MERIDA, Mexico—Jeremiah Tower plunged through the seafood aisles of this city’s central covered market, wrinkling his nose at a pile of limp grey sharks before his gaze landed on a pair of plump and glistening freshly caught octopus.

The man who once ran two of America’s most famous restaurants popped his first purchase into a monogrammed tote bag, then moved on to find the rest of lunch—bright orange chilies, brown beans, radishes, black blood sausage and a thick slab of Yucatecan pork belly fried crisp in its own fat.

Finally, he ate a late breakfast of cochinita pibil—the famous shredded pork slow-roasted in orange juice—and tender chunks of suckling pig topped with crackling pieces of fried skin.

“I’m 100 per cent satisfied and it cost me $3,” he declared. Making food like this is “all I ever tried to do,” he said.

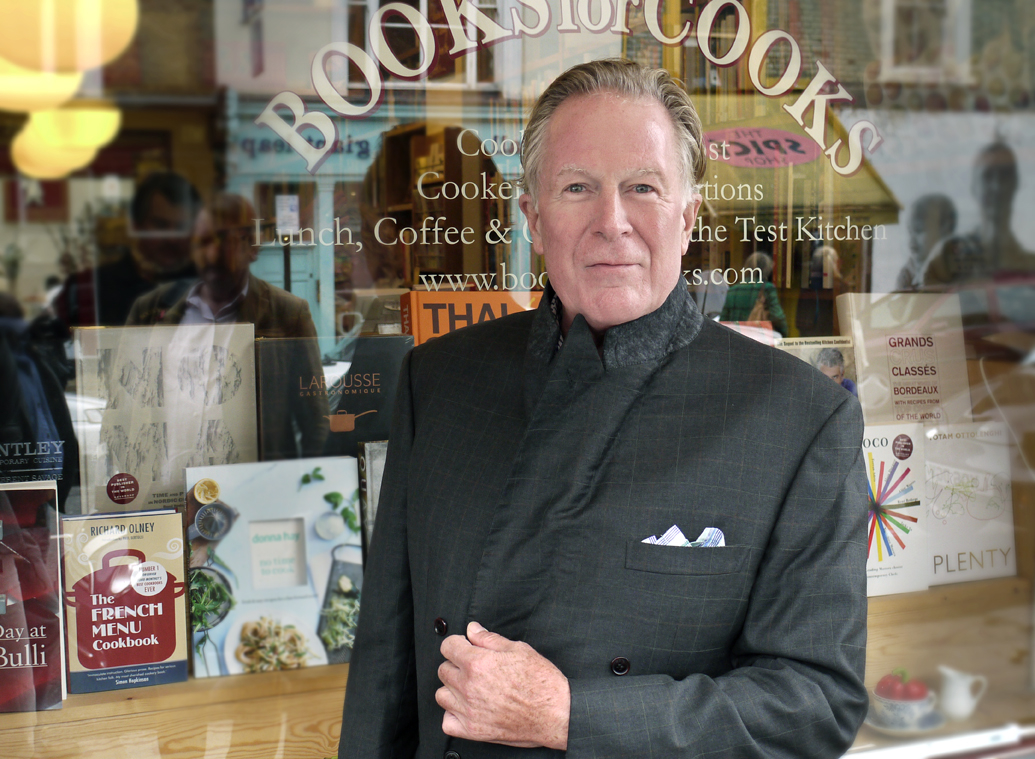

Tower made his name during the ‘70s at Alice Waters’ Chez Panisse, the famed Berkeley, California, restaurant that helped spawn a fresh-local renaissance in American cooking. He later became one of the first modern celebrity chefs at Stars, a San Francisco brasserie he says grossed $9 million a year serving cornmeal blinis and truffled lobster to Luciano Pavarotti, Barbra Streisand and other luminaries of ‘80s and ‘90s.

Now Tower’s third act is underway in the capital of Yucatan, the tropical Gulf Coast state whose richly spiced, fat-laden and pork-heavy Mayan cuisine has produced what Tower calls a handful of world-class dishes. It’s a very different life. The 71-year-old shops local markets in the mornings, visits taco stands for lunch, spends his afternoons working on a new book, an illustrated dictionary of the historical intersection of food and sex.

“Stars was the place to be and such an important restaurant in culinary history and then it dissipated and Jeremiah sort of disappeared off the scene,” said Dana Cowin, editor-in-chief of Food and Wine magazine. “There are not a lot of people like that. Jeremiah was one of the great founders, or if you want to say philosophers, of the idea of California cuisine.”

Tower acknowledges missing the glamor of days when he was one of America’s best-known chefs. And he regrets the missed opportunities to capitalize on fame, something today’s top chefs seem so adept at.

“When things are great, some people they don’t pay any attention. What I should have done? The list is so long,” he says. “I never thought about how to turn this into $40 million, unfortunately,” he says, gesturing at the remains of a lunch of braised octopus in black mole and pork belly on sauteed brown beans with chili-lime sauce and fresh radish salsa.

But he doesn’t regret leaving California. “There’s nothing worse than an old tired chef hanging around waiting for something to happen,” he says.

As Tower tells it, the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake was the first in a series of natural and man-made disasters that pushed him from San Francisco to New York to New Orleans to his new home in Mexico. The destruction in San Francisco’s Civic Center devastated business for Stars, which he said lost $9 million in four years after the quake.

He moved to Greenwich Village, but after 9-11 headed to New Orleans. He was scuba diving in Cozumel, Mexico, when Hurricane Katrina hit and destroyed most of his possessions. Tower stayed in Mexico and a few months later, he says, Hurricane Wilma destroyed most of what he had left.

The man who once owned an apartment in San Francisco, a house outside the city and a warehouse full of art and furniture, now can fit his possessions into a couple of suitcases. “I can move in four hours in a pickup.”

Before the global economic crash, Tower, who has an architecture degree from Harvard, bought, renovated and sold a series of colonial homes around central Merida. Now, when he’s not writing, he takes the bus to the Caribbean coast for days-long scuba diving trips, a post-restaurant life hobby he says has become a passion.

He said he doesn’t miss much about the days of Stars, where he turned the dining experience into theatre, once flew an employee to Paris to prove that the chicken there was better and, as he tells it, even put thousands of dollars of Veuve Clicquot Champagne on the curb because it wasn’t fresh enough for him.

The food world, of course, has moved on, though Tower still travels to eat and keep abreast of trends. He finds the current obsession with molecular gastronomy interesting, noting that the scientific techniques that allow chefs to create flavoured smokes and foams are reminiscent of the elaborate French cuisine that was revolutionized by his hero Auguste Escoffier during the 19th century.

And Tower’s star may be rising again. He’s embraced social media, is working with partners to develop a seasonal restaurant on a farm on Orcas Island, Washington, and Anthony Bourdain—who credits Tower with transforming the way Americans eat—is working on a documentary about him.

“He’s a hero of mine,” Bourdain says. “Jeremiah was a true innovator, an important original, and probably the first American chef anyone wanted to see in the dining room. He was an integral part of a power shift that has changed menus all over the world.”