Canada News

To foster real change universities need to stand beside Black professors, not condemn them

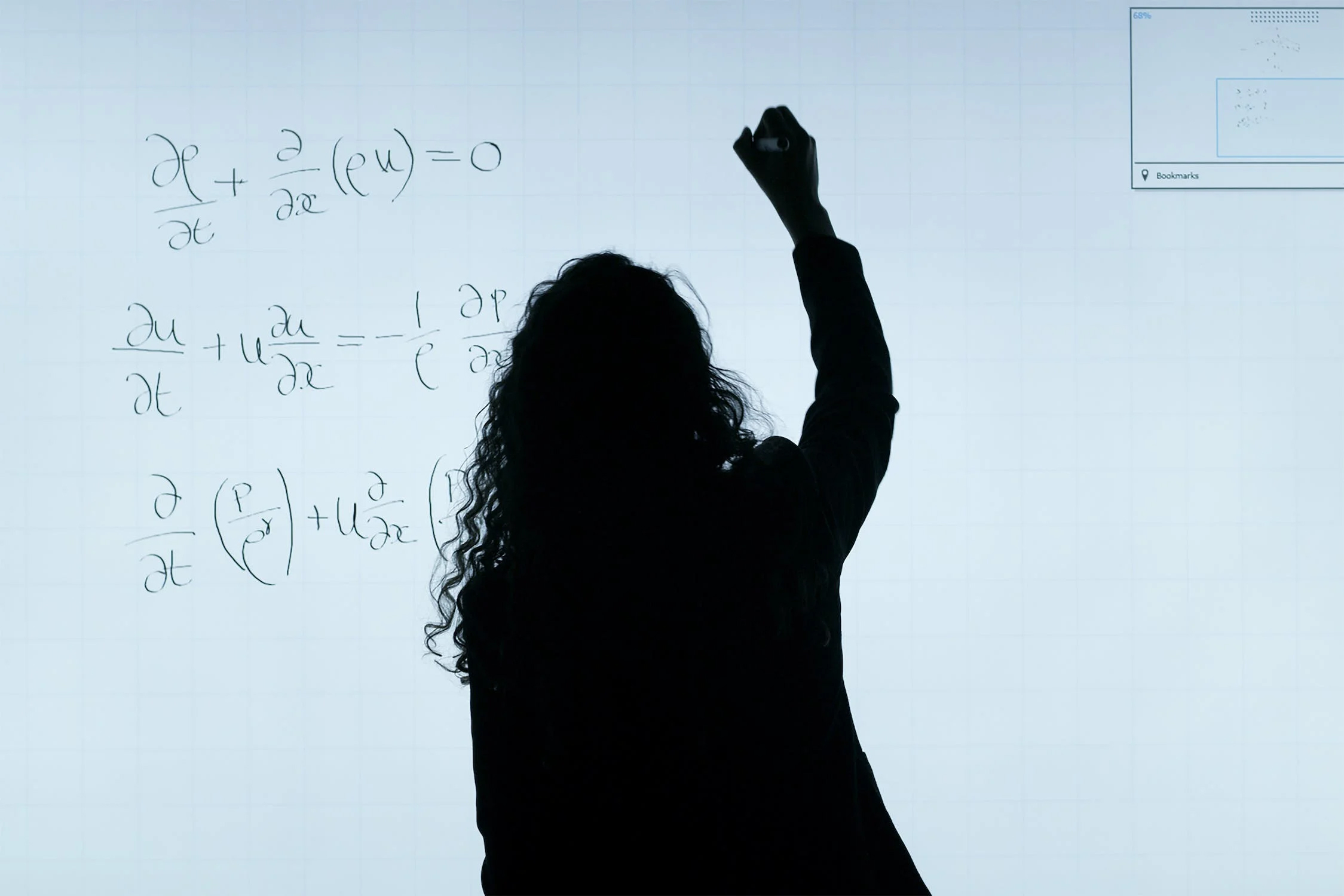

As universities prioritize the needs of corporate sponsors and economic interests, they jeopardize the ability of academic institutions to foster knowledge production and critical thinking. (Pexels photo)

The past couple of weeks have seen wall to wall coverage of Queen Elizabeth’s death. Many media outlets took to eulogizing the Queen with effusive praise of her service and duty. But not everyone saw her and the insitution she headed in the same light.

Many took to social media to discuss the Queen’s role in Britain’s imperial project, which includes profiting from and remaining silent on the violence of British colonialism and slavery. Uju Anya, a Nigerian linguistics researcher at Carnegie Mellon University was only one of the public figures who expressed her lack of pity for the Queen’s passing.

In a tweet, she wrote: “I heard the chief monarch of a thieving raping genocidal empire is finally dying. May her pain be excruciating.”

In another tweet removed by Twitter, she also wrote: “That wretched woman and her bloodthirsty throne have f***** generations of my ancestors on both sides of the family, and she supervised a government that sponsored the genocide my parents and siblings survived. May she die in agony.”

Twitter eventually deleted her other post, but not before it was met with backlash from many including Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. Bezos’s public admonition brought global attention — negative and positive — to Anya’s remarks. But in light of the criticism and harassment that she began to receive, her employer, Carnegie Mellon University, chose to denounce her comments.

Legacy of colonialism still resonates

“My experience of who she was, and the British government she supervised, is a very painful one,” Anya said in an interview. “The harm shaped my entire life and continues to be my story and that of the people she harmed — that her government harmed, that her kingdom harmed, however you want to frame it.”

“The genocide of the Biafra killed 3 million Igbo people,” she said, referring to the Nigerian Civil War, “and the British government wasn’t just in political support of the people who perpetrated this massacre; they directly funded it. They gave it political cover and legitimacy.”

As much as the university’s statement went on to laud “free expression,” their condemnation of their professor rings clear. The university’s refusal to defend Anya is emblematic of the lack of protection provided to Black women in academic institutions.

Supporting BIPOC faculty

The fact that Carnegie Mellon chose to distance itself from Anya’s comments is not surprising to scholars who have been tracking the increasing neoliberalization of higher education. It’s not a coincidence that Anya’s university chose to placate Jeff Bezos, one of its corporate donors.

According to scholar and cultural critic Henry Giroux, American universities have long been buckling under the weight of corporate culture. As universities prioritize the needs of corporate sponsors and economic interests, they jeopardize the ability of academic institutions to foster knowledge production and critical thinking.

“The ideals of higher education as a place to think,” Giroux says, “to promote critical dialogue and teach students to cultivate their ethical relation with others are viewed as a threat to neoliberal modes of governance. At the same time, education is seen by the apostles of market fundamentalism as a space for producing profits and educating a supine and fearful labor force that will exhibit the obedience demanded by the corporate order.”

On the front lines of the battle to keep education’s connection to democracy are those marginalized professors who continue to use their work to challenge that trend. And unfortunately, many Black professors find themselves at odds with their universities because of their academic work and their desire to speak truth to power.

The University of North Carolina denied Nikole Hannah-Jones tenure amid conservative backlash to her 1619 Project. Cornel West, famous for his work in African-American studies at Yale and Princeton, left Harvard because the university denied him tenure review. He suggested that Harvard’s decision may have stemmed from his pro-Palestinian stance. “I just want to make sure that each and every one of the universities have a fundamental commitment to intellectual freedom.”

In Canada, Aimé Avolonto, a French studies professor at York University launched a complaint with the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal because of the systemic anti-Black racism experienced on campus. He received backlash for speaking out. At other universities students have protested the racist language of certain white professors who at times receive support from their institutions.

Inclusion needs action

During the height of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, many universities circulated statements about their commitment to diversity and fostering anti-racist mindsets. Several Canadian post-secondary institutions have set out anti-racist principles that show their dedication to supporting Black inclusion.

But those statements mean very little unless universities actively create spaces for their BIPOC faculty, staff and students to speak and act for social change.

Words must be met with action. Universities must work to produce spaces of learning where social justice is lauded, not admonished. Where the needs of students and their democratic futures are put ahead of corporate sponsors.

Universities must look to their faculty not simply as workers but as respected social agents as higher education struggles to reclaim its connection with democracy.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.