Lifestyle

When life gives you lemons … 4 Stoic tips for getting through lockdown from Epictetus

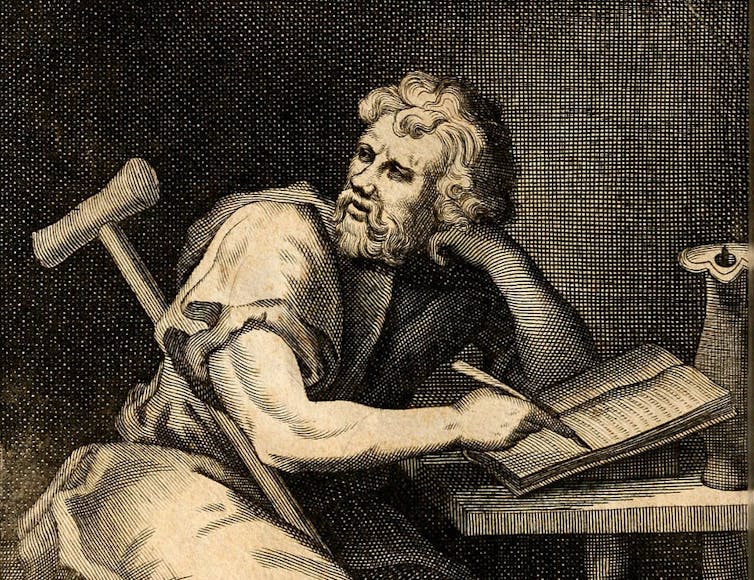

Born into slavery, then crippled by his master and exiled by the Emperor Domitian, Epictetus (c.60-135 CE) has become arguably the central figure in today’s global revival of Stoicism.

A straight-talking advocate of the idea philosophy should help people flourish even in hard times, Epictetus has much to offer as we wrestle with pandemic lockdowns and uncertainty. Here are four tips from perhaps the most stoic of the Stoics:

1. Don’t worry about things we can’t control

The start of Epictetus’ Enchiridion handbook lays out his famous “dichotomy of control”:

Of things some are depend upon us, and others do not. In our power are opinion, impulse, desire, aversion. Not in our power are the body, property, reputation, offices, and in a word, whatever are not our own acts.

It’s an idea that echoes today in the Serenity Prayer of 12-step recovery programs.

If we worry about things we can’t change, Epictetus continues, we are wasting our energies. If we imagine that we can control the past or future — or even pandemics — we are setting ourselves up for disappointment.

But we can think and act, and do our best to respond to situations with courage, justice, and moderation.

Today’s citizens in lockdown can’t control whether (or when) restrictions are lifted. We can all however wear masks, social distance, get vaccinated as soon as possible, and continue working, exercising and educating our kids as best we can.

2. Prepare for the worst, hope for the best

Like other Stoics, Epictetus observes people are most prone to being disturbed by events which take them by surprise. By premeditating the worst case scenario, and imaginatively working through how we could respond in advance, we can lessen our vulnerability.

If this “premeditation of evils” sounds too frightening, “begin from little things”, Epictetus advises:

Is the oil spilled? Is a little wine stolen? Say on the occasion, at such price is sold freedom from being upset; at such price is sold tranquillity, but nothing is got for nothing.

While the preparation can be confronting, Epictetus suggests that being grieved or angered by things we have no say over, like a sudden lockdown extension, is far worse. “Premeditated is prepared”, he tells us. If things go better than we prepare for, all the better.

3. Contextualise and ‘other-ise’

When we’re under duress, Epictetus observes, we often feel as if what we are experiencing is unprecedented. No one else can understand. But it helps to remember that few experiences, even during a pandemic, are unprecedented.

We are in the second year of COVID. But the world wars lasted four and six years. This is a pandemic, yet other generations have experienced plagues (or the Spanish flu) in which grievous losses were also sustained. Those who survived were able to rebuild. So will we.

It can also help, Epictetus suggests, to “step back” and assess our experience as if it was happening to somebody else:

For example, when a friend’s child breaks a cup it is easy for us to say, ‘That is in the nature of cups and of children.’ [But] when you realise that situation is true of you, it is easy for you to say that same thing to yourself when a child breaks your cup …

So, when we are inclined to despair in difficulties “we ought to remember how we feel when we hear of the same misfortune befalling others”. By looking at ourselves as if we were an other, we can apply the same support and encouragement to ourselves.

Read more: Why philosophers say solitude can be helpful (even if you didn’t choose it)

4. Slow down, make sure

Epictetus, echoing Socrates, says that any unexamined idea is not worth having. In life, we can easily leap between ideas in ways which lead us to false beliefs. Epictetus writes:

These reasons do not cohere: I am richer than you, therefore I am better than you; I am more eloquent than you, therefore I am better than you. On the contrary these reasons cohere: I am richer than you, therefore my possessions are greater than yours: I am more eloquent than you, therefore my speech is superior to yours.

Read more: Guide to the Classics: how Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations can help us in a time of pandemic

It’s easy to add a lot of avoidable, habitual, evaluative judgements to what we know and experience. Often, these add-ons introduce assumptions which aren’t based on adequate information. These lead us to react excessively or poorly.

Epictetus recommends we slow our roll and our “judginess” down, especially when it comes to condemning others:

Somebody is hasty about bathing; don’t say that he bathes badly, but that he is hasty about bathing. […] For until you have decided what judgement prompts him, how do you know that what he is doing is bad?

In the age of swarming internet conspiracies on social media, this fourth piece of old Epictetan advice is new again.

When presented with allegations of nefarious or appalling conduct by fellow citizens, Epictetus recommends we ask: do I know that that is true? Do I have enough information to be sure?

Such self-examination stops us from becoming enraged on the basis of fictions — let alone spreading misinformation which provokes or enrages others. If enough people do that, we could collectively avoid many future difficulties.

Matthew Sharpe, Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.