DELANO, Calif. – In California’s fertile Central Valley, immigrant workers pick produce sold worldwide. They’re mostly Spanish speakers who work long hours in the dirt and sun – not your typical crowd for a Hollywood movie premiere.

But this week, they were the guests of honour at a special screening of “Cesar Chavez,” the new biopic opening Friday. More than 1,000 farm workers sat in folding chairs outside the union hall where the first contracts were signed in 1970 between those who owned the fields and those who worked them. An inflatable movie screen stood upfront. The spirit of Cesar Chavez was everywhere.

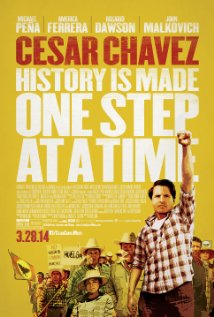

Directed by Mexico’s Diego Luna, “Cesar Chavez” follows the late civil rights leader from his first efforts to organize farm workers in 1962 to that historic 1970 signing. Before the contract, labourers worked the fields for pennies an hour and without breaks, bathrooms or shade. The union Chavez founded with fellow activist Dolores Huerta became the United Farm Workers, which continues to seek better wages and working conditions for field labourers two decades after Chavez’s death in 1993.

On Tuesday, Chartered buses brought screening guests from six Central California counties to The Forty Acres in Delano, Calif., the union’s original headquarters, now a National Historic Landmark. Some were veterans of the strikes and boycotts Chavez led in the 1960s; others struggle today to organize under conditions not unlike those he fought against. Many held red flags and wore T-shirts with the United Farm Workers logo and famous motto, “Si se puede!”

“This film is about you. It’s about the people who feed this country,” Luna told the crowd in Spanish. “It celebrates all those who today continue fighting.”

The Lionsgate release stars Michael Pena as Chavez, America Ferrera as his wife, Helen, and Rosario Dawson as Huerta. John Malkovich, also a producer of the film, plays a villain grape grower.

The Cesar Chavez Foundation, United Farm Workers and the studio sponsored the outdoor screening, which also included a barbecue dinner for all 1,200 guests. The special premiere, dubbed in Spanish for the occasion, concluded a pre-release promotional tour that stopped at the White House last week for a screening with President Obama, who adopted the union’s motto – translated, Yes, we can! – for his 2008 presidential campaign.

For Paul F. Chavez, one of Cesar Chavez’s eight children and head of his namesake foundation, the screening for farm workers was the most significant of all.

“It was good to hear the President’s comments … about the inspiration he’s taken from my father’s life. Then we were in Hollywood with a red carpet event, and that’s fun with all the movie stars. But this is really meaningful,” Paul Chavez said. “To come back where the work began, where so much history happened, then to be with people that work on a daily basis to put food on our table, it’s heartwarming.”

The Forty Acres is about two miles from where Cesar Chavez began his movement: The house where he lived with his family, the Filipino Hall where he announced his first fast, Delano High School where the farmworkers got support from Sen. Robert Kennedy, and the intersection where police tried to stop Chavez and 75 other strikers on their 250-mile march to Sacramento in 1966.

Josefina Flores, who lives in the foundation’s senior housing complex nearby, was there that day. At 84, she’s still involved with the union and hopes the biopic will educate and inspire.

“When they see how we suffered during that time, people can understand,” she said in Spanish. “And with the strikes and boycotts, they’ll see how they ought to organize as well to continue the pursuit of better (treatment)… It’s about respect and dignity for us and our children.”

Growers still intimidate immigrant farm workers, threatening to withhold pay if they don’t work faster, said 29-year-old Guadalupe Martinez, who works on a grape farm where the fight for contract representation has continued for more than a year. The gathering of workers and union members at the screening gave her hope.

“Here you can see the legacy Chavez left us,” she said in Spanish. “You can see there’s strength among us farm workers.”

Unfortunately, they weren’t able to see the end of the film that night. A sudden rainstorm swept through the drought-parched region, quenching thirsty crops but ending the outdoor screening early.

Boasting more than 50,000 members at its height in the 1970s, UFW represents about 4,500 workers today. Meanwhile, the non-profit Cesar Chavez Foundation builds and manages affordable housing for farm workers and seniors, provides educational services for young people and runs a nine-station Spanish-language radio network.

Paul Chavez said he hopes the film reminds farm workers their work is important and resonates with others who “care about justice and care about the future.”

“The fact is my father wasn’t 6-foot-2. He didn’t use big, fancy words. He didn’t come from a fancy, rich family. He never owned a car, never owned a house. He was a man that looks like a lot of people in this crowd tonight,” he said. “If people can see that a person like Cesar Chavez was able to make a difference, then our hope is that they’ll take a look at themselves and say, ‘Maybe there’s a little Cesar Chavez in me.’ And if that happens, then I think the movie’s been a big success.”