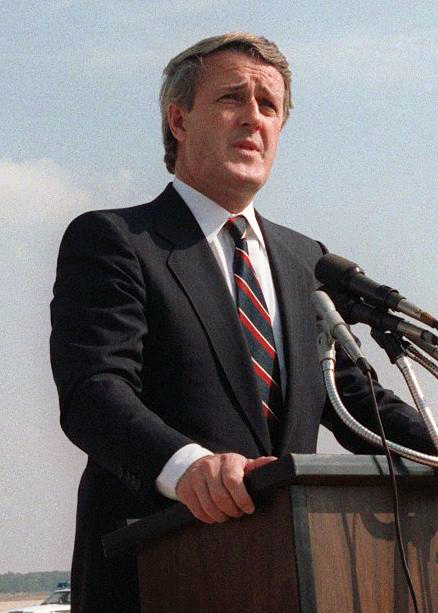

Wikipedia photo

OTTAWA – The night before the Meech Lake constitutional accord died, Brian Mulroney told his cabinet that recently departed minister Lucien Bouchard — who subsequently came within a hair of persuading Quebecers to secede — would have little influence in the post-Meech era, newly released records say.

Minutes of a June 22, 1990, cabinet meeting on Parliament Hill reveal the prime minister putting a brave face on the disintegration of the accord, aimed at winning Quebec’s endorsement of the Constitution after years of lingering resentment over significant 1982 reforms it did not embrace.

Bouchard had left cabinet the previous month as the accord — which would have recognized Quebec as a distinct society — began to unravel.

Once environment minister and Mulroney’s trusted Quebec lieutenant, Bouchard would go on to form the separatist Bloc Quebecois and to lead the Yes forces to near victory in the 1995 sovereignty referendum before taking over as premier.

Mulroney allowed that the post-Meech period would be “very unpredictable” for Canada. But he played down the influence of Bouchard, who exited cabinet after sending a congratulatory note to the Parti Quebecois to mark the 10th anniversary of the unsuccessful 1980 Quebec referendum.

Mulroney even suggested Bouchard was still something of an ally.

“He said that the former minister of the environment was not really a factor. The former minister was indeed on the side of the government and this would be to its advantage,” the minutes say.

“Mr. L. Bouchard would discover that he could not be independent and have sustained influence. He noted that Mr. (PQ Leader Jacques) Parizeau would prefer if Mr. Bouchard would stay in Ottawa.”

Bouchard did just that, founding the Bloc with a handful of similarly disaffected Conservative and Liberal MPs from Quebec. The upstart Bloc would win 54 of Quebec’s 75 seats in the 1993 election.

Mulroney was trying to soothe his shaken ministers on the eve of Meech’s failure, said Norman Spector, secretary to the cabinet for federal-provincial affairs at the time.

“He was bucking them up by denigrating Bouchard,” Spector said in an interview.

Jean Charest, then a Tory MP, also doubts Mulroney had any illusions about the repercussions of Bouchard’s resignation.

“He could see like everyone else that Bouchard had been able to capture an emotion in Quebec around this whole process that had gone sideways. Everyone understood that,” Charest said in an interview.

“But as a leader and as a prime minister, he was trying to reassure his troops.”

That said, Charest says it’s clear that Mulroney and others, including himself, misread Bouchard. He points out that Parizeau has since said he helped Bouchard plan his exit “way in advance” of his resignation, unbeknownst to anyone in Mulroney’s cabinet.

Ironically, Bouchard was instrumental in persuading Charest to chair a special committee tasked with recommending a companion resolution aimed at making Meech more palatable to hold-out provinces — the same committee Bouchard would later accuse of selling out the accord and use to justify resigning from cabinet.

Charest says he and his wife were having dinner with Bouchard and other friends when Bouchard suggested he should chair the special Meech committee.

“He was the one who asked me to chair it and at the time I was not enthusiastic about it … I was never naive about what was involved here.”

Later in the evening, Charest got a call from Mulroney “who asked me whether Lucien had raised this subject with me. Then I understood that the whole thing had been planned.”

The minutes suggest Bouchard said little in cabinet about Meech. In a notable exception, he is recorded at an April 3 meeting suggesting Charest’s travelling committee should “spend one or two days in Quebec, even at the risk of provoking the provincial government, because this could solidify some of the federal government’s shaky support in the province.”

Throughout his work on the committee, Charest says he met regularly with Bouchard to keep him informed about how things were evolving. He was “dumbfounded” to discover Bouchard planned to be out of the country when the committee’s report was to be tabled and pleaded with him to change his plans, to no avail.

Charest recalls trying “furiously” to reach Bouchard in Paris over the weekend before the report was tabled and sent him a copy “so that he could see the report before I signed off on it.”

“It was radio silence. He wouldn’t take my calls … I knew it was over,” he says. “We all felt betrayed because we had all been taken.”

Charest did not speak to Bouchard again until he became Quebec’s Liberal leader and joined the National Assembly in 1999, where Bouchard was by that time premier.

“After that, he and I had a good relationship and still do … We just don’t talk about these events.”

According to the minutes of a June 21 meeting, Joe Clark, external affairs minister at the time, argued that the country would need time to heal if Meech died and should not be plunged into another round of constitutional wrangling. Ironically, he became Mulroney’s constitutional affairs minister charged with negotiating the subsequent Charlottetown accord, which was roundly defeated in a nationwide referendum.

John Crosbie, then international trade minister, revealed in an interview that he was “very much against” Charlottetown, although as a cabinet minister, he supported it “because I couldn’t publicly say I thought it was a piece of crap.”

“It was too mealy-mouthed … It was a grab bag of stuff and I thought it was all disgusting.”

Follow @JimBronskill and @jmbryden on Twitter