VANCOUVER — Shaun Simpson has had a migraine headache for the past seven years.

His medical problems started with surgery to remove a piece of his skull that was pressing against his brain. The procedure left him with a spinal-fluid leak, which, in turn, fuels a near-constant headache.

For years, Simpson took a dozen or more Tylenol 3 pills a day, but they caused unpleasant side effects and weren’t completely effective.

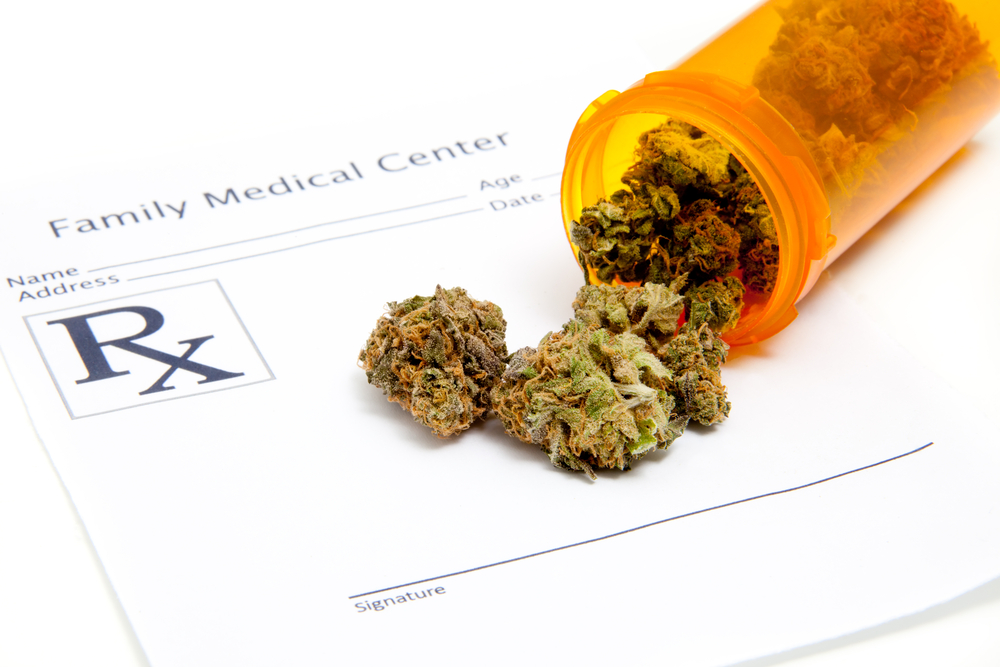

About two and a half years ago, he received a prescription for medical marijuana, which he ordered from Health Canada.

“I don’t feel like I’m drugged out or stoned from the Tylenol 3; I’m actually more active and social,” says Simpson, 34, who works as a photographer in the Maritimes.

“It’s really changed my life as far as day-to-day routine goes.”

Simpson is among tens of thousands of Canadians who have used medical marijuana legally since 2001, and, like many of those patients, he was forced earlier this year to adjust to a massive overhaul of the system.

The federal government implemented new rules prohibiting patients from growing their own pot and instead restricting production and sale to a new collection of licensed commercial operations.

But the system has been beset by complaints of low supply and high prices. Some commercial producers have long waiting lists and are plagued by frequent sellouts, and approvals for new operations to fill the gap have been slow.

Simpson initially signed up for Toronto-based Mettrum, but he said the company was often sold out of the strain he needed. He is now on the waiting list for OrganiGram, based in Moncton, N.B., and in the meantime he’s been using grey-market marijuana dispensaries.

Ottawa introduced the previous medical marijuana regime following a court decision in 2000 that ordered it to provide access to the drug.

About 38,000 patients received authorizations under that system, most of whom either chose to grow at home or asked someone else to grow it for them. Several thousand bought directly from Health Canada, which sold a single strain for $5 a gram.

The previous regime was repealed on March 31 of this year, leaving fledging commercial producers the only official option. However, a Federal Court judge issued an injunction that has allowed many patients to continue growing their own until a trial examining the updated rules in the new year.

There are currently 15 companies licensed to produce and sell medical marijuana; eight others are licensed to produce the drug but not to sell it.

Prospective suppliers must meet a list of strict conditions, including rigorous security requirements and measures to control odours.

Denis Arsenault, CEO of OrganiGram, says the regulations have mostly been working well. He said he understands the need for security and inspections.

“It’s been a very good experience; when they come in to do their inspections, it’s very clear they want us to succeed,” says Arsenault.

“Everybody is better off if a patient has access to their medicine, if there is a steady, regulated supply.”

OrganiGram has a wait list for new patients, but Arsenault says the company hopes to eliminate that soon.

Health Canada says about 13,700 patients were registered under the new system as of Oct. 31. That’s an increase from about 5,100 in April and almost 8,000 in June.

Patients with a doctor’s prescription place their orders directly with the licensed producer of their choice. The program is limited to dried marijuana; producers cannot sell other forms of pot, such as edible products or oils.

Costs range from as low as $2.50 per gram to as high as $15, depending on the producer and the strain, but most are between $8 and $10.

Those grams have added up: Health Canada says 1,400 kilograms _ or 1.4 million grams – were sold by licensed producers between Jan. 1 and Oct. 31.

There have only been three new licenses to sell marijuana issued since the summer, the most recent being MariCann, located in southern Ontario, which was added in early December.

As of Nov. 24, there were 301 applications still being assessed by Health Canada. Of those, 13 were awaiting a pre-license inspection — the final step before being approved.

Sundial Growers, which wants to produce medical marijuana near Airdrie, Alta., just north of Calgary, is in the queue.

Company president Stan Swiatek says he asked Health Canada for a final inspection in May. He has received a few requests for more information, but so far no one from the department has shown up and he has no idea when they will.

“It’s just sort of random — they arbitrarily decide which (application) to deal with,” says Swiatek, a former cucumber grower. “The reality is, we just have to sit and wait.”

In Nanaimo, B.C., Tilray says it’s currently operating at 20 per cent capacity because Health Canada hasn’t approved it to use all of its available space. A spokesman says the company has repeatedly asked Health Canada to inspect and approve the added production space, but there has been no response.

Health Canada says it does not track waiting lists at individual producers, though the department says there is adequate supply across the entire system. In October, for example, commercial growers produced 450 kilograms of marijuana, while only 240 kilograms were sold, the department says.

The federal government’s comments on the issue have largely been limited to pointing out marijuana is not an approved medical treatment. The government discourages anyone from consuming marijuana and points out it only allows medical cannabis because it was forced to by the courts.

Health Minister Rona Ambrose did not make herself available for an interview, but her office issued a written statement that repeated the government’s previous statements.

Neil Closner, CEO of MedReLeaf, based in Markham, Ont., says the government’s talking points appear to ignore the reality of patients, who say marijuana helps with a list of ailments.

“It certainly doesn’t help when messages are coming out from the government that it is not an approved drug and that it’s bad for you,” said Closner.

“There is mounting evidence — and it will only continue to grow — that this product is beneficial for many people.”

Producers are prohibited from making medical claims to patients. Last month, Health Canada sent most licensed growers letters ordering them to remove content from their websites beyond product names, price and cannabinoid content.

Closner says prohibiting producers from guiding consumers to particular strains based on their medical needs will only hurt patients.

“It’s our belief that patients need that information in order to make informed choices about which products to use,” he says.

Canada’s shift to a commercial market comes as federal politicians debate the larger issue of prohibition. Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau has been pilloried by the Conservatives for supporting legalization.

It also comes as several American jurisdictions establish recreational pot industries.

Voters in Alaska, Oregon and the District of Columbia approved ballot initiatives to legalize marijuana possession earlier this year, while Colorado and Washington state have already legalized the drug. Another 18 states have decriminalized possession of small amounts.

In addition, medical marijuana is available in 23 states.