OTTAWA — The key to unlocking the mystery of the missing Franklin Expedition came just days ago when a coast guard helicopter pilot spotted a dark U-shaped object in the Arctic snow the size of a man’s forearm.

The time-ravaged, orange-brown hunk of metal, vaguely in the shape of a tuning fork, bore the markings of the Royal Navy. It was a davit — part of a lifting mechanism, likely for a lifeboat, for one of the two lost Franklin ships.

On Tuesday, the davit sat on display in Parks Canada’s Ottawa laboratory, the only tangible link to one of the most enduring mysteries in both Arctic and Canadian history.

“That’s the clue that tells you: look here. That’s the flag,” said John Geiger, president of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

Geiger was with the search team that finally confirmed the discovery of one of two lost ships from Sir John Franklin’s doomed Arctic expedition.

The remarkable find completes one half of a puzzle that long ago captured the Victorian imagination and gave rise to many searches throughout the 19th century for Franklin and his crew.

The search team confirmed the discovery in the early morning hours of Sunday using a remotely operated underwater vehicle recently acquired by Parks Canada. They found the wreck 11 metres below the water’s surface.

It is not known yet whether the ship is HMS Erebus — the flagship on which Franklin himself was sailing, and is believed to have died — or HMS Terror.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who recently came close to the search area on his annual northern trip, could barely contain his delight Tuesday as he delivered news of the “great, historic” breakthrough.

“For more than a century, this has been a great Canadian story and mystery,” Harper said.

“I’d say it’s been the subject of scientists and historians and writers and singers. So I think we have a really important day in mapping together the history of our country.”

The Queen issued a statement Tuesday saying she was “greatly interested to learn of the discovery of one of the long-lost ships of Captain Sir John Franklin.”

“Prince Philip joins me in sending congratulations and good wishes to all those who played a part in this historic achievement,” she said.

The ship appears to be well-preserved. A sonar image projected at a media conference showed the ship five metres off the sea floor in the bow and four metres in the stern.

Ryan Harris, a senior underwater archeologist and one of the people leading the Parks Canada search, said the sonar image showed some of the deck structures are still intact, including the main mast, which was sheared off by the ice when the ship sank.

The contents of the ship are most likely in the same good condition, Harris added.

“You can see the tackle from the ship different riggings in the centre. This shows you how intact it really is,” added Andrew Campbell, a vice president at Parks Canada, as he screened underwater footage of the ship on a large flat screen television.

“The entire profile of this ship is there.”

Campbell said a combination of previous Inuit testimony, past modelling of ice patterns by the Canadian Ice Service, and the actual measurements of the two lost ships — they are both so similar they can’t yet be told apart — convinced the searchers that this was a Franklin ship.

When the search team telephoned Campbell in Ottawa early Sunday morning, “They cried, I cried. It was quite a moment.”

The discovery came a day after a team of archeologists found the tiny fragment from the expedition in the King William Island search area. Until Tuesday, those artifacts were the first ones found in modern times.

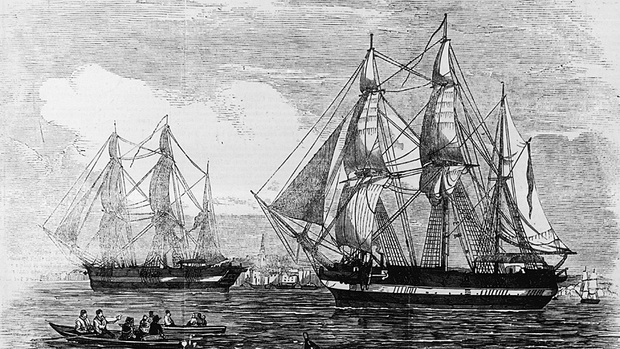

The two ships of the Franklin Expedition and their crews disappeared during an 1845 quest for the Northwest Passage.

They were the subject of many searches throughout the 19th century, but the mystery of exactly what happened to Franklin and his men has never been solved.

The expedition has been the subject of songs, poems and novels ever since.

The moment the ship was discovered this past weekend, said Geiger, “we were surrounded by ice — we were in a noose of ice — and so it was a real sense of connection, of immediate connection to Franklin and the men on those two ships.

“A few of us said a prayer to sailors lost at sea at that moment because we felt a real personal bond.”

Since 2008, Parks Canada has led six major searches for the lost Franklin ships. Four vessels led the search this summer — including the Canadian Coast Guard ship Sir Wilfrid Laurier, which launched the helicopter whose pilot made the pivotal davit sighting. It was joined by the Royal Canadian Navy’s HMCS Kingston and vessels from the Arctic Research Foundation and the One Ocean Expedition.

Officials recently said it was only a matter of time before the ships were found.

For now, they are keeping the exact location secret. Divers will begin exploring the ship’s remains on Wednesday.

Geiger said the site needs to be approached with great care and reverence. Over the years, “Franklinophiles, Franklin nuts all over the world” have mounted their own Arctic expeditions, and there have been cases of people scavenging human remains that they claimed belonged to the lost expedition.

Prior to this discovery, the only written document connected to the missing ships had been found on one single piece of paper, Geiger added.

“That’s it. The rest of the story has been told by human remains and a scatter of artifacts. To have this storehouse of information — it could be lost if not approached properly,” he said.

“Even in these initial passes, there’s incredible detail, incredible preservation. You’re going to have a wealth of information, objects, possibly some written records, if they were kept in water tight containers.”

The discovery itself was serendipitous, said Jody Thomas, deputy commissioner of operations for the Canadian Coast Guard.

The team was supposed to be searching in a more northern area, but the ice cover was too heavy, she said.

“The ice is very heavy this year. There is a myth that there is no ice in the Arctic, and that is exactly that, a myth. And so they were forced to go a little further south.”