Health

Vaccine hesitancy: Why ‘doing your own research’ doesn’t work, but reason alone won’t change minds

When the Green Bay Packers lost a playoff game to the San Francisco 49ers on Jan. 22, Twitter users were quick to roast Packers’ quarterback Aaron Rodgers’ anti-vaccination beliefs.

Rodgers misled his teammates about his vaccination status before testing positive for COVID-19 last November, revealing he was unvaccinated and stating that he was a critical thinker who had done his own research. Responses to Rodgers’ admission included Twitter mockery, but also fact-checking articles that addressed misinformation.

Earlier last fall, another celebrity’s COVID-19 vaccine comments drew even more attention, similarly divided. In September, when Nicki Minaj tweeted about her cousin in Trinidad, some ridiculed it, while others — including the White House — offered to put her in touch with medical experts who could correct her misconceptions.

Both types of response are equally futile.

Notice that both responses assume reason (and only reason) is responsible for human behaviour. Both responses assume a failure of reason; the only difference is the source of the failure.

The mockery assumes that some people lack the cognitive capacity or education to draw the correct inference from the data. The correction of misinformation assumes a lack of accurate information is preventing a rational conclusion.

Reason alone does not drive behaviour

As a cognitive neuroscientist who studies reasoning, I want to suggest that both of these responses make the same two mistakes.

The first mistake is a misunderstanding of the type of reasoning involved in making vaccine decisions. The second is more fundamental. It is based on an incomplete model of human behaviour.

The first mistake is obvious and can be quickly set aside. Most of us are not capable of “doing our own research” on COVID-19 vaccines. We do not have the training plus years of postdoctoral experience specializing in viruses and vaccines to seriously evaluate the primary literature, much less generate our own research. Even my family doctor, neurologist and cardiologist depend on the research produced by immunologists and vaccinologists.

The only thing most of us can do is follow the advice of specialists. “Doing our own research” simply amounts to making a decision on whom to believe. Do we believe the celebrities offering shocking and entertaining — but uncorroborated — opinions, the next-door neighbour, or the specialists at the Centers for Disease Control who have spent their lives studying viruses and vaccines?

This is an appropriate question to approach with reason. But our overly abstract notion of reason as detached from biology is a myth.

The tethered mind

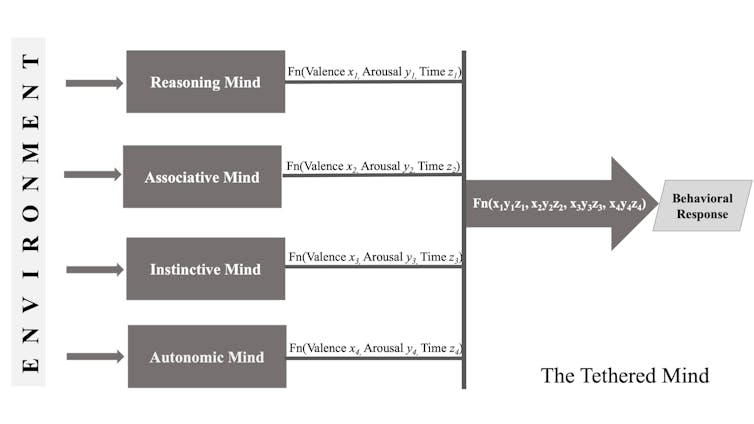

A more realistic conception of the human mind is one where we are reasoning creatures, but the reasoning system is interconnected — or tethered — to other biological systems that evolved earlier and function without our conscious input or awareness. Some examples are autonomic, instinctive and associative systems. This is a common-sense idea with deep implications developed in my book Reason and Less: Pursuing Food, Sex and Politics. What it means is that human behaviour is affected by all of these systems — not just reason, as is often assumed.

How these systems interact is guided by feelings: pleasure and displeasure. In some situations, the same action may be triggered by multiple systems. In other situations, different systems trigger different — even contradictory — actions. The overall response is guided by the principle of maximizing pleasure and minimizing displeasure, determined by combining the individual system responses

In-groups and out-groups

Deciding who to believe activates in-group/out-group systems. The in-group is always good and righteous. The out-group is of questionable virtue and held in lower regard. This bias is often regarded as based in belief or reason. If this were the case, we should be able to change it by changing beliefs, but we cannot.

I argue in my book that in-group bias is actually an instinct. Instinctive systems involve very different conceptual and neural mechanisms than reasoning systems. Instinctive behaviours, belonging to older brain systems, are automatically triggered and not easily changeable, certainly not by changing beliefs and desires.

So, if the real issue is who to believe — and we are subject to in-group/out-group instincts — and if we believe scientists belong to the in-group, this instinct will push us in the same direction as reason and enhance the pleasure/satisfaction associated with a decision based solely on reason.

If, however, scientists belong to the out-group, then the instinct pushes us in the opposite direction: they are evil and trying to deceive and harm us. In this case, if the pleasure we derive from exercising the in-group instinct is greater than that derived from other contributing forces, then we will be among the vaccine hesitant.

The issue is further complicated when the reason is used to intentionally sow doubt on the motives of experts to accentuate out-group differences. For example, “they don’t tell you how many people have died from the vaccine” or “if they can force you to have a vaccine under the guise of a so-called pandemic, what other medical procedures can they force upon you?”

This makes it even more difficult to overcome the instinctual bias. Any information to the contrary, no matter how clear or factual, will be less effective because it is pushing in the opposite direction to the instinct.

Notice that the same mechanisms and procedures are at play in both the vaccinated and the vaccine hesitant. The only difference is group membership. This is not a flaw in the system. This is how the tethered mind works.

Changing behaviour

Within this tethered mind model, how does one address vaccine hesitancy? Assuming that the vaccine hesitant lack reason or just need more information about vaccines and viruses is not correct or helpful. We need to factor in the non-reasoning systems that also drive behaviour and decisions.

According to tethered rationality, the following three strategies may be more successful:

Get the vaccine hesitant to expand their in-group to incorporate vaccine scientists. However, this is difficult because human in-group formation can be arbitrary and disjointed. For example, if the scientists are lumped with government, Big Pharma or other out-groups, assimilation into the in-group will be difficult for many.

Enable the vaccine hesitant to feel the severity of COVID-19 on a more visceral level, similar to the way anti-smoking campaigns from the ‘70s and ‘80s used graphic pictures of diseased lungs and emotional videos of dying cancer patients. These campaigns were more effective at changing behaviour than the earlier approach of printing the surgeon general’s health warning on cigarettes packs (appealing to reason alone).

Offer sufficient reward or penalty to tip the balance away from the pleasure associated with in-group membership.

Notice that none of these strategies targets reason. Reason is not the stumbling block. The stumbling block is the reality that reason is tethered to evolutionarily older systems that also have a say in behaviour. The first step in successfully changing a behaviour is having an accurate model of it.![]()

Vinod Goel, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.