LONDON — Britain’s fertility regulator says controversial techniques to create embryos from the DNA of three people “do not appear to be unsafe” even though no one has ever received the treatment, according to a new report released Tuesday.

The report based its conclusion largely on lab tests and some animal experiments and called for further experiments before patients are treated.

“Until a healthy baby is born, we cannot say 100 percent that these techniques are safe,” said Dr. Andy Greenfield, who chaired the expert panel behind the report.

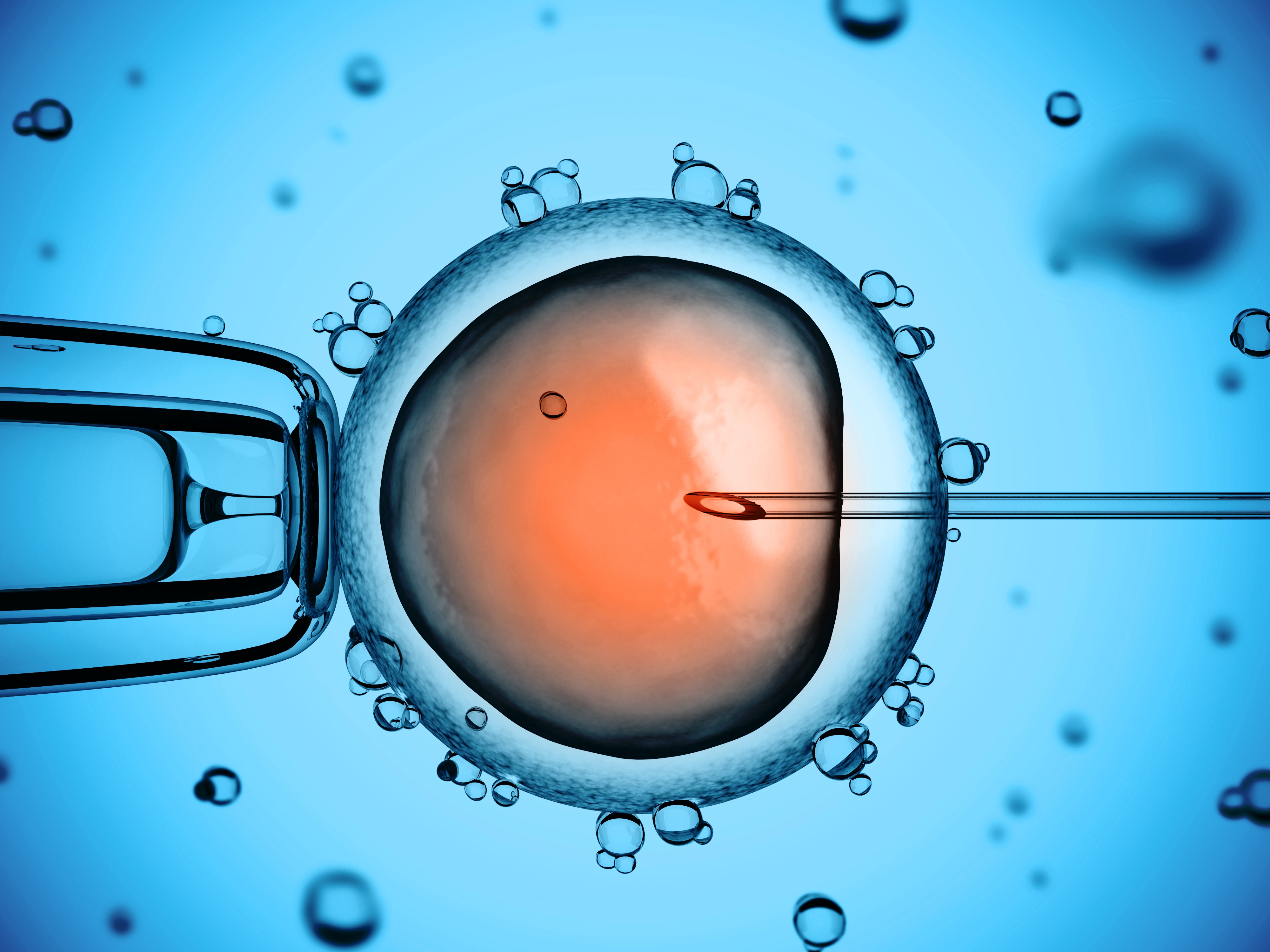

The techniques are meant to stop mothers from passing on potentially fatal genetic diseases to their babies and involve altering a human egg or embryo before transferring it into a woman. Such methods have only been allowed for research in a laboratory, but the U.K. department of health has said it hopes new legislation will be in place by the end of the year that allows treatment of patients.

If approved, Britain would become the first country in the world to allow embryos to be genetically modified this way.

Critics have described the research as unethical and warn the novel technology has unknown dangers.

“Safety is not a straightforward issue,” Greenfield said, comparing the ongoing debate to qualms about in vitro fertilization in the 1970s before the first test tube baby was born.

Marcy Darnovsky, of the Center for Genetics and Society in the U.S., warned that allowing embryos to be created this way might lead to a slippery slope and tempt scientists and parents to use the techniques to create designer babies with certain traits.

Experts say that if approved, these new methods would likely be used in about a dozen British women every year, who are known to have faulty mitochondria – the energy-producing structures outside a cell’s nucleus. Defects in the mitochondria’s genetic code can result in diseases such as muscular dystrophy, heart problems and mental retardation.

The techniques involve removing the nucleus DNA from the egg of a prospective mother and inserting it into a donor egg, where the nucleus DNA has been removed. That can be done either before or after fertilization.

The resulting embryo would end up with the nucleus DNA from its parents but the mitochondrial DNA from the donor. Scientists say the DNA from the donor egg amounts to less than 1 percent of the resulting embryo’s genes. But the change will be passed onto future generations, a major genetic modification that many scientists and ethicists have been loath to endorse.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration held a meeting to discuss the techniques and scientists warned it could take decades to determine if they are safe.