As the world’s largest electorate goes to the polls in India, political parties are seeking to sway voters through popular culture, like film. Although cinema has long reflected and influenced the country’s political and social cultures, right now, Bollywood (and other Indian films) are a major boon to the current right-wing government.

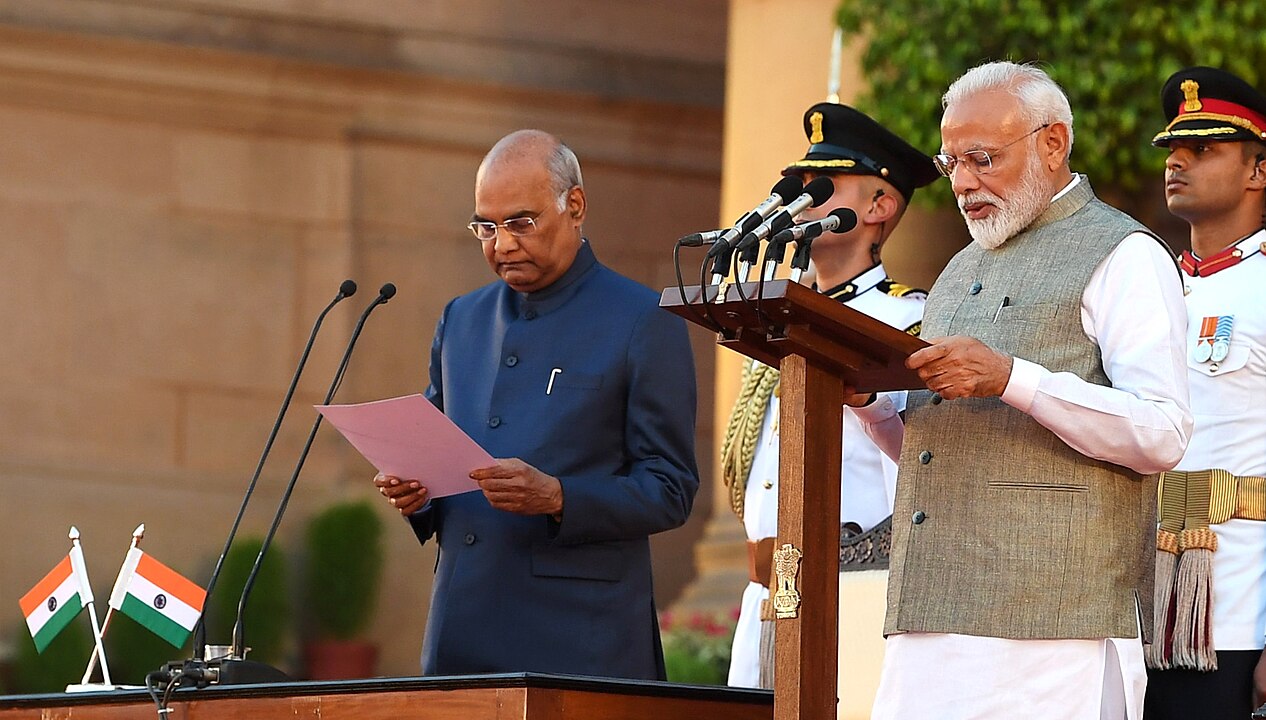

Led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is currently gunning for a third term in office.

First established as the political wing of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) — a paramilitary, volunteer organization — the BJP is one of two main political parties in India. The BJP believes that India, which is 80 per cent Hindu, is fundamentally a Hindu nation. Their platform has partly succeeded because of its widely appealing characterization of India as a post-colonial powerhouse. The opposition, The Indian National Congress, is a secular party. Last month, while campaigning, Prime Minister Modi delivered a speech that was widely criticized as Islamophobic.

On today’s Don’t Call Me Resilient podcast, political scientist Sikata Banerjee of the University of Victoria and cinema studies scholar Rakesh Sengupta of the University of Toronto, explain how cinema and social media operate to produce ideas that include “a vicious vocabulary of hate against minorities and dissenters” in India. All of which may be helping to sway voters.

“In Modi’s India, when people are asking these questions, why am I poor? Why am I feeling so worthless? The answer is always the Muslims,” says Banerjee. “The Muslims have taken away your wealth. They’re taking all the jobs…You see very clearly how Modi is getting people on board with this idea of the Hindu imagined community.”

It is partly this message of Islamophobia, mixed with a modern Hindu pride, that has infiltrated Bollywood, the largest film industry in the world churning out approximately 1,500-2,000 stories a year. These films have helped to circulate ideas of a newly imagined and highly appealing, strong and victorious India. That storytelling is in part bolstered by streaming platforms and social media like YouTube and WhatsApp, which have an even bigger reach than Bollywood films.

Some films, like last year’s breakout ‘Tollywood’ movie RRR, honoured at last year’s Oscars, retell history from the perspective of the current “victors.” Another recent example of a film accused of distorting history is Swatantra Veer Savarkar based on the life of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who developed the Hindu nationalist political ideology of Hindutva.

Sengupta at the University of Toronto says the relationship between cinema and state in India have always been historically intertwined. “You can always historically see a kind of reflection of the state of a particular time in the cinema of that time, he says. “Under the current regime of Hindu nationalism, we are witnessing more and more and more films being made on Hindu pride and Muslim violence.”

Polls in India opened on April 19 and undergoes seven phases until it closes on June 1, 2024. Results are announced on June 4.

Go deeper

(Sree 40)

Films discussed

- Awaara (1951) and Sree 420 (1955)

- Sholay (1975)

- The Chess Players or Shatranj Ke Khilari (1977)

- Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995)

- Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003)

- Tanhaji: The Unsung Warrior (2020)

- Tandav (2021)

- A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021)

- RRR (2022)

- All that Breathes (2023)

Listen and follow

You can listen to or follow Don’t Call Me Resilient on Apple Podcasts (transcripts available), Spotify, YouTube or wherever you listen to your favourite podcasts.

We’d love to hear from you, including any ideas for future episodes.

Join the Conversation on Instagram, X, LinkedIn and use #DontCallMeResilient.

Credits

This episode of ‘Don’t Call Me Resilient’ was co-produced by UBC student journalist, Marisa Sittheeamorn. Our team also includes: Ateqah Khaki (associate producer), Jennifer Moroz (consulting producer) and Krish Dineshkumar (sound designer).![]()

Vinita Srivastava, Host + Producer, Don’t Call Me Resilient, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.