Entertainment

The hidden maths behind our favourite Christmas films

What makes Christmas special to you? Festive experiences tend to include a series of selected elements that influence our sense of nostalgia, triggering good feelings, happy memories and emotional vulnerabilities.

Elements can be positive (your favourite carol) or negative (COVID), each adding to our personal experience. These elements form the “genetic make-up” of our individual Christmas experience, updated yearly as new elements materialise.

The same is true of our favourite festive films. Each hone seasonal elements to identify with the audience. Christmas films can be set against a snowy backdrop, relate to melancholy experiences or offer myriad enchanting yuletide moments.

Beloved Christmas films

To qualify for “Christmas movie” status, the story needs to have a meaningful use of Christmas and yes, that means Die Hard does qualify. Netflix’s Christmas Chronicles centres on a family who’ve lost their father, instantly playing on the melancholy of the situation. The writers use pockets of that element at different stages during the film, playing with our emotions.

Welcome to element philosophy. With Christmas elements, scriptwriters use them to tell their story, composers sprinkle scores full of sleighbells and producers use them to influence us to buy a ticket. “Element placement” dictates our emotional rollercoaster journey, and their positioning within a film’s duration is as crucial as the element itself.

Film writer Natalie Haynes explains that the best Christmas films put characters through the wringer – as in It’s A Wonderful Life, for example, where George Bailey decides to kill himself on Christmas Eve because he perceives his life to be a failure.

Haynes suggests Christmas movies rate love over money, family above gain, and add a little magic to the whole affair. Sometimes they don’t even have to be about Christmas – such as Meet Me in St Louis, starring Judy Garland.

But the Independent’s 20 greatest Christmas films 2020 suggest seasonal elements are important. As viewers we require familiarity and direction to enjoy and identify with a festive film. Screenwriting templates for dramatic structure exist, such as Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat, but where in the film’s timeline should the elements be placed?

How the golden ratio can be applied

The golden ratio is a mathematical proportion found in nature, such as the pattern of a shell or a sunflower. Mathematically, it’s a way of dividing a fixed length in two so that the ratio of the shorter portion to the longer portion equals the ratio of the longer portion to the entire length. Known as the golden or divine proportion, it has inspired artists throughout history to recreate it in painting, music, design, architecture.

Through seven years of research I discovered that the golden ratio can be made to fit anything if you look closely enough. It was originally suggested the pyramids were designed with the golden ratio in mind. But something of this magnitude will contain many patterns, including the golden ratio.

I wanted to find a system where people could utilise the golden ratio accurately as a modern-day model, as opposed to something imposed on a piece of art or a building long after the fact. I came up with the “Marley system” so creatives can use this time-based measuring device to match the golden ratio philosophy to performance, ending an age-old argument of analysis: “Is the golden ratio used?”

In May 2021, The Conversation published my article detailing how the golden ratio could explain the formula of hit musicals. Applying the Marley system to films highlights the key elements that intersect at the golden ratio points dictated by its duration.

Normally the golden ratio calculations are used as measurements of length of physical objects. The Marley system takes these measurements and applies them to seconds, minutes and hours of duration. These durations are then divided by 1.61803 (the number that represents the golden ratio) and a point in the film’s timeline is marked.

For example, the main golden ratio point of It’s A Wonderful life is 4,820 seconds into the film’s duration of 7,799 seconds, when George’s Uncle Billy loses the day’s business takings on Christmas Eve. A further golden ratio point is established by dividing the original golden ratio duration by 1.61803, and so on until we have 16 points in total.

Traditionally, the golden ratio demonstrates a sweet spot of aesthetic beauty in nature. In film, a standout moment that enforces our understanding or enhances our enjoyment, is classed as a sweet spot – such as the memorable scene in Love Actually when Hugh Grant, as prime minister, dances around Number 10 thinking he’s alone.

Once the golden ratio points of a film are calculated we analyse which plot elements (sweet spots) run significantly in parallel. As it’s Christmas, I wanted to test the concept to find if there are patterns evident in our favourite seasonal movies.

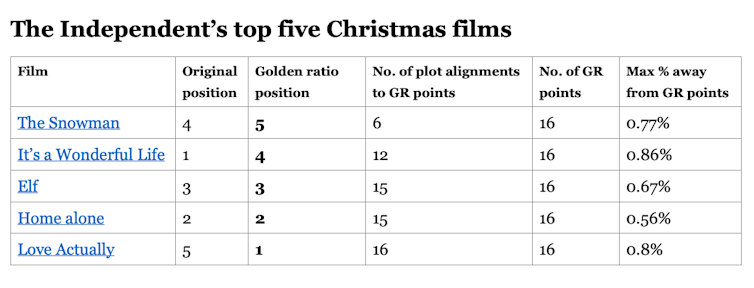

Using The Independent’s 2020 top five Christmas films, I employed the Marley system as an analytical tool to identify any alignment of element activity with golden ratio points in time throughout the duration of five Christmas popular films.

A pattern of significant plot elements was generated. These elements were cross referenced against each film’s plot, establishing their importance. The more relevant elements that manifested around these points increased the genre’s ranking as a golden ratio match.

The analysis reveals alignments between the golden ratio and the plot elements of each film, but the question is, do the alignments highlight the arc of the story?

This research uses the analytical approach to see what appears – in terms of the film’s plot – at golden ratio points, but does not imply the writers deliberately used the golden ratio as a catalyst for creation. It simply signifies interesting alignments. Ultimately, whether a movie is aesthetically pleasing is down to the filmmaker’s own creative genius.

Stephen Langston, Programme Leader for Performance, University of the West of Scotland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.