Aeran Brent is tired of visitors asking about her store’s name or snapping pictures of the sign outside.

Unfortunately, that’s life for a small business owner whose shop—Isis Bridal and Formal—shares a name with ISIS, the acronym of a notorious Islamic militant group that the United States is fighting in Iraq and Syria.

“I’m just like, ‘Come on!”‘ she says. “I get what’s going on, but can you see it’s a store?”

Brent denies any connection with the other ISIS, which stands for the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, and says she wants to rename her store.

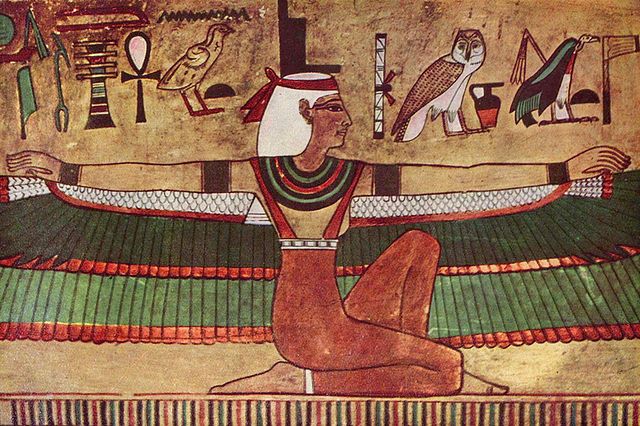

“Isis” is part of more than 270 product, service or business names among active federal trademarks, according to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. But businesses are not required to register their names, so it is difficult to say how many companies use “Isis,” which is also the name of an Egyptian and pagan goddess.

For those companies, the “Isis” name can be damaging. Branding experts say an unfortunate association with a name can scar a company’s reputation even if the connection is coincidental.

Take Isis Collections Inc., a New Jersey company that makes weaves, wigs and hair pieces. CEO Phillip Shin says stores have told him that customers will put his company’s products back on the shelf after noticing the Isis label. In the United Kingdom, he’s heard that competitors have joked at trade shows about his business being tied to terrorists.

“It’s so stressful,” Shin says, noting that he has spent 20 years building the company’s reputation. “I’ve lost all the benefit of the brand image.”

Shin, who named his company after the Egyptian goddess, started removing the Isis label from some packages. But he’s reluctant to give up on such an established brand. He says he wishes the U.S. and European media would stop referring to the militant group as ISIS.

Isis Collections has had no sales problems in South Korea, where the media only refers to the group as the Islamic State.

Another company, technology startup Isis Wallet, announced in September that it would change its name to Softcard. The joint venture involving AT&T, T-Mobile and Verizon Wireless launched late last year with an app that allows people to use their smartphones while checking out at a store to get discounts and use credit or loyalty cards.

By June, company leaders were thinking about rebranding to avoid confusion with the militant group, which had taken over large swaths of Iraq and later filmed the beheadings of some U.S. journalists and a British aid worker.

“However coincidental, we have no desire to share a name with this group, and our hearts go out to those affected by this violence,” CEO Michael Abbott said in a Sept. 3 blog post announcing the new name.

Softcard, which also picked its original name to reflect the Egyptian goddess, partners with major companies like American Express. The startup’s executives were worried about asking those partners to continue promoting a product named Isis.

“We didn’t want to put anybody in a bad situation,” says Cie Nicholson, senior vice-president of marketing.

Changing a brand or an established company name can be a costly and complex move. Just finding a memorable name can be hard because the best ideas are often taken or trademarked, says Allen Adamson, managing director of the branding firm Landor Associates.

“It’s not just have a pizza lunch and quickly come up with an alternative,” he says.

Softcard’s name change makes sense to Joseph Lewis, a partner with the law firm of Barnes & Thornburg who specializes in trademarks. He noted that the company is new and still building its image. With the old name, they would have had to take the extra step of explaining that they weren’t tied to the Islamic State group.

“Brands are owned by companies, but it’s all in the public’s mind and you can only control so much,” he says. “They can control how it is presented, but they can’t always control how it’s perceived.”

More established brands that don’t deal directly with consumers may not take as much of a hit. Isis Pharmaceuticals Inc. has no plans to change a brand it has built over 25 years. The California company develops drugs and then partners with other companies to sell them.

It doesn’t sell products directly to consumers, and its name doesn’t even appear on any of the products it helped develop.

So far, only a few investors have asked company officials about the name.

“We’ve been around for a while,” says D. Wade Walke, vice-president of corporate communications. “They can easily distinguish between us and a Middle Eastern terrorist group.”