Filipinos in Canada, nearly 800,000-strong, are in many ways the best ambassadors for their country and exponents of Filipino culture in this part of the world. But nothing else speaks more eloquently of Philippine ancient and ethnic history than the famed Tecson collection, housed at the UBC’s Museum of Anthropology (MOA).

To Dr. Miguel and Julia Tecson, pioneer Filipino professionals in Canada, MOA was, and will always be their museum of choice for their extensive collection of over 350 archaeological objects, mostly from the Philippines. This treasured collection was turned over by the couple to MOA in 1987, in a selfless gesture to help future generations, Filipinos and Canadians alike, gain a deeper knowledge of their native country’s history and cultural heritage.

“People thought of MOA as a museum for First Nations art but in reality it has an extensive trove from other cultures as well, but nothing from the Philippines then,” says Dr. Tecson, former UBC professor of psychiatry.

At the renowned museum are over 500,000 anthropological artifacts from around the world and 40,000 ethnographic pieces.

The Tecson donation consists of four parts and forms the bulk of MOA’s Philippine collection.

The Filipino philanthropist identifies the four parts as the Archaeological and Ethnographic artifacts; Selected Library of Oriental Ceramics and Pottery; Collection of Antique Maps and Prints of the Philippines and Asia kept at the Rare Books and Special Collection at the Main Library of UBC; and the Julia Tecson Textile Collection which includes her precious wedding ensemble.

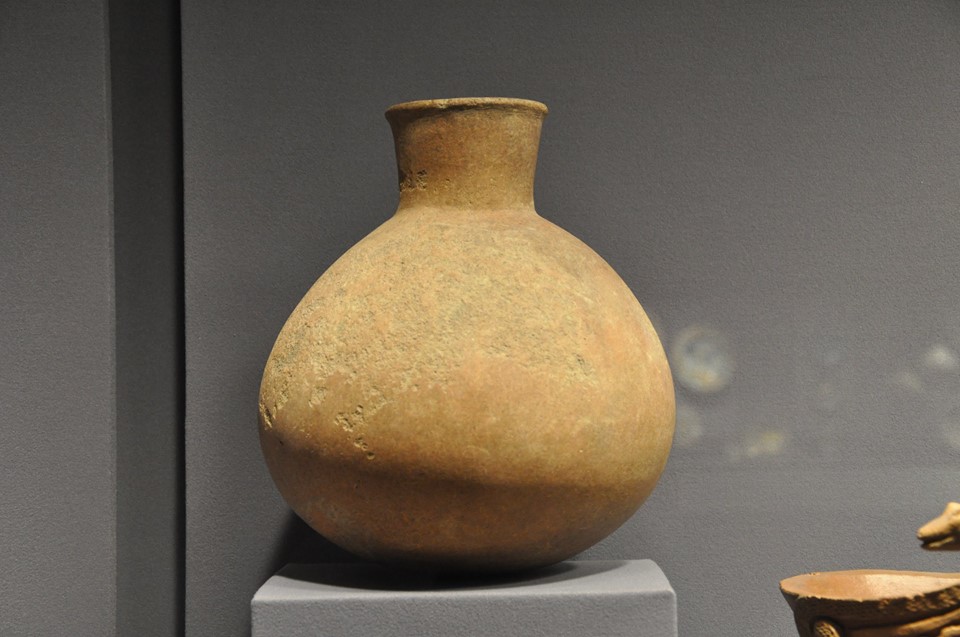

Dr. Tecson narrates that over the years, he and his wife amassed artifacts and memorabilia ranging from burial jars, jewelry, ancient pottery, carved religious images, reliefs, textiles, prints, maps and others. The students and friends who visited their residence at the University Endowment Lands were amazed at the collection, so the Tecsons decided to make this available to the next generation by donating them.

“The pieces are all heirlooms inherited from family, relatives and friends. All are genuine,” he says. “Some artifacts are from Philippine archaeologists like Henry Otley Beyer, the father of Philippine Anthropology. We lived next door to him and his son, Bill, gave me several burial jars (bulols),” adds Dr. Tecson, who holds the distinction of being the first Filipino licensed psychiatrist in British Columbia.

The couple purchased objects from indigenous tribes in Northern Luzon, Central Visayas and Mindanao. Other heirlooms were from commercial dealers who obtained them through excavations in the Philippines and Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand and South China. Still others were anthropological finds bought by the Tecson’s during numerous trips abroad.

The 84-year-old retired practitioner counts other influences who fired up his passion for revisiting the past. For one, his mother was a history major who started his love for reading at a young age. His father used to go on archaeological digs but was unable to unearth hidden treasures, Dr. Tecson adds.

His great grandfather, Pablo Tecson, a key figure in Philippine history, was a revolutionary captain who served as brigadier general in Gen. Gregorio del Pilar’s military command. Pablo was later elected first civil governor of Bulacan.

It was in Tecson’s ancestral house that the Pact of Biak-na-Bato was signed. This house, the largest in San Miguel, Bulacan, was often used to store old objects owned by the community.

Hence, the young Tecson grew up surrounded by life-sized paintings, baskets, weapons, antique furniture, ceramics, precious jars and other collectibles. In grade school, he started picking pottery. He intensified his acquisition after World War II, he recalls.

Dr. Tecson points out that he doesn’t have spectacular pieces. “Most of these are great representational pieces which are ideal for studies and research.”

His favorite relic is the cobalt blue jar with a lion head from Lapuyan, Zamboanga del Norte, which he says, comes with a touching love story.

He narrates, “The Sobanon clan (considered the equivalent of sultan) had been trading with the Chinese for hundreds of years before the Moros came to the Zamboanga peninsula.

During the Japanese era, the clan buried 100 of these precious jars in a pit. After the war, the Sobanons dug them out and traded them one by one to pay for their education, to get a wife or a carabao, or purchase a coconut plantation.

A friend of Dr. Tecson’s, an “ethical dealer” (one who dealt only in genuine pieces) had kept bringing him brown jars. Having collected several brown jars, Dr. Tecson one day requested a more colorful jar. The friend promised to get him one.

At that time, a young descendant of Sobanon wanted to study pharmacy in Manila so she traded the cobalt blue jar to Miguel’s friend. The two eventually fell in love, got married, had children, one of whom was sponsored by Dr. Tecson to pursue graduate studies at Simon Fraser University.

There is almost always an interesting story behind every piece forming part of the collection.

Yet there are other collections. The MOA collection is just one of the many the couple has contributed to learning institutions. When Julia was still alive, she donated $70,000-worth of ballet memorabilia to the Pacific Northwest Ballet in Seattle.

The Tecsons also donated three panels of wood-carvings done by the Fadul brothers, noted woodcarvers from Paete, Laguna. According to Dr. Tecson, these are probably at the UBC storage.

A mural by Carlos “Botong” Francisco, also carved in Paete, was given to a Catholic school in East Vancouver. “I don’t even remember which one,” Dr. Tecson says.

At MOA, however, is kept what is probably the most impressive one assembled by the Tecson couple over a lifetime. On May 24, the long-overdue launch will finally be held, alongside a fitting tribute to the famous donors and a special presentation as part of the month-long program of the Vancouver Asian Heritage Month Society.