Environment & Nature

Five options for restoring global biodiversity after the UN agreement

Less fishing means more fish at sea and higher catches for the remaining fleet with less effort. (Pexels photo)

To slow and reverse the fastest loss of Earth’s living things since the dinosaurs, almost 200 countries have signed an agreement in Montreal, Canada, promising to live in harmony with nature by 2050. The Kunming-Montreal agreement is not legally binding but it will require signatories to report their progress towards meeting targets such as the protection of 30% of Earth’s surface by 2030 and the restoration of degraded habitats.

Not everyone is happy with the settlement, or convinced enough has been promised to avert mass extinctions. Thankfully, research has revealed a lot about the best ways to revive and strengthen biodiversity – the variety of life forms, from microbes to whales, found on Earth.

Here are five suggestions:

1. Scrap subsidies

The first thing countries should do is stop paying for the destruction of ecosystems. The Montreal pact calls for reducing incentives for environmentally harmful practices by $US500 billion (£410 billion) each year by 2030.

Research published in 2020 showed that ending fuel and maintenance subsidies would reduce excess fishing. Less fishing means more fish at sea and higher catches for the remaining fleet with less effort. The world’s fisheries could cut emissions and become more profitable.

Scrapping policies which subsidise overexploitation in all sorts of industries – fisheries, agriculture, forestry, and of course, fossil fuels – are in many cases the lowest fruit to be picked in order to save biodiversity.

2. Protect the high seas

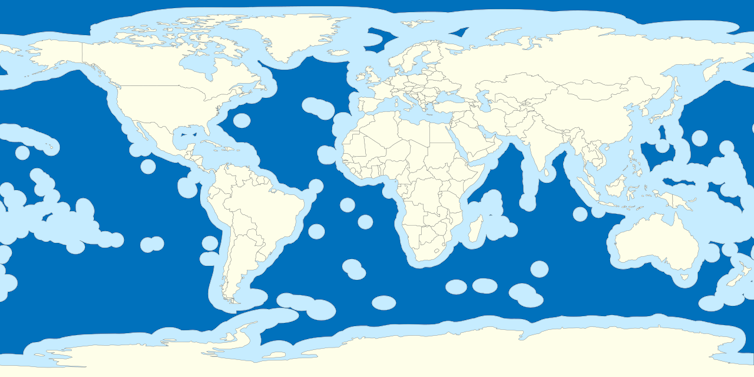

Almost half of the surface of the Earth is outside national jurisdiction. The high seas belong to no one.

B1mbo / wiki (data: VLIZ), CC BY-SA

In the twilight zone of the ocean, between 200 and 1,000 metres down, fish and krill migrate upwards to feed at night and downwards to digest and rest during the day. This is the ocean’s biological pump, which draws carbon from near the ocean’s surface to its depths, storing it far from the atmosphere and so reducing climate change.

The total mass of fish living in the open ocean is much greater than in overfished coastal seas. Though not exploited to any large extent yet, the high seas and the remote ocean around the Antarctic need binding international agreements to protect them and the important planetary function they serve, which ultimately benefits all life by helping maintain a stable climate.

3. Ban clear-cutting and bottom trawling

Certain methods of extracting natural resources, such as clear-cutting forests (chopping down all the trees) and bottom trawling (tugging a big fishing net close to the seafloor) devastate biodiversity and should be phased out.

Clear-cutting removes large quantities of living matter that will not be replenished before the forest has regenerated, which may take hundreds of years, particularly for forests in Earth’s higher latitudes. Many species which are adapted to live in fully grown forests are subsequently doomed by clear-cutting.

Bottom trawling catches fish and shellfish indiscriminately, disturbing or even eradicating animals which live on the seafloor, such as certain types of coral and oysters. It also throws plumes of sediment into the water above, emitting greenhouse gases which had been locked away. Seafloors that have been trawled continuously for a long time may appear to be devoid of life, or trivialised with fewer species and less complex ecosystems.

4. Empower indigenous land defenders

Indigenous people are the vanguard of many of the best-preserved ecosystems in the world. Their struggle to protect their land and waters and traditional ways of using ecosystems and biodiversity for livelihoods are often the primary reason such important environments still exist.

Such examples are found around the world, for example more primates are found on indigenous land than in surrounding areas.

5. No more production targets

Many management practices will have to change, since they are based on unrealistic assumptions. Fisheries, for instance, target a maximum sustainable yield (MSY), a concept developed in the mid 20th century which means taking the largest catch from a fish stock without diminishing the stock in the future. Something similar is also used in forestry, though it involves more economic considerations.

These models were heavily criticised in the subsequent decades for oversimplifying how nature works. For instance species often contain several local populations which live separately and reproduce only with each other, yet some of these “substocks” could still become overfished if just one production target was applied for all of them. However, the idea of a maximum sustainable yield has come back into fashion this century as a means to curtail overfishing.

Herring is a good example here. The species forms many different substocks across the North Atlantic, yet one maximum yield was adopted over vast areas. In the Baltic Sea for instance, Swedish fishing rights were given to the largest shipowners as a part of a neoliberal economic policy to achieve a more effective fishing fleet. Local stocks of herring are now declining, and with them local adaptations (genetic diversity) could eventually disappear.

Heading for more robust strategies than elusive optimal targets for extracting the most fish or trees while maintaining the stock or the forest may lead to a more resilient pathway regarding biodiversity and climate mitigation. It could involve lower fishing quotas, but also change from industrial fishing to more local fishing with smaller fishing vessels.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Henrik Svedäng, Researcher, Marine Ecology, Stockholm University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.