Health

Over-the-counter rapid antigen tests can help slow the spread of COVID-19 – here’s how to use them effectively

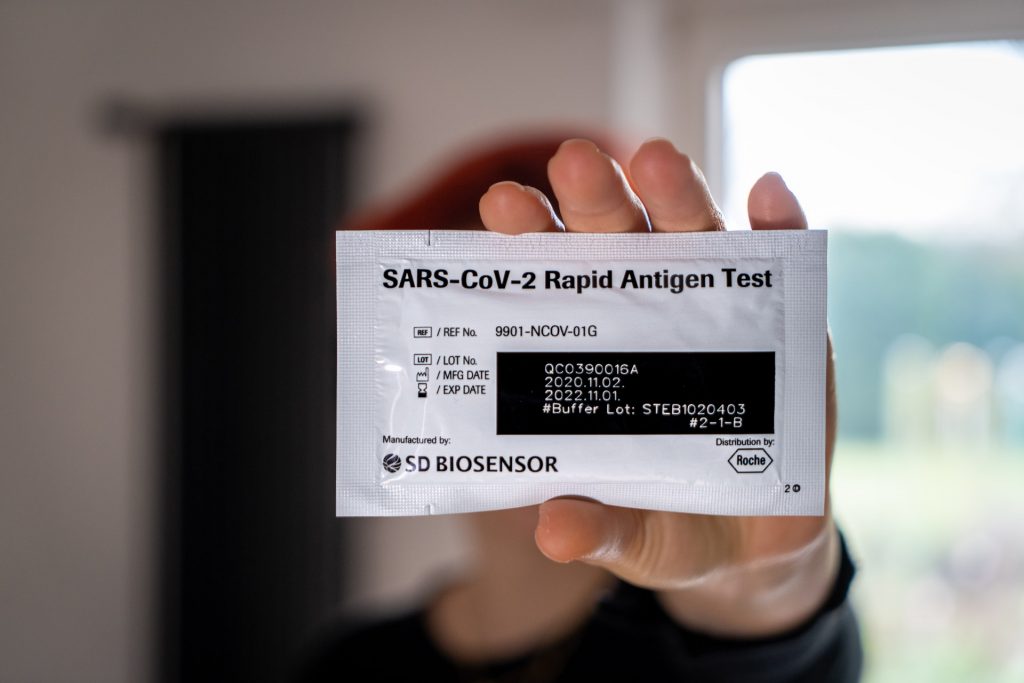

The rise of the highly transmissible delta variant around the U.S. has increased demand for rapid antigen COVID-19 tests that can be purchased from a pharmacy without a prescription, used at home, school or work and that give results in 15 minutes.

On Sept. 9, 2021, the White House announced several initiatives to improve access to rapid antigen tests: It will use the Defense Production Act to boost the production of tests, require retailers to sell rapid tests at cost, distribute free rapid tests to community health centers and food banks and expand free testing in pharmacies.

Rapid antigen testing makes it much easier to get tested for COVID-19, which helps detect infectious cases before they spread. But many people are still unsure of how best to use these tests and whether they are accurate enough to be useful.

There are several FDA-approved rapid tests on the market including Abbott BinaxNow, Ellume and Quidel QuickVue. These cost as little as $7-12 each and can be used to test adults and children aged 2 and up, regardless of whether they have symptoms.

Rapid antigen tests have a big advantage over lab-based PCR testing in terms of speed and convenience. Getting results in 15 minutes rather than waiting a day or more for PCR test results means it’s possible to identify COVID-19 cases right away and take precautions to prevent transmission. Having rapid testing available over-the-counter means that a lot more people will get tested since the test is easy to perform and far more convenient than PCR testing. So rapid tests can catch a lot more COVID-19 cases overall than relying only on PCR testing.

As a health economist who studies public health policy to combat infectious disease epidemics, I know that making COVID-19 testing accessible, accurate and fast is critical to slowing transmission of the virus and helping everyone resume normal activities safely.

How accurate are rapid antigen tests?

Two types of rapid tests are used for detecting an active COVID-19 infection: rapid antigen tests that detect viral proteins using a paper strip and rapid molecular tests – including PCR – that detect viral genetic material using a medical device.

It’s important to remember that rapid antigen tests serve a different purpose than PCR testing, which is considered the gold standard even though it isn’t 100% accurate. Rapid tests are designed to identify cases with a high enough viral load in the nasal passage to be transmissible – not to diagnose all COVID-19 cases. The Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test may only detect 85% of the positive cases detected by PCR tests. But the key is that published studies found that they detect over 93% of cases that pose a transmission risk, which is what matters most for getting the pandemic under control. Ellume correctly identifies 95% of all positive cases, and Quidel QuickVue accurately identifies 85%. All three tests correctly identify upwards of 97% of all negative cases, regardless of symptoms.

How should rapid tests be used?

Rapid antigen testing can be used in three ways to slow transmission. First, people can perform a rapid test when there is a suspected or known COVID-19 exposure. Second, rapid testing can provide an extra precaution before any activity with a higher risk of transmission, such as gatherings or travel. Third, it’s also possible to test on a regular basis – weekly, for instance, if enough tests are available – to catch cases that otherwise might go undetected.

It’s important to have a plan for what to do based on the test results. If you get a positive result, immediately take precautions to slow transmission such as self-isolating, letting close contacts know about the test result and reporting the case to health authorities. Less than 3% of positive results are false positives, but a second rapid test the following day or a PCR test can provide further confirmation if needed.

If you get a negative result from a rapid test, it means you are currently very unlikely to be infectious. A viral load that is too low to be detected by rapid antigen tests is almost surely too low to be transmissible. But it’s important not to let your guard down completely. The tests don’t detect 100% of infectious cases, so it’s possible for a small number to evade detection or for some cases to become infectious within hours after the test. For this reason, it may be a good idea to maintain other precautions. And, if you have symptoms or a known exposure, it’s a good idea to do a follow-up rapid antigen or PCR test just in case the first test was a false negative.

Think of the rapid antigen test as a snapshot in time: A negative test doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t have COVID-19. COVID-19 is most transmissible when the viral load peaks, which is estimated to be within a week after infection. Those who are infected but who take a rapid test before or after the viral load peak will get a negative rapid test result – meaning that even though they are infected, they are not currently infectious. One way to reduce the risk of false negatives is with “serial testing,” where a second rapid test is performed 24-36 hours later to help catch any infectious cases that were missed with the first test.

Will the new initiatives be enough?

The White House initiatives to increase access to rapid testing are a critical step towards curbing case numbers. But one free test per person isn’t sufficient to help people resume normal activities safely. Authorizing additional inexpensive rapid tests through the Food and Drug Administration would further expand supply and reduce prices.

Making the COVID-19 vaccine free and easily accessible brought cases down quickly in the spring of 2021. Putting frequent rapid testing within reach for all could do the same now.

[The Conversation’s most important coronavirus headlines, weekly in a science newsletter]![]()

Zoë McLaren, Associate Professor of Public Policy, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.