TORONTO – As Canadian kids prepare to head back to school, there’s a growing movement gaining traction across the country that involves students learning their lessons at home and doing their homework at school.

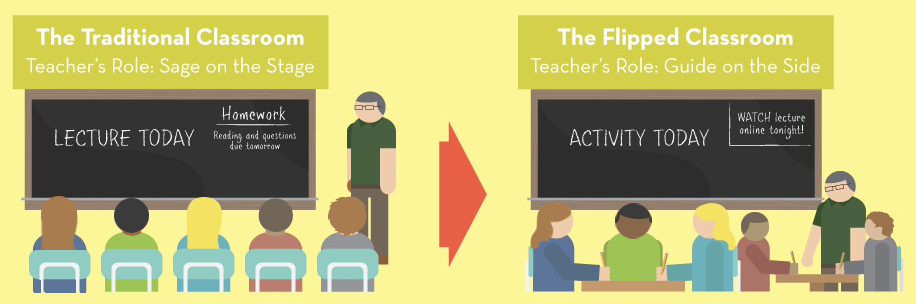

It’s called the “flipped classroom” – students watch an online video of a lesson as homework, and then work on problems during class time.

The method is becoming more prominent as technology in schools allows for videos to be accessed easily, either on custom-made sites, on YouTube or downloaded to a device.

A high school in Newmarket, Ont.

– Sir William Mulock Secondary School – is making the leap. Colloquially, they call it a “Bring-Your-Own-Device” school where every student has to have a laptop or tablet to be able to use the technology.

That technology has allowed teachers to flip their classrooms.

Donna Green, a math teacher at the school, flipped her Grade 10 academic math class in the second semester. She uses technology that captures video of her computer screen along with her voice as she progresses through a lesson.

The videos are usually shorter than in-class lectures, she says, because there are no disruptions.

“What I like about it is I am spending more time with the students than up at the board,” Green says.

“What I don’t like is when they are watching the video (at home) and they have an immediate question, there is no one to ask.”

Green tries to mitigate that problem by getting the students to write their questions down, and she goes over those questions first thing in class the next day.

Despite some of the drawbacks – most of the criticism has centred on the fact that low-income students may not have access to the technology required – Green and other teachers argue that flipped classrooms are better for the students.

There’s some evidence to back up their opinion. A high school in Michigan, one of the worst academic performers in the state, flipped every classroom in 2011, and saw failure rates decline significantly while graduation rates soared.

Green and her colleague, Amanda Belanger, surveyed their students in Newmarket through an online questionnaire about the new style. Two-thirds said they preferred it to the traditional “chalk-and-talk” method.

The results, Green says, show students like the ability to watch the videos at their own pace – they can pause, rewind and review them if they’re puzzled.

Then they apply what they’ve learned from the video lessons to problems that they work through in class.

“When we assigned homework before, the deeper problems were the stuff they weren’t finishing at home because they didn’t know how to do it,” she says. “Now they’re finishing that at school, and we can help because we’re around.”

Math and science are natural fits for the method, but Green’s colleague, Derrick Schellenberg, uses it in his English class sometimes too.

He employed it, for example, when teaching the 12 stages of the so-called quest pattern in mythology.

“They would watch the video ahead of time and then we would deconstruct the idea in class; then we would apply it to a film or short story or a book or a play,” he says.

An important facet to the flipped classroom, both Green and Schellenberg say, is asking questions at the end of class to ensure all the students understand the lessons and the subsequent in-class homework. The teachers then immediately compile and tabulate the responses electronically.

“What’s great is I’ve immediately got a spreadsheet with 30 students, and I can go through them quickly and I can find the students who didn’t get the question rather than wait for a test to find out who’s struggling,” Schellenberg says.

Donna Feledichuk, a University of Alberta professor who researches teaching methods, recently turned her attention to an economics class at the school that taught traditionally in one semester, then used the flipped method in the second semester – with the same content and the same instructor.

Feledichuk was trying to understand why international students in the class were lagging significantly behind their Canadian counterparts. In the flipped classroom, there was an overall increase of 11.4 per cent in the final grade compared to the traditional class.

As a side benefit, she notes, attendance increased to nearly 90 per cent from 65 per cent.

She says students can pick up the theory much easier via the flipped classroom.

“We get these big gaps in ability because some kids get it right away, but most students need more than one or two examples to understand a subject – many need more than seven,” she says.

“You don’t do that many in a traditional classroom, but you do in a flipped classroom. There seems to be a real benefit to students teaching this way.”