which the Acadian population fights to define its rights as broadly as possible, while some anglophones wonder about the costs of bilingualism in a cash-strapped province.

The province has witnessed debates over bilingual signs, bilingual staffing for paramedics, language obligations for municipalities, and even a much-discussed complaint—from the official languages commissioner—about a unilingual commissionaire temporarily assigned to the reception desk of a government building.

“I get Twitter feedback more than once a day attacking me. It’s a lot of rhetoric, it’s very vulgar and that doesn’t bring anything to the debate,” said Donald Arseneault, minister responsible for official languages.

About 31 per cent of New Brunswickers described themselves in 2011 as francophone; about 40 per cent of government employees are required to be bilingual.

During recent pre-budget hearings, a government committee heard from a number of people who said if the government wants to save money, it should look at what’s spent on official bilingualism.

Arseneault, who would not put a dollar figure on its cost, is quick to defend official bilingualism.

“Can you imagine what it would cost if we didn’t have it, in the sense of lost opportunities for the province? That’s what we need to focus on,” the minister said.

“We hear a lot of people trying to fearmonger. Nobody’s going to lose their job,” he said.

The school bus issue arose last spring when the provincial government discovered that students from French and English schools were travelling on the same buses in an area of southeastern New Brunswick. The school districts were ordered to stop the practice and added extra buses to comply.

At the time, Education Minister Serge Rousselle said the government’s obligation under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms is to provide separate French and English education systems, and that includes school buses.

The Charter guarantees separate educational institutions for French and English. As a result, the province has separate francophone and anglophone school boards.

NDP Leader Dominic Cardy said if the issue was that clear it wouldn’t need a review by the courts. He accused the government of ramping up linguistic tensions by claiming the buses were covered under the charter.

“I’m a defender of bilingualism in the province, but we’ve got to be able to sit down and talk about it rationally, talk about what works and what hasn’t, and figure out ways to make the system work better,” Cardy said in an interview.

Tensions go well beyond the one issue, and often comes back to cost—and opportunity.

Jake Stewart, a Progressive Conservative member, said everyone in the province should have the same right to learn both languages, but too many find themselves unable to get jobs because they aren’t bilingual. He introduced a motion in the provincial legislature in December calling for better second-language training in rural areas of the province.

Former Supreme Court of Canada justice Michel Bastarache said bilingualism became very polarized during public hearings that were launched after the release of a report he co-wrote on the issue in New Brunswick in 1982. He thinks memories of that debate continue to cloud discussion today.

“It brought out the very boisterous expressions of those who are from the extreme sides, and basically it didn’t work out at all. And I think everybody is fearful that this will happen again if we try to get a civilized debate on what we need to do to achieve a more efficient form of bilingualism,” Bastarache said.

Katherine d’Entremont, the province’s official languages commissioner, has been critical of the level of bilingualism on scales both large and small. She was critical last year of the city of Miramichi for not meeting its language obligations, and also launched an investigation after a commissionaire—who was temporarily assigned to the reception desk at a government building in Fredericton—was not able to serve her in French.

“It is surprising when we find that government institutions are still not able to provide basic services in both official languages. That is very difficult to explain. I think it speaks to the fact that it’s not given enough priority by the government of the day. It’s an ongoing issue,” she said.

D’Entremont stresses that the Official Languages Act is intended to ensure that government services are available in both languages and people can remain unilingual if they choose.

Still, she said there is a growing number of people who are bilingual.

“There have been great strides over the last few decades in terms of how many people are able to speak both official languages, due to a large extent to immersion which really started in the early 70s,” d’Entremont said.

Bastarache, though, said immersion has not been successful enough.

“There are still too many people in the majority of the population who are not fluently bilingual and we are not creating enough opportunity for those people to become bilingual. Even the school system with the immersion programs, I don’t think is a terrific success,” he said.

Despite nearly 50 years of official bilingualism in the province, both Bastarache and d’Entremont say it could be years before there’s full compliance and the squabbles subside.

“If one people feel cheated, feel diminished because they are not considered as equals, then you always have this social tension that never goes away unless you address the problem,” said Bastarache.